Right to education in the Netherlands

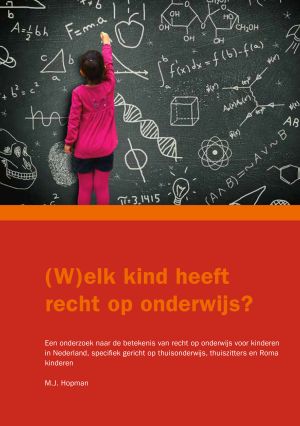

In 2016 researcher Marieke Hopman conducted a study on the child’s right to education in the Netherlands, with a specific focus on children out of school, homeschool and Roma children. The study results were published in chapter 5 of her PhD and in a Dutch language report (W)elk kind heeft recht op onderwijs?. Below you find the blogs and vlogs she created to share her experiences and reflections during the research process, from the first to the latest. Please note that some of this content is available only in Dutch.

By Marieke Hopman - 17 October 2016

This interview in VOS/ABB magazine, on the previous case study (right to education in the Netherlands), came out last week. Title: "Without social interaction it can't be done". Subtitle: "Social interaction is crucial for a healthy development of children, emphasizes legal philosopher Marieke Hopman. Therefore she posits that homeschooling in principle is harmful and schools should do more with social interaction".

Interestingly, they asked a homeschooler (mother) to reply. She argues that firstly the primary goal of education is knowledge and cultural education, not socialization. Secondly, socialization can happen through the village, the church, the family, which - in apparent contrast to schools - are not "child reservations".

By Marieke Hopman - 19 June 2016

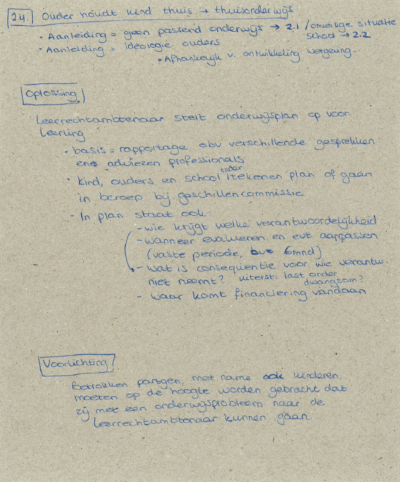

Eén van de belangrijke aanbevelingen van mijn onderzoek "(W)elk kind heeft recht op onderwijs?" is dat het een goed idee zou zijn om in elke gemeente een leerrechtambtenaar aan te stellen. Momenteel heeft elke gemeente een "leerplichtambtenaar", mijn voorstel is om deze ambtenaar een andere functie, met een andere focus te geven.

Functieverandering leerplichtambtenaar

Momenteel is onder de huidige leerplichtwet de opdracht van de leerplichtambtenaar met name gericht op het zorgen dat ouders hun kinderen naar school sturen. Deze opdracht stamt nog uit het begin van de vorige eeuw, toen het nog gebruikelijk was dat kinderen werkten om het gezin van inkomen te voorzien, met name fabriekswerk.

Uit mijn onderzoek blijkt dat er momenteel een centraal punt ontbreekt waar kinderen, ouders en professionals naartoe kunnen zodra de verschillende beslissers geen antwoord kunnen vinden op de vraag: wat is het beste (passende) onderwijs voor dit kind? In de praktijk zie je nu dat het met name in deze situatie is, dat een kind thuis komt te zitten.

De leerrechtambtenaar: hoe werkt het in de praktijk?

Op het moment dat er iets misloopt kunnen scholen, ouders en/of leerlingen zich melden bij de leerrechtambtenaar. Deze gaat dan op zoek naar een oplossing, in overleg met de betrokken partijen. Hij zal in veel gevallen ook advies bij professionals moeten inwinnen, zoals bijvoorbeeld van een arts (jeugdarts, pedagoog, psycholoog), het samenwerkingsverband, de onderwijsconsulent, de onderwijsinspectie en/of jeugdzorg – afhankelijk van de situatie.

Hieronder heb ik een voorstel geschetst voor hoe dit er concreet uit zou kunnen zien. Ik hoor heel graag hoe jullie hier over denken!

