Children's Rights Thesis Corner

In this section we publish theses written by Maastricht University students on children's rights. Students write a blog post related to their research. At the bottom of the blog you can download their complete thesis.

29 Feb 2024 - By Kristin Melander

When I think of climate change, I don’t just see a daunting crisis; I see a ticking clock, a race against time that we cannot afford to lose. And in this race, I see the faces of children - the ones who stand to inherit the world we are shaping today.

It’s not difficult to feel a sense of powerlessness in the face of the climate debate and the decisions made by world leaders. Many of us can feel an overwhelming sense of frustration and helplessness. The increase of the climate problem can leave us feeling paralysed, making us question if our efforts make any difference at all.

Yet, amidst this despair, there is still a bit of hope - the unwavering determination of young people who refuse to surrender in this fight. Labelled rightly as a children’s rights crisis, we’ve witnessed youth-led climate strikes such as Fridays for Future. Students across the globe left their classrooms, demanding immediate action from governments. These passionate activists, often not old enough to vote, are proving that age is not a barrier to making a significant impact and that they are willing to stand up for their own future.

It’s their vulnerability, motivation and unyielding commitment that motivated me delve into the complex issue of climate change through the lens of children’s rights. My hope: to create a game plan that empowers children to stand for their claim to protection against climate change.

One aspect that was particularly important to me was that children themselves could potentially follow this framework and exert their claim to protection. In doing so, I wanted to acknowledge their capacity of not just being passive victims of climate change but active agents of change, empowering them to shape their own destiny and the destiny of our planet.

Furthermore, I made a deliberate choice to centre my research on present harm rather than building an argument solely for the benefit for future generations. The reason is simple yet profound: harm is happening right now. It is a current reality that demands immediate attention.

In the following blogpost, I navigate through the legal landscape surrounding a claim for protection against climate change. This exploration involves a short breakdown of the legal situation, identifying potential responding states and shedding light on obstacles to such a claim. Finally, I offer a brief reflection on the personal journey of delving into the complex world of climate change.

Laying the foundation for my framework

Fueled by the desire to empower children, I embarked on my search to build this framework which would ideally allow children to claim protection against climate change. Quite soon, I encountered the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), a landmark human rights treaty that stands as the most widely ratified in history. In it enshrined are rights specifically tailored to address the unique needs and vulnerabilities of children.

The Convention is accompanied by three Optional Protocols, each addressing various aspects of children’s rights. Among these protocols, the Optional Protocol on a Communications Procedure (OPIC) stood out as particularly intriguing. This protocol introduces a way for individuals to complain if a state violates their rights under the Convention. By using this process, children can directly inform the Committee on the Rights of the Child that a specific state has not followed the rules. So, the UNCRC, along with the OPIC, gives children a way to speak up and claim protection against climate change

Climate justice beyond borders

In considering the OPIC as a tool for lodging complaints, I read about another compelling development. Historically, responsibility for the majority of greenhouse gas emissions in the earth’s atmosphere can be attributed to industrialised countries (Global North). This contribution is also reflected in the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities. Essentially, this principle recognizes that all countries share an equal responsibility for protecting our environment. However, it also acknowledges that the Global North, has a bigger obligation due to their historical contributions to climate change and their relatively greater resources compared to the Global South.

In this context, it seems logical to consider filing a claim against a country from the Global North, given their large share of responsibility for climate change. Yet, complications may arise when the child bringing the claim (claimant) lives outside the territory of the defending state. This situation can create challenges to the admissibility of a claim. Fortunately, the Committee on the Rights of the Child has recently opened its doors for extraterritorial jurisdiction. This means that a claimant need not necessarily reside within the borders of the defending state to bring a claim. However, it is essential to note that the Committee has established certain requirements and conditions for such extraterritorial cases, which l will explore further in my thesis. Consequently, using the OPIC as a framework allows claimants to bring claims against a state without geographical boundaries.

Obstacles and the age-old question of enforcement

Using the OPIC to file a claim comes with some limitations that are important to understand. Firstly, for an individual to file a claim against a particular state, that state must be a party to the OPIC. If a claim is lodged against a state that is not a signatory, it will be immediately dismissed. Secondly, before filing a claim under the OPIC, the person making the claim must have exhausted domestic remedies. This means that the claimant must first use the judicial complaint procedure available under national law before bringing a complaint to the international level. A claimant is excepted from exhausting national remedies if they can substantiate that national remedies are either unreasonably prolonging the application or are unlikely to bring effective relief. Lastly, it is crucial to know that the Committee on the Rights of the Child cannot force a state to cease certain behaviors with its decision. While it can make recommendations, it does not possess the power to compel a state to take or cease a specific action. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that the weight of a decision from such an international body should not be underestimated, and it can have significant political influence.

