Sahrawi controlled areas: freedom from violence

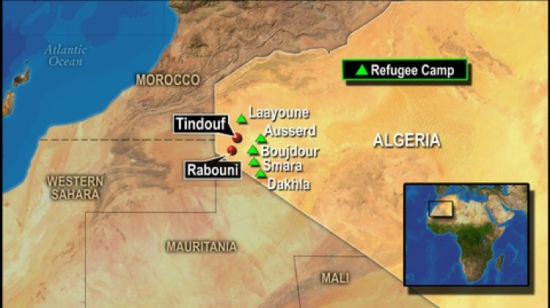

In 1976, a large part of the indigenous Sahrawi nomadic population fled the Western Sahara because of ongoing violent conflict over the territory. They settled in refugee camps just over the border near Tindouf, Algeria. To this day, Sahrawi families are living as refugees in these camps. As part of our study on the development rights of children living in unrecognized states, we visited the camps and studied the rights of children living here. Based on what children indicated we should focus our study on, this case study focuses on the child’s right to freedom from violence. In particular, we focus on violence between children and corporal punishment in the family and at school. Below you find all the blogs and vlogs related to this case study.

19 May 2023 - Tajra Smajic

As a parent, should I stop my children from fighting? As a teacher, should I beat children when they continue to disrupt the class, or when they refuse to pray? When confronted with such ethical questions, people’s choices are generally influenced by the normative rules that they know. For example, they are influenced by what their religion tells them to do, how the state and society tells them to act, or what their family thinks. We also have our own personal norms. Sometimes, these norms may contradict each other. Maybe you personally feel that you shouldn’t beat your children, while your family expects you to lightly beat your children when they misbehave. In such situations, what do you do?

Our recently published paper Navigating conflicting normative orders: when violence isn’t violence unpicks this dilemma as experienced by parents, educators, and children themselves living in the Sahrawi refugee camps near Tindouf, Algeria. We found that the Sahrawi participants in the study (both adults and children) used multiple normative orders to frame their understanding(s) of violence against children. Namely: the international legal order, the religious (Islamic) legal order, the national legal order, the traditional normative order (Urf), the community, the family and the school – (you can read more about these normative orders here and here).

One of our key findings was that these different normative orders led to different conclusions about when violence against children is and isn’t permitted. Moreover, in contrast to most scholars of norm pluralism, the findings of our case study led us to theorise that rather than choosing between these contradictory norms, participants attempted to reconcile them. To explain this, we used the Sartrean concept of mauvaise foi to propose a new model for understanding how people deal with contradictory norms. Namely, we suggest that by redefining core concepts of norms, such as ‘children’ and/or ‘violence’, interviewees tried to resolve the apparent tensions between norms of different normative orders.

In this blogpost, I briefly introduce some of our key research findings in relation to contradictory norms that influenced research participants’ understanding(s) of violence against children in the Sahrawi refugee camps and illustrate how paradoxical reasoning was used to resolve the conflict between them.

In 1976, a large part of the indigenous Sahrawi population fled Western Sahara because of fighting between the Moroccan army, the Mauritanian army and the Polisario (Sahrawi liberation movement) over the territory. The refugees crossed the border into Algeria where the Algerian government allowed them to set up refugee camps – supported by the UN Refugee Agency – which are run by the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) government-in-exile. To this day, the conflict remains unresolved. Consequently, multiple generations of Sahrawi children have grown up in the refugee camps. Currently, the UN Human Rights Council estimates there are approximately 65,000 children living in SADR-run camps.

To our knowledge, very little academic research has been conducted into the situation of children living in SADR refugee camps. This knowledge gap was the starting point of our inquiry into the development rights of Sahrawi children and different norms related to the protection/violation of these rights. Through exploratory interviews with Sahrawi children, we identified violence against children as a key issue. In particular, the children interviewed stated that they regularly experienced two forms of violence: 1) fighting between children and 2) beating by adult family members and teachers. As such, we decided to focus our case study on the right of children to be free from all forms of violence as provided for in Article 19 of the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child (UNCRC).

Our research was conducted by way of qualitative interviews. Two members of our research team travelled to the five Sahrawi refugee camps located in Algeria. Additionally, one research trip was made to a part of Western Sahara under SADR control. Together with four trained local researchers, our team interviewed 93 participants during the trips (36 children and 57 adults). We asked them questions on different social and individual norms as well as what they thought about children’s rights protection and violation, particularly in the context of violence against children.Research findings: Conflicting norms

We started all our qualitative interviews by asking research participants about the child’s right to live free from all forms of violence. Almost all adults that we spoke to indicated that Sahrawi children in the camps have and/or should have this right. Most also argued that children in the camps do not experience any violence. However, despite this, several interviewees also went on to discuss circumstances in which they believed that violence against children could be acceptable and indeed does occur.