Ouder, kind en leerkracht/bestuur school kunnen dus alle drie onafhankelijk de hulp van de leerrechtambtenaar inschakelen, wanneer er een probleem is rondom het recht van het kind op onderwijs. Er zijn dan vier mogelijke situaties die aanleiding geven voor een gesprek (maar wellicht ontbreekt er nog iets in dit lijstje):

2.1 er is geen passend onderwijs op school;

2.2 kind wil niet naar school i.v.m. onveilige situatie (pesten o.i.d.);

2.3 ouder houdt kind thuis zonder onderwijs;

2.4 ouder houd kind thuis -> thuisonderwijs

Misschien dat "kind wil niet naar school om andere reden" moet worden toegevoegd. Vervolgens gaat de leerrechtambtenaar met de verschillende partijen in gesprek en stelt hij/zij een plan op, wat door alle partijen ondertekend moet worden. Partijen kunnen eventueel in beroep als zij het niet met de beslissing van de leerrechtambtenaar eens zijn, bij de geschillencommissie passend onderwijs.

Het voordeel van de gemeentelijke leerrechtambtenaar is dat de lijntjes kort zijn met alle partijen, waardoor het relatief makkelijk is om partijen op kantoor uit te nodigen. Ook heeft hij/zij korte lijntjes tot financiering op gemeentelijk niveau (bv. leerlingenvervoer) en deze ambtenaar heeft de juridische positie en het gezag om verschillende partijen (school, ouders, kind) op hun verantwoordelijkheid aan te spreken, mochten ze echt niet mee willen werken.

Leerplichtambtenaar wordt leerrechtambtenaar: maakt dat echt uit?

In zijn antwoord op kamervragen over dit onderzoek schrijft staatssecretaris Sander Dekker dat

'De belangrijkste missie van de leerplichtambtenaar is ervoor zorgen dat kinderen hun recht op onderwijs verzilveren. De leerplichtambtenaar fungeert daarmee in de praktijk reeds als ‘leerrechtambtenaar’, die het belang van het kind en het recht op onderwijs centraal stelt'.

Uit dit onderzoek blijkt echter dat dit niet het geval is; leerplichtambtenaren geven zelf aan dat ze vooral gericht zijn op het verplichten van de ouder om hun kind naar school te sturen, en daarbij eventueel juridische stappen te ondernemen. Tegenover scholen hebben ze weinig te zeggen, dus wanneer een school weigert passend onderwijs te bieden en het samenwerkingsverband besluit om het kind elders te plaatsen terwijl dat niet noodzakelijk is, bijvoorbeeld, staat leerplicht met lege handen. Bovendien hebben kinderen zelf niet het idee dat zij een recht op onderwijs hebben en dat zij dit recht ook af kunnen dwingen. Kinderen zeiden allemaal: "Recht op onderwijs? Het is alleen maar je moet, je moet, je moet!"

In een uitzending op radio 1 van maandag 13 juni zegt Dekker:

'Alle kinderen in Nederland hebben recht op onderwijs, dus dat leerrecht dat bestaat in mijn ogen. En nou, een leerplichtambtenaar kunnen we omdopen tot een leerrechtambtenaar, ik weet niet of dat een semantisch iets is wat onmiddelijk tot een oplossing gaat leiden'.

Deze twijfel is volkomen begrijpelijk, want wat maakt het nou uit hoe we de functie noemen? Toch denk ik dat we de kracht van woorden niet moeten onderschatten, zeker ook in deze discussie. Een leerrechtambtenaar zou er door zijn of haar functienaam alleen al elke dag aan herinnerd worden wat de centrale focus van zijn of haar opdracht is: het recht van kinderen op onderwijs realiseren. Dit geldt niet alleen voor de ambtenaar zelf, maar ook voor alle partijen er omheen. Hoe te gek is het, als jij als kind zelf weet: als mijn school mij niet het onderwijs geeft waar ik recht op heb, dan kan ik op de fiets naar het gemeentehuis en daar in gesprek met de leerrechtambtenaar. De leerrechtambtenaar komt op voor mijn recht op onderwijs!

Semantiek maakt zo veel uit, de woorden die we gebruiken sturen hoe mensen denken. Daarom hebben we ook zulke heftige discussies over het gebruik van woorden als zwarte piet, negerzoenen, marokkaantjes, allochtonen...

Toch lijkt Dekker het voorstel inhoudelijk wel te steunen, al twijfelt hij nog over de naamsverandering. Hij eindigt het interview met:

'Wat ik heel erg belangrijk vind, is dat uiteindelijk in iedere gemeente iemand is die met de vuist op tafel kan slaan als zorginstellingen en scholen er te lang over doen om een goede plek te voorzien. Dat noemen we [...] doorzettingsmacht'.