A short reflection

Throughout the journey of researching and writing my bachelor thesis on climate change and children’s rights, I found myself confronted with the harsh reality of the current state of our planet. Reading paper after paper, I encountered heart-breaking statistics and narratives documenting the mortality and suffering of children around the world due to of climate change. It was sobering to realise that this is unfolding right under the watchful eyes of the 196 states who pledged to safeguard children.

Yet, there is hope. Domestic and international cases are building up, demonstrating growing awareness and willingness to address the issue. The paths to claim protection are there; they exist within the frameworks and international agreements that bind nations. While the road ahead may be challenging, it is a path we must continue along, knowing that change is possible, and our collective efforts can make a difference.

Read more

In my thesis, I explore the critical intersection between children rights and the threat of climate change. In doing so, my thesis seeks to answer the following research question: 'How can children claim protection against climate change under the Third Optional Protocol to the UNCRC?’.

If you would like to read more, you can download the full thesis here.

22 March 2023 - By Tahreem Masood Rehman

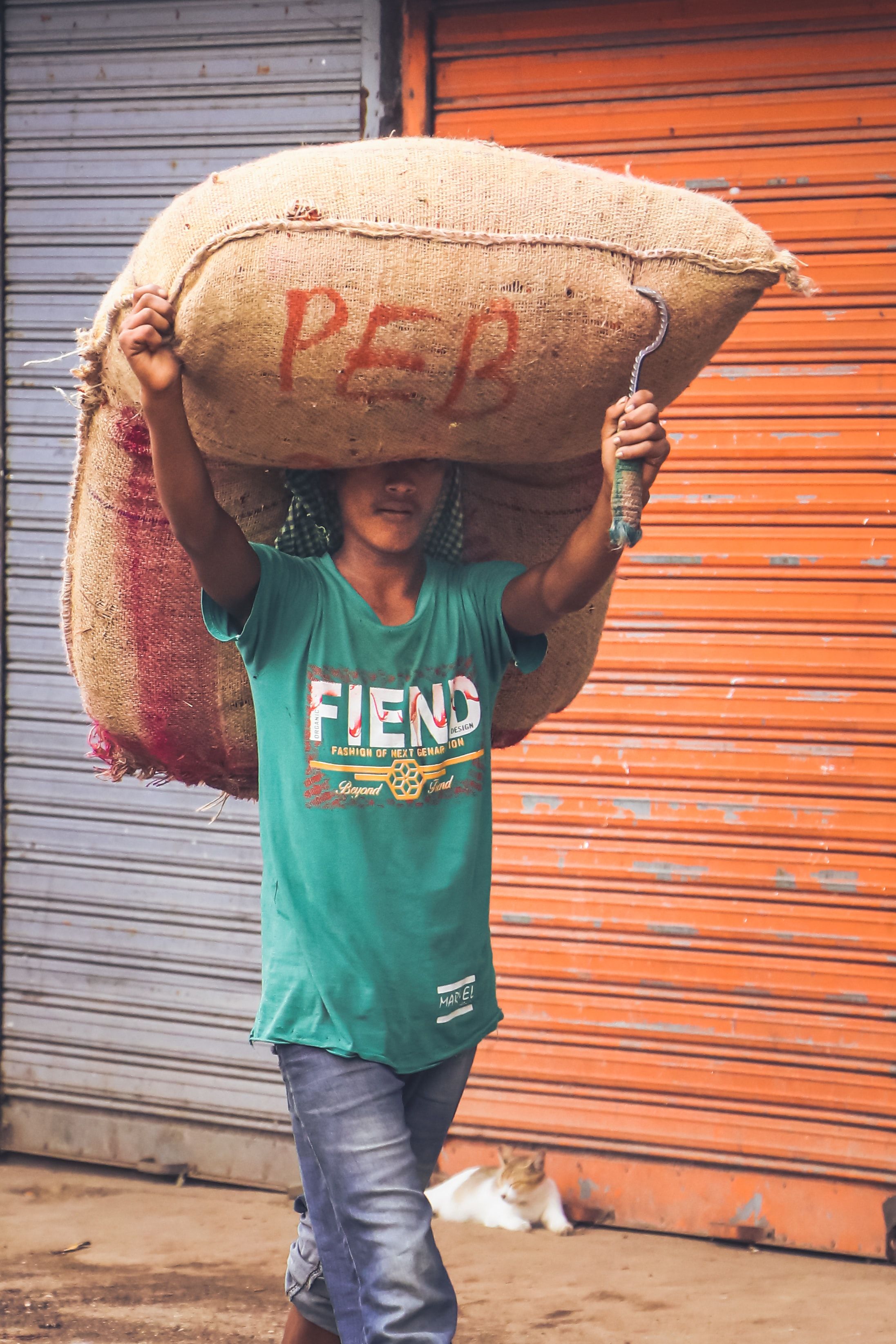

In 2016, Tayyaba, a 10-year-old maid, was rescued from the home of her abusive employer in Islamabad, Pakistan’s capital. Photos of her bruised and bloodied face went viral on social media and sparked public outrage in Pakistan. However, Tayyaba’s case is not an isolated incident. In Pakistan, there are estimated to be as many as 14 million child labourers aged under 15.

This blog first outlines Pakistan’s obligations under international law and its domestic legal framework in relation to child labour. It then discusses Tayyaba’s case and uses it to illustrate the challenges Pakistan faces in meeting its obligations concerning child labour under international law.

Pakistan’s obligations concerning child labour under international law

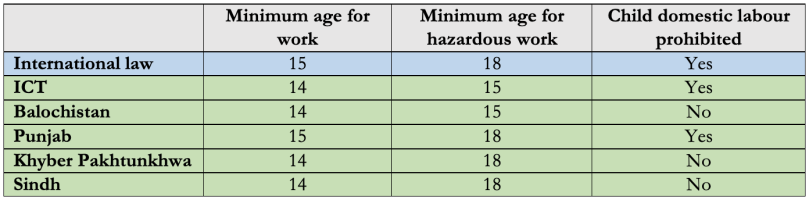

Pakistan is a state party to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) which it ratified in 1990. Among the obligations, UNCRC creates for Pakistan is the requirement to ensure that children are protected from all forms of economic exploitation and hazardous or harmful work (see Article 32). Additionally, Pakistan has ratified the International Labour Organisation (ILO) Minimum Age Convention and Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention.