Broadly speaking, we were able to divide such apparently contradictory responses from interviewees into two categories. Namely, 1) responses that redefined ‘childhood’ and 2) responses that redefined ‘violence’. We purposely use the word redefined rather than defined because all participants were either already aware of, or were made aware of, and mostly expressed agreement with the (international legal) norm that childhood ends at the age of 18 and that violence is any act imposing serious psychological or physical hurt.

Responses that redefined childhood centred on reducing the age at which childhood ends. For example, one male teacher we interviewed reasoned:

These children who live in other countries they stay children until the legal age. But here, because of the extreme conditions, we say that the children become adults before the legal age. The Sahrawi children face so many problems in here and because of the hard living I think the child becomes [an adult] at 12 or 13 years old […].

In another interview a mother stated:

As the law for all the world say, it is from birth until 18, but I think that it is from birth to 16 years old.

Responses that redefined violence typically either minimised fighting between children as not constituting violence or distinguished a ‘light’ beating from a ‘serious’ beating, with only the latter constituting violence. For example, one interviewee who was a political actor and father stated:

[Children] might hit each other. But I don’t think that this is part of the right to be free from violence. So this is violence between children, they talk badly about each other, and they hit each other. But this is a thing of children.

Similarly, another father stated:

There are two types of beating, hard beating and simple one. In fact, beating is not correct but the family or the parents sometimes, when the children do something wrong, they get angry and they beat the children, but only simple beating to guide them to the right way.

Celebration of Independence Day in the SADR camps / photo by researcher

Navigating conflicting norms

Most research on norm pluralism suggests that when people are confronted with contradictory norms, they will make a cost-benefit calculation and choose between them. However, in our paper we show that there is another way in which people navigate conflicting norms. Namely, instead of abandoning one norm in favour of another, they seek to align conflicting norms by redefining core concepts.

For example, by redefining the age limit of what constitutes a ‘child’, respondents appeared to be reconciling (Islamic) religious norms that it is acceptable to lightly beat a child aged over 10 (in some circumstances) with the international legal norms that all children have the right to live free from violence. Similarly, by excluding violence between children from the definition of violence and distinguishing ‘educational’ and/or ‘light’ beating from ‘heavy’ beating, Sahrawi interviewees were able to align their family, community, and school norms (which see educational and/or light beating as permissible) with the position that children living in the camps were not subject to violence (in accordance with international legal norms).

This paradoxical reasoning, we argue, is an example of the Sartrean concept of mauvaise foi (bad faith). This is not a deliberate act, since deliberately lying to oneself is not possible. As Sartre writes: ‘Nobody will dispute indeed that, if I deliberately and cynically attempt to lie to myself, I must completely fail in this undertaking.’ Rather, it is a consciousness that is hiding something from itself. This becomes evident in the ambivalence that interviewees often exhibited when they were questioned further about their views on violence against children. For example, one father stated:

In my own understanding, it is wrong to hurt the children physically […] So, when someone hurts a child physically, it affects their brain, their emotions negatively and their relationship with the society. […] whatever the parents say or do, like light blow, and as we experience it, being a child in this society, [a light blow] does not affect the children, except doing hard punishment or repeating a physical punishment, that could affect the children. But anything else, it does not affect them.

According to this interviewee, it is wrong to hurt children physically because it affects them. However, if you lightly beat children it does not affect them and therefore it is not normatively wrong. From a viewpoint of logical consistency this is problematic, since beating normally causes physical hurt. If it wouldn’t hurt at all, it probably would not be considered beating but rather be described as touching, and it would not be considered a punishment or correction.

This blogpost has briefly introduced our research on the way in which the Sahrawi’s navigate different normative orders when it comes to understanding(s) of violence against children. It shows us that there is another way of dealing with a situation in which one is facing different conflicting norms: instead of choosing between them, it is possible to redefine core concepts of these norms so that they can be aligned by way of the Sartrean concept of mauvaise foi. However, we also established that such an exercise does not sit comfortably with the person doing so, because in denying the conflict between norms, one has to lie to oneself.

If you find this interesting and want to read more, you can find our full-length paper here.

By Marieke Hopman - 28 February 2023

Dear all,

As most of you know, in 2019 we started a study on the rights of children who are living in the Sahrawi refugee camps near Tindouf, Algeria. Based on our first interviews with children in the camps, and per their advice, we chose to focus this case study on the child’s right to be protected against violence. In particular, we focused on fighting between children, and ‘educational’ beating by parents and teachers as these are forms of violence against children that occur regularly in the camps.