Hoe nu verder?

Op 29 juni a.s. debattert de commissie OCW over passend onderwijs. Van 10.00-15.00 wordt o.a. de voortgangsrapportage passend onderwijs gesproken, waarin ook op bovenstaande punten verder zal worden ingegaan.

Zelf ben ik door verschillende gemeenten en andere organisaties die zich bezig houden met het recht van kinderen op onderwijs, uitgenodigd om mee te denken over het realiseren van dit recht. Het bovenstaande voorstel wordt daarbij dus ook meegenomen door verschillende gemeenten. Aanpassingen/aanvullingen zijn dus zeer welkom!

By Marieke Hopman - 14 June 2016

Today I taught my second lesson of philosophy in a Danish public school. I teach two very different groups, and my story today is about the first group. They are a 7th grade class, all 13-14 year old boys and girls.

In Denmark, compared to the Netherlands, the authoritative structure of the school is quite loose. For example, classes are scheduled to start at 8 am. However, it seems like most don't start before 8.15 - amongst others because teachers are late - and until about 8.30 students are arriving. In the Netherlands on the other hand, if you are 1min late your name is registered, if you come late twice it means two hours of cleaning duty. Another Danish example is that apparently it is quite normal for students to decide they want to work elsewhere but in the classroom and to simply leave the classroom without saying anything. So far I have several times lost some of the students and I have to search them in the school, because otherwise I can't help them with their work.

Yesterday the students chose questions they found interesting and today they got assignments and texts to philosophically examine these questions. The questions are: A) How do we know that we do not live in a game?; B) What is time?; C) Morality: how can we solve a moral dilemma?

In the 7th grade there is one boy, let's call him Max. Max is very hard to handle. He is not necessarily unkind, but he simply does not participate in class activity. Obviously I don't know him very well, but it seems like he is quite unhappy, restless and not motivated to learn anything. Yesterday he was spending most of his time either walking around the classroom touching some of the other boys - mostly holding his arm around their neck and pushing them down -, sleeping on his desk or he was just gone from the classroom altogether.

So this morning I started the day by asking him what he wants, what he needs to learn, what he likes, what he finds interesting, what he needs from me. He said that in fact he thought the class was interesting and when I asked him why he did not participate, he said that he did and in fact for a moment started discussing the question of the moment (Matrix: would you take the red or the blue pill?). However, quite soon after, his interest or concentration or whatever was gone again.

When later in the afternoon I offered to read a part of Plato's The Republic with him and two of his friends, his friends were willing and we started reading together. He first came and sat with us without his text. His friends told him to go and get his paper. He walked back grudgingly, got the paper, dropped it on the floor a bit further, said something in Danish and walked away. When I asked what he had said his two friends shrugged their shoulders and said that he was just going. They wanted to read the text. When I suggested to wait for Max they said they would rather not, because Max wasn't interested in learning anything. So they would rather read without him (and these were not very serious, hard studying boys).

When later I asked the other teachers about Max, they said that it was a school problem. They didn't know what to do with him. Danish education is inclusive; the idea is that all children, no matter their background, religion, behavior, iq level, etc. are welcome. In this way the class represents regular society. But what to do with a boy like Max, when you have 25 other students that need your attention? The answer in practice, apparently, is: you give him the freedom to leave the classroom whenever he wants. It is a problem, the teachers admitted. They did try to get the boy psychological help, he has been out of school for 1,5 years, he has been in a special school for a while.

I am at a loss here. I don't know what to do with this boy. He has a right to education and I want to teach him. But I cannot sit next to him all the time if I also have to teach 24 other students - even if I would love to and I think it would help him. It would not be fair to the other students. But this means that Max plays around in the classroom or walks away, and in either way he is not getting any education...

By Marieke Hopman - 12 June 2016

Dear all,

The coming week I will be teaching philosophy in Denmark, and I intend to write about it on this blog. I will be teaching 13-15 year olds, who are in regular school in a village called Hundested. Coming from the Netherlands, I am curious to see the education system from more of an insider perspective!