The Minimum Age Convention sets 15 as the general minimum age for employment (13 for light work) and 18 for hazardous work. However, it also permits countries to set a temporary minimum age of 14 for employment (and 12 for light work) if its educational infrastructure and economy are insufficiently developed. Similarly, the minimum age for hazardous work can be reduced to 16. The Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention prohibits all forms of slavery (including debt bondage) and “work which could harm children’s health and/or expose them to danger.”

Pakistan is a state party to the UNCRC, which it ratified in 1990.

Pakistan’s domestic legal framework for child labour law

The 18th Amendment to Pakistan’s Constitution, passed in 2010, devolved all child welfare and labour issues to the provincial level. However, until a province repeals or adopts a replacement law, pre-existing federal laws on children’s rights remain in effect. Consequently, laws on child labour vary according to where the child is in Pakistan (there are four provinces in Pakistan plus the Islamabad Capital Territory (ICT), which is a federal territory).

One example of this is that under federal law the minimum age for employment is 14. This is also the case in the provinces of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Sindh, however, in Punjab, it is 15. Another example is that the federal-level 1991 Employment of Children Act (ECA) sets the minimum age for hazardous work as 15 (which is not compliant with international law). However, at the provincial level in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Sindh, and Punjab the minimum age for hazardous work is 18 (which is compliant with international law).

A final example relates to child domestic labour. On 4 August 2020, Pakistan’s Cabinet amended the ECA to add domestic labour to the list of occupations that it is prohibited for children to work in. Due to the 18th Amendment this currently only applies to ICT. It could be adopted by other provinces by way of an assembly resolution, but none have yet done so. However, the Punjab Domestic Workers Act 2019 prohibits the employment of children (under the age of 15) in households in any capacity.