Based on the research results and the theory of change we developed, we decided that the most effective way to share the research results would be to organise workshops for children and adults. After some delay due to Covid-19, I was finally able to travel back to the camps this January. Below, I explain about the different parts of the workshops and how they were received. Please note that all the workshop materials are made available at the bottom of this blog and can be used free of charge.

Workshop part 1: How does it make you feel?

After a brief introduction, we started the workshop by inviting participants to reflect on how certain situations make them feel. One by one, we presented three different situations:

Situation 1: children are fighting

Situation 2: a teacher beats a child with a stick

Situation 3: a parent beats a child

We also presented four feelings: angry, sad, scared and happy. We asked participants to think about how a situation, for example when children are fighting, makes them feel. Without discussing, they would pick a sticker that represented their feeling, and put this sticker on the white paper underneath the poster with that situation.

Second, participants were invited to share which emotion they chose and why. We started by asking children and then invited adults to react.

Generally, participants agreed that fighting between children was not a good thing but at the same time not everyone thought that it was really a problem – especially the adults. Regarding beating of children by teachers or adults, opinions were different and often lively discussions followed. Some children argued that beating is good or necessary. Others argued that children should not be beaten. Some views that were shared by Sahrawi children:

Using stickers, participants indicate how a situation makes them feel

A child puts a sticker on the white sheet, to indicate how she feels about children fighting each other

- “I can’t accept it when a teacher beats a child, because it will only make it worse, and it doesn’t solve anything.”

- “I like it when they beat children, because it is the only way in which they can make children understand.”

- “Beating is the only way how children can respect their parents. They need to beat them.”

- “My parents never beat me. When I see other parents beat their children, I feel scared”

Adults’ perspectives on beating children also varied. They largely seemed to agree that while beating is not desirable or preferred, it is sometimes necessary. However, some argued that it is never necessary, or even when it is “necessary” in the sense that one cannot move a child to behave better, beating is not effective and therefore still not helpful.

Workshop part 2: Reactions to child behaviour

In the second part of the workshop, we invited participants to reflect on what, they thought, was the best reaction to two situations. The first situation was about a child misbehaving in class. The second was about a child behaving well by helping another child.

Participants were invited to choose between five different reactions and vote (using a sticker) for the reaction (pictured) they liked best:

Child misbehaves in class

Child helps another child

Reaction 1: adult and child talk about it

Reaction 2: adult gives child a compliment

Reaction 3: child asks adult for help

Reaction 4: adult gets angry at child

Reaction 5: adult beats child

The exercise was a good conversation starter. It gave the incentive and space to the participants to start talking about in what situations it would be good for adults and children to talk, when it would be good for the adult to get angry at the child, when it would be good to give a compliment etc.

Workshop part 3: children’s rights and the power of compliments

Initially, our plan was to mostly invite participants to talk. To have a conversation was to be the main goal of the workshops. However, after a first trial workshop, the Sahrawi teachers indicated that it was necessary to add more content from my side. They suggested that I would give a short lecture where I would share information from a children’s rights perspective including alternative ways of changing children’s behaviour, so that participants could go home having learned something new. I personally struggled with this assignment as I feel very conscious about being a white, Western person who comes to a different society and tries to change some of their tradition/culture (both fighting between children and (lightly) beating children do currently seem part of the Sahrawi culture, although it also seems that beating children is already changing to be less accepted). However, since this was the explicit wish of all Sahrawi involved, I added a part where I spoke for about twenty minutes about the content of the child’s right to protection from violence, the findings of the study, and what we know from research about changing child behaviour.

You can find the whole draft text of this short lecture here, but in short, I made three main points:

- Any physical act that is intended to hurt a child, including light beating for educational reasons, and including fighting between children, is illegal according to international law. It violates the child’s right to protection from violence.

- Fighting between children in the camps is a problem. We know this from what children told us in our study. It should be taken seriously, and three things can be done to prevent this occurring more: 1) taking the problem seriously; 2) combatting boredom by creating child-friendly places and distributing materials; 3) creating rules and subsequent protection mechanisms, together with children and adults.

- If one wants to change children’s behaviour, we know from research that it is much more effective to reward good behaviour, for example by complimenting children, than to punish bad behaviour.

After my talk, three Sahrawi teachers also shared their experiences of using alternative approaches to physical punishment to change their students’ behaviour. This was very powerful, because instead of presenting general theory, they could share what actually worked in their experience with Sahrawi children.

After these presentations, some more discussion would follow. In the end, we invited children to come to the front, when we gave each child a set of memory cards with the images used in the workshop. We ended the workshops by playing memory with the children – which they seemed to really love!