For now, I have already noticed that the organization aspect is quite different from what I am used to. In the Netherlands, if I would come to a school as a guest teacher (especially for this age category), everything would be arranged in detail a few weeks or more before the course starts. In Denmark on the other hand, up until last friday I did not even know who I was going to teach exactly and it was mostly because I was in the school to do some printing and ran into some of the teachers that I found out that I will have two groups; the local-global class from 8.00-11.00 and a selection of three students who have the best level in English of their class from 12.00-15.00 (although I am not exactly sure about these times either).

I have been enthusiastic about the flexibility of the Danish curriculum before, however experiencing this flexibility from up close like this has been challenging for me (and quite an insightful confrontation with myself too), as I usually like to be well-prepared. It is an exercise in letting go, and just go with the flow!

On the social side, which I was equally enthusiastic about before as being so important in Danish education, I got to experience this right away firsthand. Everyone has been incredibly friendly and open, willing to help with anything I need, coming over for drinks and inviting me to social events (most notably last friday's teacher's party). One of the teachers is allowing me to stay in her wonderful summer cottage (pictures below), and I feel so lucky and blessed to be here.

Tomorrow I will start the first class, so let's hope all goes well...

By Marieke Hopman - 7 June 2016

Vandaag was ik te gast bij de particuliere school "Maupertuus" in Driebergen. Op deze school worden al sinds 27 jaar kinderen opgevangen die uit het regulier schoolsysteem vallen, of dreigen te vallen. Het gaat om kinderen met verschillende en vaak gecombineerde problematiek; een mentale beperking, een fysieke beperking, een psychiatrische ziekte ... in feite zijn alle kinderen welkom, zolang ze maar niet agressief zijn tegen andere kinderen. Een veilige, warme omgeving is een belangrijk speerpunt van de school.

inderen krijgen op Maupertuus een intensief pakket aangeboden, een combinatie van geïntegreerde zorg en onderwijs. Voor elke leerling die binnenkomt wordt door het team, bestaande uit leraren, psychologen, pedagogen, logopedisten, ergotherapeuten en fysiotherapeuten een persoonlijk plan opgesteld, in overleg met ouders en het kind zelf. Zo krijgt elk kind een eigen pakketje maatwerk. De kinderen die hier binnenkomen hebben vaak al veel meegemaakt en zijn daardoor zwaar beschadigd geraakt. Zo'n maatwerk pakketje is dan ook geen overbodige luxe, sterker nog: het is een noodzakelijke voorwaarde om de kinderen weer op de rails, en stapje voor stapje terug in het reguliere onderwijs te krijgen. Want dat is het doel: bij Maupertuus worden kinderen begeleid zodat zij terug kunnen keren in de reguliere maatschappij. En dat werkt, zoals je o.a. kunt lezen op deze blog door een oud-leerling!

Er zijn helaas wel twee grote nadelen aan Maupertuus: ten eerste het financiële plaatje, ten tweede de reikwijdte.

Ten eerste het financiële plaatje. Een jaar Maupertuus kost per kind zo ongeveer € 23.000 per jaar. Omdat het een particuliere instelling is, moet dit door ouders worden betaald, en uiteraard kan niet iedereen zich dat veroorloven. Ondanks vele pogingen om van overheidswege geld te krijgen voor het opvangen van beschadigde leerlingen, is dat tot nu toe niet gelukt. Ook kan de school zich niet aansluiten bij het samenwerkingsverband - ze werken wel samen met andere scholen, maar kunnen geen financiering krijgen. En denk vooral niet dat dit bedrag zo hoog is omdat de medewerkers er rijk van worden: een leraar op Maupertuus verdient minder dan een docent in het regulier onderwijs.

De schoolleiding zet zich in om ook kinderen van minder rijke ouders een plek te kunnen bieden indien nodig. Daarom was vandaag de start van de actie "Maupertuus helpt thuiszitters". Maupertuus stelt volgend schoojaar 5 plekken beschikbaar voor thuiszitters, kinderen die al langere tijd niet naar school kunnen omdat er voor hen geen passend onderwijs is. Hiervoor moet alleen nog € 80.000 worden ingezameld. Vandaag waren de leerlingen daarom druk in de weer met het verkopen van zefgemaakte soesjes, taart, patat, tomatenplanten, koffie en thee. De opbrengst hiervan gaat naar de actie. Eind juni volgt er nog een benefietdiner waar hopelijk de rest van het benodigde bedrag wordt opgehaald.