Table: Minimum age for child work and hazardous work by province in Pakistan

The reality of child labour in Pakistan

The exact number of child labourers in Pakistan is not known. This is, in part, because only 34 percent of children are registered at birth. As a result, it is hard to establish both how many children there are in Pakistan and the age of those working. Pakistan’s only completed National Child Labour Survey, conducted in 1996, recorded 3.3 million child labourers (a second survey begun in 2019 but is not yet completed). However, unofficial estimates by non-government organisations place the number of child labourers to be significantly higher at around 10 to 14 million.

Unofficial estimates suggest there are up to 14 million children engaged in child labour in Pakistan.

According to the ILO domestic labour is when underage children carry out hazardous household tasks (e.g., using dangerous objects like knives or hot pans) and/or work in slavery-like conditions. Child domestic labour is particularly hard to obtain accurate information about because it happens in private spaces. Additionally, a substantial proportion of Pakistani society does not see household work as constituting ‘labour’ for a child. Notably, as discussed above, domestic labour was only recently added to the list of occupations prohibited for children under the ECA. Children engaged in domestic labour in Pakistan are disproportionately girls from rural areas. Familial poverty is the main ‘push’ factor for children to work as domestic labourers (including to pay off family debts, finance a sibling’s education, and fund doweries). In 2004 the ILO estimated there were 264,000 child domestic labourers in Pakistan.

Child domestic labourers are also at high-risk for other harm. Many relocate from rural to urban settings (where most domestic labour takes place) and live in their employers’ homes far away from their families. Domestic labour happens behind closed doors and children are often dependent on employers for basic needs such as food, and accommodation. This makes child domestic labourers particularly vulnerable to abuse (psychological, sexual, and physical), debt bondage (i.e., working to pay for the cost of their food, accommodation, etc.), and deprivation of other rights (e.g., the rights to play, education and healthcare).

Violence against child labourers in Pakistan typically only comes to light in cases involving extreme brutality. Between January 2019 and 2020, around 300 child labourers were rescued by the Child Welfare and Protection Bureau in Punjab alone. However, in this period only 51 cases of violence against child labourers were reported by Pakistani media.

The Tayyaba case

Among the cases that did garner media attention was the case of Tayyaba. The 10-year-old was employed as a maid for a judge, Raja Khurram Ali Khan, and his wife, Maheen Zafar. Tayyaba worked for the couple for two years before neighbours alerted police to her abuse in December 2016. Photographs of Tayyaba shared online show her bruised and bloodied face and sparked public outrage. According to the Pakistan Institute of Medical Science, other injuries included burns on her hands and feet.

Tayyaba’s background was typical of a child domestic worker in Pakistan. Her family was struggling to make ends meet. Her father lost a finger in an accident and was unable to work. Her mother needed surgery. Tayyaba was sent to work in Islamabad, a four-hour drive from where her family lived in a village near Faisalabad in Punjab province.

Khan and his wife were both charged with “cruelty to a child” under Section 328-A of the Pakistan Penal Code (they were not charged with employing a minor because, at the time, domestic labour was not a prohibited profession under the ECA). However, in 2017, Tayyaba’s father attempted to have the charges against Khan and Zafar dropped by offering his formal ‘forgiveness’. In Pakistan, criminal cases are filed by victims or their families, not the state. Plaintiffs can choose to drop cases (even for serious charges) by pardoning the accused “in the name of God.” Critics of this right to ‘forgive’ say that such pardons are often the result of a financial payment to victims (or their families) and enable the wealthy to avoid punishment.

In Tayyaba’s case, the court rejected her father’s pardon and took suo moto notice of the case (i.e., when a court acts on its own accord without request from involved parties) warning that: “no agreements can be reached in matters concerning fundamental human rights.” In April 2018, Islamabad High Court found both the accused guilty and sentenced them to one-year in prison and a 50,000 rupee fine (approximately $750). In June 2018, that sentence was increased to three years by the same court. In January 2020, it was again reduced to one-year by Pakistan’s Supreme Court.

Although Tayabba’s father initially told officials that the judge and his wife had not hurt his daughter and that she had fallen down the stairs, he later admitted to the BBC that he had lied and that Khan had paid for his lawyer and promised to get him a house and a car as a “token of sympathy”.

Child domestic labour happens behind closed doors making children particularly vulnerable to abuse, debt bondage, and deprivation of other rights.

Issues highlighted by the Tayyaba case

Pakistan faces serious challenges in tackling the problem of child domestic labour. This section highlights three key issues using the Tayyaba case to illustrate them.