Presenting the findings of the study

Teachers share their experiences

Children playing memory

Reflection

Generally, I was quite happy with the workshops. One thing that I though was really powerful, was how Sahrawi teachers stepped up and were very quickly teaching the whole workshop in Hassaniye (the Sahrawi language), while I only added the short presentation on the research results. Another thing that I very much liked were the materials. All images were created by illustrator Iris van de Winkel, and the choice of material and printing process was the work of Rik Hurks / Mannen van 80. Fun fact: Iris got involved in the project after I saw some of her work behind the window in the street where my children go to daycare and I contacted her to ask if she’d be interested to create some illustrations for us.

The workshops in my view had several direct and indirect positive learning points:

- There are some forms of violence against children occurring often in the Sahrawi camps. It is, perhaps, possible to change this

- We practiced talking about feelings (with the help of posters and stickers)

- It is good to listen to children’s views and ideas

However, what I am not sure about, is whether these workshops will have much effect. It seems quite limited to do only seven workshops: five in Smara and two in Dakhla. This means that we reached only a very limited amount of people and only in two out of the five camps. Seven workshops are only a small drop in the ocean. That said, we did distribute the memory games, and these are made from PVC material so that they should last a long time, even in the difficult climate in the camps. So, I am hopeful that children will keep playing this game, and that this will keep the conversation going. As one of the teachers said: “The workshops have planted a seed. Now, let’s hope that it will grow.”

Materials

Please find below all materials used in the workshop, available for download and free for use. If you do use the materials, we would appreciate if you mentioned the Children’s Rights Research project and our website (www.childrensrightsresearch.com) as your source. We would also be grateful if you would let us know how you’re using the material by contacting us at

To download the materials, use the buttons below:

22 February 2022 - Florentina Pircher

One of the case studies in the research project on children’s rights in unrecognised States is the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), a State claiming the territory of Western Sahara, large parts of which are currently under control of Morocco. While the SADR government is mostly based in Algerian refugee camps, it also controls a strip of land of the Western Sahara territory. The SADR refers to this territory as ‘liberated territories’, which are separated from the Moroccan side of the Western Sahara by a huge sand wall and some remaining landmines, meaning that the only way to travel there is from the Algerian side. There is very little information about the children living there, so we decided that it was important for me to visit the area and try to get at least an impression of what life is like for children living in this remote area. However, doing research in such an area far into the desert involves many unforeseen challenges and turned into quite an adventure.

For starters, as a foreigner, you are not allowed by the SADR government to go on this trip unaccompanied. There are various security measures that you have to stick to, including being accompanied by military personnel at all times of the trip. This means that you have to (1) coordinate with the SADR authorities for which days they can arrange trips for foreigners to the ‘liberated territories’, (2) do the trip together with other foreigners wanting to visit the area, as there are limited security cars and staff members available, (3) have the driver and car that will be driving you authorized by the government. Just to get that done I had to go to the administrative centre of the camps three times, again requiring a driver and having him authorized to drive me.

Additionally, there was the cultural aspect of wanting to travel with our female translator so she could help with interpreting interviews with girls. I learned that in many Sahrawi families unmarried women cannot travel without a (male) family member for protection, especially for such a long trip. There was a lot of back and forth before we found someone who would agree to accompany her.

(2) With limited equipment and tools available in the desert, there was no way to get our car back to speed for driving us back.

Of course, there were many other things that made the trip difficult or uncomfortable, such as there not being any internet and phone reception for me to contact Marieke and ask for advice, or simply the lack of sanitary facilities. The most challenging factor by far were the unreliable cars. Driving on such rough, largely uninhabited terrain makes you completely dependent on the car you are travelling with. Unfortunately, we did not only go through quite a collection of flat tires (perhaps unsurprisingly, seeing as there was no road), but after a 15-hour drive into the desert, the car in which our translators and I were travelling completely broke down. At least there was still space in the car of another organisation that was with us on the trip. At that point we only had one security car accompanying us left (the other one having broken down too), so the whole group had to move around together at all times, leaving me with little control over where we would go.

This is definitely not ideal if you are trying to find children that you can interview anonymously in an extremely sparsely populated area. Everyone in the group of foreigners that we were with was from different organisations and had different locations that they wanted to head to. I had the strong feeling that my agenda was not being taken into account by the security staff planning our itinerary. There were times where I did not know whether we would be able to do any interviews at all, which I found quite stressful because I did not want to see all the money and time spent on this trip wasted. At this point, I decided to explain again very clearly what we were here to do and, in the end, two primary school visits were arranged, and we got to do several interviews with children there. I was very relieved, and very exhausted.

While all this was quite an adventure, I think it was important to get some insight into what the area looks like and what children living in the ‘liberated territories’ experience, although I wish that we could have done more. Still, I think that the fact that it was so difficult to get there and get interviews done just makes it even more important that we tried.