Het tweede nadeel van Maupertuus is het beperkte bereik van de school. De school staat namelijk in Driebergen, en ze zijn naar eigen zeggen de enige onderwijsinstelling in Nederland die volgens deze formule een combinatie van zorg en onderwijs aanbiedt. Ze hebben, vanwege de kleine klassen e.d., maar beperkt plaats: er kunnen maximaal 120 leerlingen naar Maupertuus. En die komen nu al van heinde en verre (zo heb ik er twee ontmoet die uit Amsterdam kwamen). In Nederland zijn er veel meer kinderen die een jaar Maupertuus zouden kunnen gebruiken. Waar moeten zij heen?

Uiteraard kunnen met zo'n kostenplaatje niet alle kinderen deze zorgintensieve vorm van onderwijs volgen. Maar ten eerste zijn er gelukkig relatief weinig kinderen die dit nodig hebben, en ten tweede, als we naar de lange termijn kijken, levert deze vorm van onderwijs juist geld op. Deze kinderen staan op de lijst om hun hele leven in een instelling door te brengen. Zij bevinden zich op zo'n cruciaal punt in hun ontwikkeling en dreigen uit te vallen, in zodanig ernstige mate dat zij misschien wel nooit meer zullen integreren in de reguliere maatschappij. Als instellingen zoals Maupertuus de kans krijgen om deze kinderen zó te kunnen begeleiden dat zij toch weer in de maatschappij mee kunnen draaien: dan is dat een winst in alle mogelijke toonaarden. Niet alleen voor de kinderen zelf, maar voor alle Nederlanders.

Wie bij wil dragen aan de actie van Maupertuus kan een donatie overmaken naar Stichting Reynaerde, NL16RABO 0385281730, onder vermelding van MAUPERTHUIS.

By Marieke Hopman - 27 May 2016

26 mei 2016

- Thuisonderwijs. Onderwijs dat thuis door ouders of externe docenten wordt gegeven, heeft voor kinderen voor- en nadelen. In sommige gevallen kunnen kinderen niet naar school en dan kan thuisonderwijs een goede oplossing zijn. De kinderen komen echter vaak achter te lopen op het gebied van sociale vaardigheden en relaties, zeker in relatie tot leeftijdsgenoten.

- Thuiszitters. Thuiszitters zijn kinderen die uitvallen uit het schoolsysteem, door een keuze van de ouders of van de school. Van deze kinderen krijgt een deel thuisonderwijs en een deel krijgt geen onderwijs. Deze situatie ontstaat meestal door een conflict tussen school en ouders.

- Roma kinderen. Een relatief groot deel van de Roma kinderen gaat niet naar school of volgt alleen primair onderwijs. Oorzaken zijn een combinatie van discriminatie door scholen, overheid en de maatschappij in het algemeen, desinteresse of andere toekomstverwachtingen van ouders.

Marieke Hopman, auteur van het rapport en promovendus Tilburg University: "Thuisonderwijs of thuis zitten zonder onderwijs is in principe schadelijk voor de ontwikkeling en het welzijn van het kind. Uit vrijwel alle gesprekken met de kinderen blijkt dat het ontwikkelen van sociale vaardigheden, met name in relatie tot leeftijdsgenoten, ontzettend belangrijk is."

Jan Pronk, oud-minister en adviseur promotieonderzoek: "Alle kinderen hebben recht op onderwijs dat voorbereidt op een leven in onze gecompliceerde maatschappij. Dus niet alleen kinderen zonder beperking, of kinderen met de juiste etniciteit, maar alle kinderen in Nederland. Het is de hoogste tijd dat de overheid zijn taak, om dit recht te garanderen, serieus op gaat pakken."

Wanneer het recht van kinderen op onderwijs wordt geschonden, zou er een centrale partij moeten zijn die conflicten tussen verschillende beslissers op kan lossen en daarbij het belang van het kind centraal stelt. De suggestie die daarvoor in dit rapport is gedaan, is het aanstellen van een gemeentelijke leerrechtambtenaar.

Aloys van Rest, directeur van Defence for Children: "In Nederland zitten duizenden kinderen thuis, terwijl ze recht hebben op onderwijs. Dit is een schending van de kinderrechten en dit gaat in tegen internationale afspraken. Zoals ook de kinderen in het rapport aangeven zou er een verschuiving moeten plaatsvinden van een 'plicht op onderwijs' naar een 'recht op onderwijs'. Zo stel je het belang van het kind in het onderwijs centraal, iets waarvan dit rapport duidelijk laat zien dat dit nodig is."