Firstly, the high-profile case of Tayyaba and, later, Zohra Shah (an eight-year-old maid who was beaten to death in 2020 after accidentally releasing her employers’ parrots) led to domestic labour being added the list of prohibited occupations for children under Part 1 of the ECA. The move was welcomed by children’s rights activists in Pakistan. However, as already discussed, because of the 18th Amendment this addition to the ECA currently only automatically applies to the ICT. Therefore, child domestic labour is not prohibited in other provinces of Pakistan (except for in Punjab due to the 2019 Punjab Domestic Workers Act). Beyond the legality of child domestic labour, this points to a broader problem in Pakistan. Because child labour laws vary between provinces this creates uncertainty in the law (particularly when children are sent to other provinces to work) and contributes to a lack of enforcement.

Secondly, Tayyaba’s case shows how economic inequalities drive child labour in Pakistan. Like most child labourers, her family was poor. According to the World Bank in 2018, 21.9 million people in Pakistan lived below the poverty line. The Covid-19 pandemic, devastating floods in the monsoon season of 2022, and poor economic management have exacerbated the gap between the rich and poor. Between January 2022 and 2023, the price of basic goods rose 41 percent. According to UNICEF 22.8 million children (equivalent to 44 percent of children aged 5-16) do not attend school in Pakistan. When families depend on child labour for their survival, legislation alone is unlikely to end the practice.

Thirdly, Tayyaba’s case illustrates how the right to ‘forgive’ the accused can be utilised by the wealthy to try and avoid punishment for their crimes. This is particularly relevant to child labour because the families of underage workers are disproportionately likely to be poor compared to their employers. Therefore, even if laws are passed to restrict child labour, they are unlikely to be enforced if ‘forgiveness’ can be bought by those that breach them.

For a more in-depth analysis of the legal system for child protection in Pakistan, you can download my thesis here.

By Florentina Pircher - 19 May 2021

Every child has certain universal human rights that should always be protected, right? But who is supposed to grant them these rights and afterwards protect them? Normally, states are responsible for protecting the rights of children living in their territory (whether they are citizens or not). But what if a state delegates this responsibility to somebody else, or if a state is not recognised by the international community? An example of such a situation can be found in the Tindouf refugee camps in Algeria. The camps are governed by the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), but not every state accepts that this Republic is a proper country. This also means that it cannot become a member to international conventions, such as the ‘Convention on the Rights of the Child’. That is why when writing my bachelor thesis, I decided to look at this situation a bit more closely and explored the research question ‘Who is responsible for the international human rights of Sahrawi people living in the Tindouf refugee camps?’. In this post I will focus specifically on children’s rights.

Context – The Tindouf Refugee Camps

Of course there is a lot to I could say about the history of the Tindouf camps, but essentially what is relevant for this blog post is this: The people living in the Tindouf refugee camps are members of the ‘Sahrawi people’, a nomadic people from Western Sahara. When the territorial conflict about Western Sahara erupted into violence in 1976, they fled just across the border to the Tindouf area in Algeria. The United Nations refugee agency UNHCR has recognised that the Sahrawi people living in the Tindouf camps have the legal status of being refugees. The camps are controlled by Polisario, the liberation movement of the Sahrawi people, which is fighting for the Sahrawi’s claim to the territory of Western Sahara. In 1976, the Polisario proclaimed the SADR as an independent state, which is considered an unrecognised state. Although quite a few countries, as well as the African Union, recognize the SADR, not all countries do and therefore it is unable to sign most international treaties. Therefore, the camps are inhabited by a population of refugees that lives under what most of them consider their own government, but others consider to be an unrecognised entity, not bound to respect children’s rights.

The Issue – Non-State Actors and Why They Matter

Usually, when considering who is responsible for someone’s children’s rights, we turn to the state that is in control of the territory or the children in question. In the case of refugees, the international legal system sets out that the state which they are in must guarantee the refugees the same rights as its nationals.