8 February 2022 - Florentina Pircher & Marieke Hopman, Wesside Stories

In our next vlog we will share footage of us sharing our research results in the Sharawi refugee camps, after we travel back in March 2022. For now, we share this bonus video: the animals of the Sahrawi people!

1 February 2022 - Florentina Pircher & Marieke Hopman, Wesside Stories

After returning from our research trips, we had to decide how to continue from here. What would be the best way to publish our research? How could we make sure that what we do with our research results, will also benefit both the children in the Sahrawi refugee camps, and the children living in the Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara? And how do we navigate the situation created by the Covid-19 pandemic?

24 January 2022 - Florentina Pircher & Marieke Hopman, Wesside Stories

In this video, Florentina embarks on a mission to visit the area of the Western Sahara that is under Sahrawi control (outside of the camps) to find out about the local children’s rights situation. But it is certainly not easy to do research in such a vast and uninhabited desert!

18 January 2022 - Florentina Pircher & Marieke Hopman, Wesside Stories

After learning from children what according to them is the most important children’s rights issue in the camps, we now recruited and trained local researchers to help us to collect data from adults. This was our first time working with local researchers, which came with mostly learning opportunities and a few challenges.

11 January 2022 - Florentina Pircher & Marieke Hopman, Wesside Stories

What is it like, living in Sahrawi refugee camp? Spending some time in the Sahrawi refugee camps gave us an interesting look in the Sahrawi way of living. If you are also curious to find out how the Sahrawi refugees live their daily lives, watch this vlog!

21 December 2021 - Florentina Pircher & Marieke Hopman, Wesside Stories

In our research, we tried to find out what the main children’s rights issue is for children living in the Sahrawi refugee camps. After 10 interviews, some first findings and lessons can be shared.

23 November 2021 - Florentina Pircher & Marieke Hopman, Wesside Stories

We know that the Sahrawi live in refugee camps since 1976, but as researchers, we weren’t quite sure what to expect. What does a refugee camp look like, when people have been living there for such a long time? And will we be able to do our research?

27 October 2021 - Florentina Pircher & Marieke Hopman, Wesside Stories

This introductory vlog provides an overview of our research project on the rights of children living in the Western Sahara, a territory claimed by both Morocco and the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic. Since very little is known about the situation of children in the Western Sahara, the subsequent vlogs will present the findings of this field research.

By Tajra Smajic - 7 September 2021

Introduction

Fleeing from the conflict in Western Sahara in 1976, many indigenous Sahrawi nomads fled to the neighboring Algeria and settled near the Algerian town of Tindouf. Ever since, the refugee camps near Tinduf have been home to thousands of Sahrawi refugees and have been controlled by the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). While there is much to write about the history and life in the Tindouf camps, in this blog post, I will focus on the question on whether parents are allowed to lightly spank their children in the camps.

However, researching about children’s rights in ‘self-governing’ refugee centers, such as the Tindouf Refugee Camp, is not an easy task. These camps are governed by SADR, but it is neither recognized as a sovereign state nor can become a member to international conventions, such as the “Convention on the Rights of the Child” which prohibit any type of physical punishment of children. The answer of the question “what law is applicable and who is responsible in such areas in relation to the protection of children’s rights would not be straightforward. In this post, I will therefore look into different potentially applicable laws to find out whether parents are (legally) allowed to physically punish their children in the Tindouf refugee camps.

Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) law

Algeria, the host state of the Tindouf camp, delegated all responsibilities over the camps to the Polisario government. This means that in the camp, Sahrawi law is practiced. Leaving aside the issues that arise due to the lack of international recognition of SADR as a state and therefore the legality of its legislation, researching about children’s rights in the camp is accompanied with the difficulty of accessing the SADR legislation. While references to the Family Code, Civil Code and Criminal Code can be found, I was unable to access any of those sources and could base the legal analysis only on the Constitution.

Unsurprisingly, there is no provision in the constitution that prohibits physical punishment of children, especially not at home. However, some potentially relevant rules are:

- The family is the foundation of the society and should be based on religious, ethical and national values and on the historical heritage (Article7)

- The protection and promotion of the family values is the obligation of the parents, especially regarding the education of their children (Article 50)

- It is prohibited to violate anyone’s sense of morality or honour or to exert any kind of physical or moral violence against another or infringe their dignity (Article 28)

- Special protection is to be given to mothers, children, disabled persons and the elderly and the state has to set up institutions to that end and enact relevant laws (Article 39).

A map of the territory of Western Sahara and the Tindouf camps.