Naar aanleiding van het rapport heeft Ypma (PvdA) aan de staatssecretaris van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap Kamervragen gesteld.

IMAGE: Thuiszitters Rebecca en Sebastiaan reiken eerste exemplaar van het rapport uit aan leden van het expert panel: Jet ten Brinke (onderwijsinspectie), Paul Zoontjens (prof. onderwijsrecht TiU) en Paul van Meenen (Twee Kamer lid commissie onderwijs, D66).

SOURCE: Defence for Children/Daniella van Bergen.

By Marieke Hopman - 19 May 2016

By Marieke Hopman - 17 May 2016

Dear all,

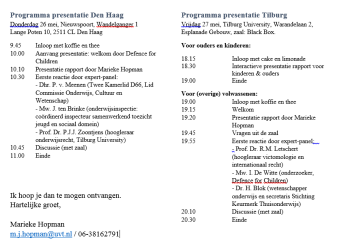

I have finished my research report on the right to education in the Netherlands! It will be presented twice (!!); on May 26 in the Hague, on May 27 at Tilburg University. There is a wonderful expert panel on each location, and I think it will be a wonderful event. If you would like to attend, please email me at

Hope to see you there!

Here's the program:

By Marieke Hopman - 16 May 2016

Voor mijn deelonderzoek naar het recht op onderwijs van kinderen in Nederland, heb ik een aantal Nederlandse rechtszaken m.b.t. recht op onderwijs, en een aantal uitspraken van de geschillencommissie passend onderwijs op een rijtje gezet. Voor wie deze wil bestuderen, publiceer ik deze schema's (al zijn ze redelijk schetsmatig) hieronder:

By Marieke Hopman - 12 April 2016

Principal Malene Nyenstad, who is the head of a regular Danish public school, explains the basic philosophy of the Danish educational system. She explains that for the Danish, the most important goal of education is to learn social skills. It is considered both a condition for learning subjects because they 'believe that it is impossible to learn if you can’t manage your social life', and one of the most important learning goals in life. As Malene says: 'Of course it is also very important that they know how to read and how to do math, and how to speak English [...] but if you don't know how to relate to other people, then the rest doesn't matter'.

By Marieke Hopman - 9 April 2016

The Sputnik school is the result of an experiment of the local government of Copenhagen. Nine years ago they started a project to realize the right to education for several children who had dropped out of school and for whom there was no good alternative. These are young people with very serious mental issues, who might otherwise be in a mental hospital.

In the location we saw, they educate the children who are more introvert (suffering from depression, schizophrenia, anxiety disorder, etc). There is another location where they educate the children who are more extrovert.

The facilty is open to children age 13-17. There is one teacher for every three students. Each teacher picks three students who are then his "favorite people". The teachers function as teachers, social workers and therapist in one, in addition to regular external support.

The 32 students all have a personal space in a small shared room, such as you see above. Teaching and therapy take place in informal settings.

The facility is expensive (about € 5000 per month), but very effective; in the end many of the children find their way into the regular education system and/or into employment. The key to the success is the flexibility of the teacher and the school system. One of the things that works is that they have a car service and go to great lengths to get the children to school and create a safe environment. If necessary, they visit the house of a child who has been signed up. The child might hide under the blanket in its room. The teachers they will just sit on the bed and say "we are staying 10 minutes today". Then they come back the next day and stay for 15 minutes etc, until the children are ready to go to school. Another child who could not learn in a group setting was taught by a teacher in a car for 6 months.

Their idea is that these children have already been forced to do all sorts of things in the school system and this is part of the reason why they dropped out. One of the most important goal of the facility is to stress down these children.

The Sputnik school is where these drop-outs get a new start. The teachers take children by the hand and create new narratives (such as "I can see you are a fighter"). Very rarely they find that they cannot work with some children. They live by the rule that "we can't expel children for a reason that we knew already when we decided to accept the student in the school".

Financially, Sputnik is a private educational institution. Children who are signed up are paid for by the local government, on the basis of a year contract. Even though it is an expensive facility, they argue that on the long term it saves money as they invest in children who would otherwise never contribute to society.

By Marieke Hopman - 8 April 2016

Today one of the things we were shown was a regular primary school. In Denmark the classes have a maximum of 27 (or sometimes 28) students. Since some years now the policy is based on inclusion; they try to keep all children with any kind of problems in school.