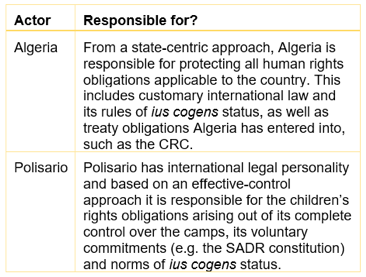

This means that according to the existing framework Algeria, as the camps’ host state, is considered the primary actor in this scenario. It also has ratified various conventions, including the ‘Convention on the Rights of the Child’ (CRC) and the ‘1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees’. This means that Algeria has responsibilities such as treating nationals and refugees alike when it comes to access to elementary education and other public services. At first sight, the situation is therefore quite clear, Algeria is responsible for the international children’s rights of the Sahrawi children living on its territory, right? Yes, but…

From early onwards, Algeria has delegated all responsibility over the camps to Polisario. They recognize the SADR as an independent state, and the Polisario as its government. This means that Algerian authorities are not present in the camps and do not, for example, provide education in the camps. It happens surprisingly often that people find themselves in a situation in which not a state, but another type of actor is making the calls when it comes to their children’s rights protection. This is also the case with the Sahrawi refugees in the Tindouf camps which is why considering Algeria alone as responsible is not very useful from the perspective of a child living in the camps. However, since not all countries recognise the SADR as a country, internationally it is usually seen as a ‘non-state actor’. This term is usually used for bodies that are not states but still relevant in the international legal community, such as international organisations like the United Nations, corporations or armed opposition groups. They cannot become a signatory to conventions like the CRC. Nevertheless, it is increasingly accepted that non-state actors should also be responsible for the rights of the people they are in control of. Legally speaking, the International Court of Justice has accepted this possibility, as long as the actor in question has ‘international legal personality’. Whether a non-state actor will fulfil this qualification, and which obligations it has if it does, depends on the actor’s purpose and function. This still sounds quite vague so to put it more concretely, here are some of the obligations that non-state actors could (or should) be bound by:

- Obligations arising out of exercising effective control over people or territories: An actor exercising government-like functions should be bound by children’s rights norms when what they do can affect the rights of the children under their control. For example, when a governing body is in control over water supply, they have to make sure that access to this water is equally accessible to all children.

- Self-imposed obligations: Many non-state actors actually voluntarily declare that they will adopt certain human and children’s rights standards. Arguably this can give rise to the actor being internationally obliged to respect these standards.

- Ius cogens norms: These are rules of international law that must be complied with at all times and cannot be derogated from, no matter by whom. The argument is that non-state actors with international legal personality should also have to follow the generally accepted rules within which they operate. Some of these rules are human rights norms, for example the prohibition of torture.

Human Rights Obligations for Polisario?

These obligations should also apply to Polisario (the Sahrawi governing body). Firstly, it has international legal personality based on its role of representing the Sahrawi people, as accepted by the UN, and secondly, it exercises actual control over the Tindouf camps and its inhabitants. This control is in many ways similar to the control a regular government usually has over a country (deciding who gets to enter, applying its own criminal and juvenile law, etc). Therefore, this almost complete control over the camps could be a reason to hold Polisario responsible for certain children’s rights obligations. This is supported by the fact that Polisario, or rather the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, the state that Polisario proclaimed, has ratified the ‘African Charter on Human and People’s Rights’, although not the ‘African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child’. It also has its own human rights catalogue included in its constitution, which contains the right to free education and the obligation to ensure protection for children. These ‘national’ or regional commitments to human rights can arguably also give rise to international obligations in the field of children’s rights.

As you can see summarised in this chart, there is a lot of room for seeing Polisario responsible for certain rights of Sahrawi children, in addition to the obligations of Algeria.

Still, whether non-state actors can have children’s rights obligations remains disputed by some. Looking at the goals that international children’s rights law is supposed to achieve however, it seems like denying that Polisario can hold certain children’s rights obligations bypasses the reality of a child living in the camps and experiencing almost exclusively the governance of Polisario. Children’s rights are supposed (a) protect children and (b) apply to every child equally, independent of nationality. Consequently, if children’s rights are supposed to protect every child equally, they should also be granted to those living under the control of a non-state actor.

If you want to know more about the situation in the Tindouf camps, then follow our upcoming posts and vlogs from our field research trip!

You can read my complete thesis on this subject here.

A map of the territory of Western Sahara and the Tindouf camps.

SOURCE: Omar-Toons. (2011, 15 March). Western sahara map showing morocco and polisaro [Illustration]. Wikipedia.

Who is responsible for providing education in the Tindouf camps?

SOURCE: Ammi, L. (2018). Sahrawi refugees in Algeria [Photograph]. European Union.

Water tanks in the Tindouf camps.

In my original bachelor thesis, I also analysed the role of other actors present in the Tindouf camps. Anyone interested in reading the full version can find the complete paper here.