SOURCE: The Public Broadcast Service

At first sight, this could be understood to mean that physical punishment is not allowed, as it is prohibited to exert any kind of violence against another or infringe their dignity. Additionally, children are supposed to be under special protection. This reasoning would be in line with the international law. However, without being able to access the family or criminal codes, it is impossible to establish whether there is an explicit prohibition of physical punishment of children at home. Even if such a prohibition exists, the question remains whether such legislation is accessible to parents in the camps and if parents would be aware of such a prohibition.

International and regional law

As an unrecognized state, the SADR is not a party to international treaties such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child. It signed but did not ratify the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACRWC). Therefore, the statement of the African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, body responsible for supervising implementation of the ACRWC, which established that physical punishment is not allowed under ACRWC, has no legal effect in SADR. This means that under international and regional law, the SADR has no obligation to prohibit physical punishment at home.

Sharia law

Islam, as the predominant religion of the Sahrawi, plays an important role in the Tindouf camps. Moreover, according to the Sahrawi Constitution, Islam is the State religion and the main source of law (Article 2).

Sharia law (Islamic law) has multiple sources, namely the Holy Book (The Quran), the Sunnah (the traditions and practices of the Prophet Muhammad), Ijma' (opinions of Islamic scholars), and Qiyas (analogical reasoning based on principles deducted from the Qurʾān and the Sunnah). Due to the nature of these sources, the exact content is subject to interpretation. As a consequence of these different interpretations, there are divided views with respect to whether physical punishment of children at home is allowed.

Two main views are that (1) parents or guardians should refrain from physical punishment and use other disciplining methods instead, and (2) that physical punishment is allowed in certain instances. The second view is dominant and according to this interpretation of Sharia law, parents/guardians have to follow certain rules if they want to physically punish their child. I was able to identify following rules:

- The parent should use firstly other types of parenting methods, such as direction, kind warnings and advice.

- Children under the age of ten should not be beaten

- The punishment with beating should be appropriate to the misdeed

- The beating should not hurt the child either psychologically or physically

- Parents/guardians should beat only in a suitable setting, meaning not in front of other people.

- The child should not be beaten when the parent/guardian is angry. Both the parent and the child have to be aware that the beating is required for discipline, not for revenge or torture.

- The child should not be beaten in delicate places such as the face or private parts.

Nonetheless, not all rules are not always recognized with same importance and everywhere, and while some (such as the rule that parents have to use other means of upbringing first) are generally accepted, others are more disputed.

Algerian law

As Tindouf Refugee Camps are located within the Algerian borders, it is also important to consider Algerian law. Algeria ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and the African Charter on Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACRWC), both providing that physical punishment at home should be prohibited. According to Algerian Constitution, those conventions are superior to national law and can be invoked before national courts with superior authority to national legislation (Article 132 Algerian Constitution). This means that if national law is not in line with one of the conventions, the national court will set aside the national law and apply the Convention.

In 2015 the Algerian penal code was amended and some forms of domestic violence were prohibited. Some of those newly prohibited acts are:

- intentionally injuring or beating a minor under sixteen years,

- preventing the minor from food or care to the extent that the minor’s health is exposed to harm,

- or any other act of violence against a minor. (Article 296 Penal Code)

However, acts that cause ‘light harm’ and result from actions of parent’s methods of disciplining a child are not prohibited and are considered to be part of the parents' fulfilment of their responsibilities towards the child in raising it and correcting its behaviour. Therefore, actions such as light spanking, are allowed.

But what constitutes light harm? Where is the line to be drawn between physical punishment allowed to discipline the child and violence? The answer is: it depends. Several factors such as the age and maturity of the child as well as other surrounding circumstances have to be taken into account. Allowing acts of light harm gives courts and social care institutions flexibility to examine each case on its own merit. However, such a rule leaves a discrepancy between international law that Algeria is bound by, namely the CRC and the ACRWC, and national legislation.

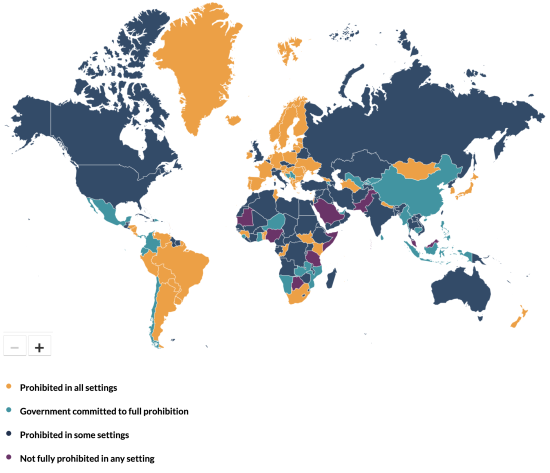

Corporal punishment per country

SOURCE: End Corporal Punishment. (2021). Detailed report on corporal punishment per country [Interactive map]. End Corporal Punishment.