To this purpose, at this school they have "period classes", or "p-class". The space they work in is just a classroom in the regular school. When there are children with externalizing problems (anti social or agressive behavior etc), they can go to this special class. There are 11 students currently, two teachers and a social worker.

Some students are there for a few months and slowly re-integrate into their regular classes, some children are there for years and might only follow gymnastics for example with their regular class. On the left you see some of the kids working on a group assignment (the older kids help the younger kids).

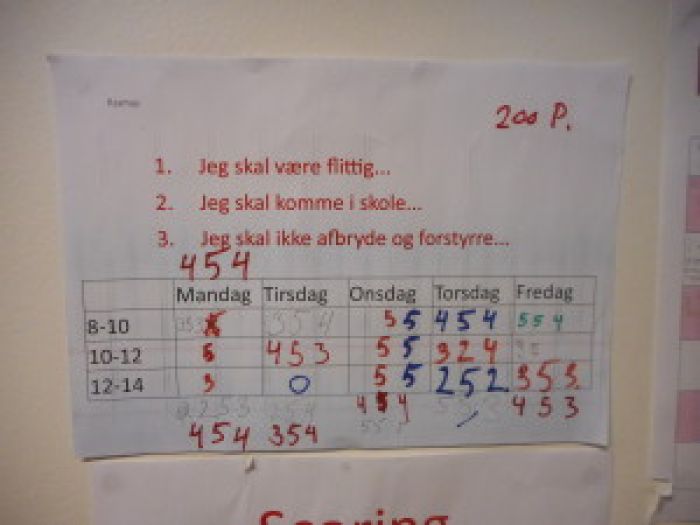

The children create their personal learning schemes on which together with their teachers they set up personal goals. On the right you see one of these forms. This boy, Rasmus, has three goals:

1. work conscientiously every day

2. come to school every day

3. not to distract other pupils

Every day at the end of the day he and his teacher will evaluate whether he reached his goals. He will get a score between 0-5. As soon as he reaches 200 points they celebrate and he can pick a reward, such as having 2 hours of football matches outside.

I thought this was a very ingenious and positive system for encouragement and making school fun, especially for children with personal, social or learning problems. Another teacher explained that in her higher class sometimes a student is misbehaving for some time, and she will go and say "I have to score you now". They work with the same system, and it makes students feel a little embarrassed because it is considered childish. They then get 5's every day.

Another thing that I thought was very interesting, is their playground. It looks very nice, spacey and natural. They told me that actually the design was a democratic process, where they let children participate in the decision how the playground should look. While the adults wanted to have only sand, the children suggested to have some concrete places so that they could play there with a ball. And so they did.

By Marieke Hopman - 7 April 2016

An Erasmus+ program offered me a last minute chance to join a study trip to Denmark to learn about the Danish educational system. I am especially interested in the solutions they have for inclusion/ exclusion of pupils.

Today we visited a production school. This is a special facility where students between age 15-25, who are "school tired" (meaning they are having a hard time staying in school for different reasons, such as low IQ, difficult family situation, psychological problems, etc) can go. They follow practical education for maximum one year, where they work on (in this order):

1. personal development

2. social development

3. practical/technical skills

The main goal of the program is for them to find an answer to the question "what is the way for me?". They get help getting their life on track.

How does it work? There are several workshops, which you can see below. They perform work, in part for customers. The financial model involves in part government funding, in part profit from the work that is done. Students are payed about € 1 per hour for the work they do.

On the left image there's a little part of the "pedagogical workshop" where students are training to work on creative things with children (for example in daycare), to do hairdressing, sewing and art. In the middle you see the music studio where students learn to make music together and record their music, sometimes working with local bands. On the right you see one of the school's bands. Because they have only been together for a short time I did not expect them to be so good but they were!! They make money by performing during parties, school parties, etc.

In the woodworkshop students train to be carpenters and do woodworking. They are hired by local companies for production work. The house below is a house they are currently building.

In the garage students do mechanical work on cars. Local people bring their cars in that need reparation. One of the Danish teachers accompanying us said he brought his car in recently and it still works well :-).

In the television workshop they produce 2 hours of tv material per week, for the local television network. They use professional equipment and are paid, as long as they reach a minimum amount of viewers of 15.000 per month. Luckily, they have 30.000 and another 20.000 online per month.