Conclusion

Are parents legally allowed to physically punish their children in the Tindouf camp? While in situations where parents inflict serious harm by using physical punishment it is easy to establish that such punishment is considered violence against the child and is prohibited, when talking about acts such as light spanking the answer is ‘it depends’.

It is conditioned upon which law you think is most relevant. If you consider SADR law relevant, such punishment is allowed. However, given the important role Sharia law play, both in the Sahrawi population in the camp and under SADR law, it would seem that physical punishment is allowed only if certain rules are respected. On the other hand, if you believe Algerian law is applicable, physical punishment would seem to be allowed as long as it only causes light harm. However, as Algeria is bound by both CRC and ACRWC that prohibit any type of physical punishment, and as such international conventions have ‘priority’ over national law, it could also be understood that no physical punishment is allowed.

By Tajra Smajic - 10 August 2021

Introduction

When conducting our research on the rights of the children in the Tindouf camps, we encountered the question whether parents are (legally) allowed to physically punish their children.

One of the universal human rights of every person, including every child, is to be protected from violence. But does light spanking by parents to ‘teach a child a lesson’ qualify as violence? And if not, where is the line to be drawn between physical punishment of the child that is allowed and violence against the child? Or is physical punishment by parents not considered violence at all?

Disciplining a child can be difficult and parents opt for different methods of disciplining their children. One of the oldest methods thereof is physical punishment, which nonetheless is becoming subject to increasing criticism. But what is the legal view on physical punishment of children?

While in most countries physical punishment (also referred to as corporal punishment) in certain settings is illegal, such as in school, care centres and detention, the number of countries prohibiting such punishment at home is significantly lower. As it would be impossible to analyse the law of all states in this blog, the question whether parents are allowed to lightly spank their children will be examined in light of international and regional children’s rights law.

1. International children’s rights law

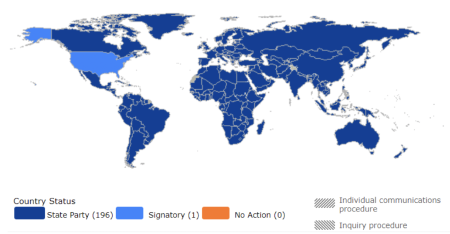

The most important international children’s right instrument is the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). All countries in the world except United States have signed and ratified this Convention.

According to the CRC, states need to:

- take measures to protect children from all forms of physical and mental violence (Article 19)

- take measures to abolish traditional practices that may harm the health of children (Article 24(3))

- ensure that disciplinary measures at school respect the child’s human dignity (Article 28(2))

- ensure that children are not subjected to torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (Article 37(a)).

State parties to the CRC

SOURCE: Human Rights Indicators Work. (n.d.). Ratification of 18 International Human Rights Treaties [Interactive map]. United Nations Human Rights.

However, the CRC is a living instrument, meaning that its content should be interpreted and adapted to changes and developments in the society. And, while it does not explicitly prohibit physical punishment of children, the Committee on the Rights of the Child (whose role is to monitor the implementation of the Convention) stated in General Comment No. 8 that the Convention requires states to prohibit and eliminate all corporal punishment, including in the home. This means that any punishment in which physical force is used and intended to cause some degree of pain or discomfort, however light, is prohibited. While the General Comment is not legally binding, it is an authoritative soft law document clarifying the obligations of States under the CRC.

Moreover, other important human rights bodies, such as the Human Rights Committee, the Committee Against Torture, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, all made recommendations to states to prohibit all physical punishment of children, including that at home.

2. Regional international children’s rights law

2.1 African Charter on the Welfare of the Child

Similar to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACRWC), ratified by 49 African states, aims at protecting children from violence. But does this include physical punishment?

The Charter requires states to undertake measures

- to protect children from all forms of torture, inhuman or degrading treatment and abuse (Article 16),

- to ensure that school’s or parental discipline respects the child’s inherent dignity (Article 15),

- to ensure to the maximum extent possible, the survival, protection and development of the child (Article 5).

The Charter does not only impose obligations on the states, but also on parents, who have to ensure that domestic discipline is exercised with humanity, and that it respects the dignity of the child (Article 20).

The African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, which supervises the implementation of the ACRWC, in their statement on violence against children, held that physical punishment of children should be publicly condemned and eradicated. They also require states to adopt laws that prohibit all corporal punishment of children in all settings including the home, and for states to put in place implementation measures to achieve effective protection of children. According to the committee, custom, tradition, religion or culture cannot justify harmful cultural practices such as physical punishment.

However, the implementation of such a prohibition varies across African countries, and while some have prohibited physical punishment of children in all settings including that at home (such as South Africa, Kenya, South Sudan and Tunisia) other countries have not fully prohibited physical punishment in any setting (such as Botswana, Tanzania, Mauritania and Nigeria).

Corporal punishment per country

SOURCE: End Corporal Punishment. (2021). Detailed report on corporal punishment per country [Interactive map]. End Corporal Punishment.

2.2 Europe

Unlike in Africa, in Europe there is no convention or charter specifically aimed at protecting children. This means that in European human rights law, there is no single provision that explicitly prohibits corporal punishment of children.

However, this does not mean that physical punishment of children at home is allowed. Why so? Children bear the same rights as adults under regional human right’s instruments; the European Convention on Human Rights and the European Social Charter are particularly relevant in this regard.

2.2.1. European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)

Physical punishment of children is not allowed under the ECHR, a convention that all European states are party to and that guarantees fundamental civil and political rights. This prohibition was developed through judgments in the legal cases of the European Court on Human Rights (ECtHR), which uses the ECHR. The Court first ruled on physical punishment in 1978, on a case concerning physical punishment at school: Tyrer v. the United Kingdom. In this case the Court ruled that such punishment is in breach of Article 3 of the ECHR which prohibits torture, inhuman and degrading treatment and punishment.

In 1998, the ECtHR for the first time addressed a case of physical punishment at home.

The case, A v. UK., was brought by a little boy who was hit with a cane by his stepfather. Initially, when the case was first discussed in national UK courts, the stepfather was under the defence of “reasonable chastisement”, and the national courts found that such physical punishment was allowed to discipline a ‘difficult child’. However, the ECtHR disagreed. They ruled that allowing for physical punishment at home was contrary to the prohibition on torture, inhuman and degrading treatment and punishment (Article 3 of the Convention), and concluded that this includes the prohibition of physical punishment of children in all instances.

However, a prohibition of physical punishment at home often encounters resistance in the society. Let’s take for example Sweden, which was the first country to prohibit physical punishment of children at home, already in 1977. The reaction to the ban was divided, and some parents believed that such ban interferes with their right to private and family life and freedom of religion. Some parents even brought the matter in front of the European Commission on Human Rights, the ECtHR predecessor. Nonetheless, the Commission found that such a ban neither interferes with the private and family life, nor freedom of religion, and held the case inadmissible. In such way, the Commission paved the way for other European states to implement a ban on physical punishment of children at home.

2.2.2 European Social Charter (ESC)

Physical punishment of children is also prohibited by the European Social Charter which guarantees fundamental social and economic rights and which applies to all European states.to which all European states are party to. Article 17 of the ESC requires states to protect children and young persons against negligence, violence or exploitation and encourage the full development of their personality and of their physical and mental capacities.

The Committee stated that states are required to create law that is sufficiently clear, binding and that specifies the prohibition of any form of violence against children, including physical punishment at home. (see this case).

2.3 Other regions

Outside of Africa and Europe there is no regional law prohibiting physical punishment.

While the Inter-American Court of Human Rights rejected the request by Inter-American commission on Human Rights to issue an advisory opinion on physical punishment of children, the Court did argue that “children have rights and are an object of protection”, that they have the same rights as all human beings, that the state must protect these rights in the private as well as the public sphere, and that this requires legislative as well as other measures.

While not binding, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights issued a Report on Corporal Punishment and Human Rights of Children and Adolescents recommending states to prohibit all physical punishment of children, including that at home.

In North America, physical punishment of children remains legal. However, in Latin America most countries have specific legislation prohibiting such punishment, at home including Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Costa Rica, Honduras, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela.

In Asia, there is no regional law concerned with physical punishment of children, and whether physical punishment of children at home is allowed, depends on the national law of different Asian countries.

3. Conclusion

Is it allowed to physically punish your child? Under international and, where applicable, regional children’s rights law, the answer would be no. Such punishment, regardless of how light or severe, is illegal according to the Convention on the Rights of the Child and regional instruments such as the African Charter on the Welfare of the Child or the European Convection on Human Rights. However, this legal prohibition on the international level is not always reflected in national laws. Sometimes it is even contradicted by national laws explicitly allowing for physical punishment of children. Therefore, in reality the legal situation remains different due to the discrepancies existing across different national laws.

If you are interested in what this means when talking about unrecognized states, look into our next blogpost where we will examine whether parents are allowed to use physical punishment as a way of disciplining their children in the Tindouf refugee camps.

By Victoria van Heesewijk - 20 July 2021

In February 2020, researchers Marieke and Florentina visited the Sahrawi refugee camps in Tindouf, Algeria for the first time and started a case study on the child’s right to live free from any form of violence. Subsequently, many different people were involved in the study including a group of students. In this video, MaRBLe student Victoria will introduce you to the research process and research methods of investigating this right in the camps.