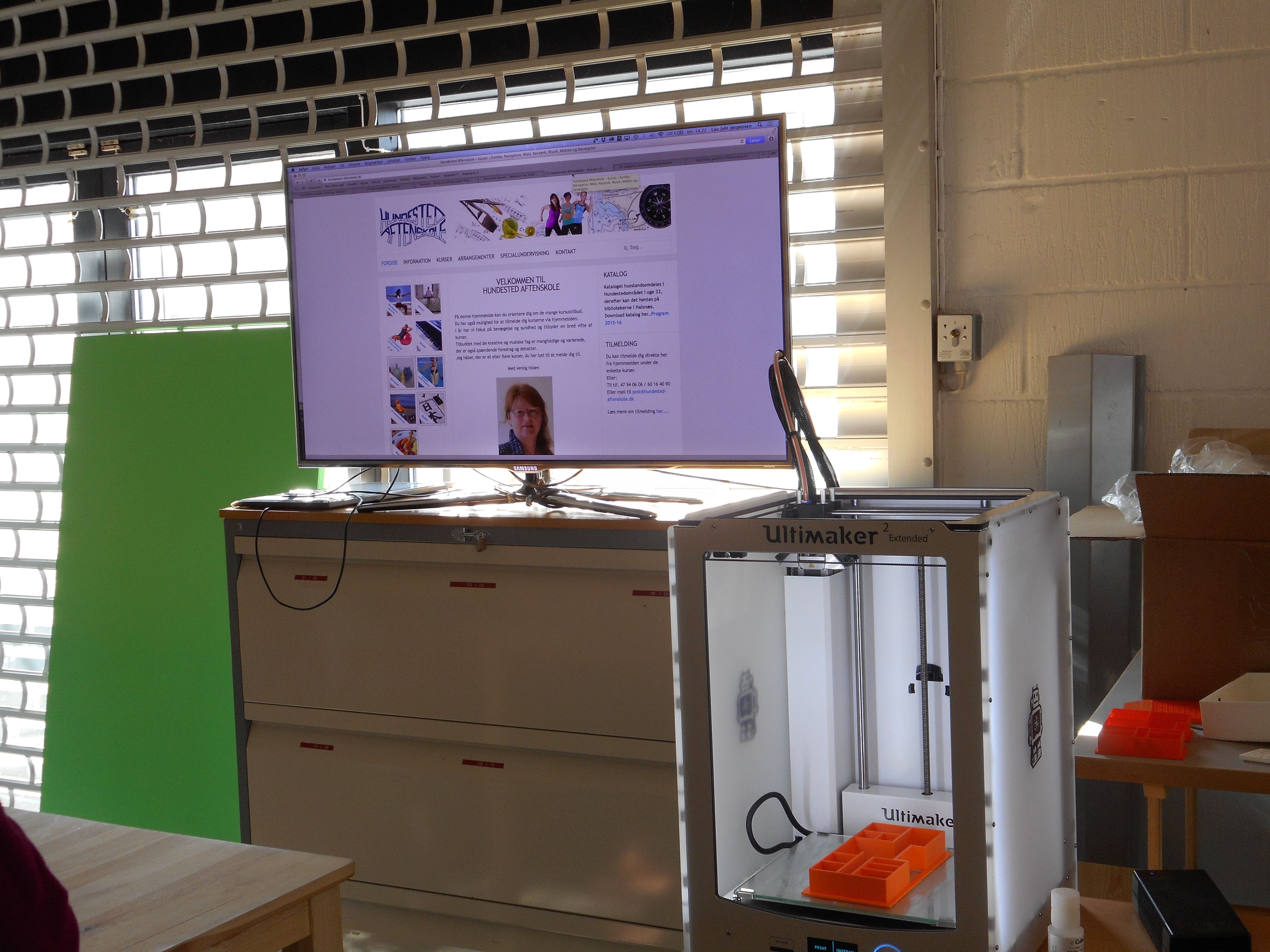

In the IT workshop, students learn programming, building websites and 3d printing. Yearly, they create about 10 websites for companies or individuals.

Lastly the kitchen workshop. Here students learn to cook etc. We had cake and coffee that they had prepared. Every day they provide breakfast and lunch for the 100 students in the school.

All in all it seems like it is a successful project - students find fun again in learning. They build confidence (many come from broken homes and very negative social and educational experience). Whenever they start, they start by setting personal development goals with a counselor. They might work on building confidence, being less shy, learning to be on time in the morning - even though they have a drug problem, etc.

Internal research shows that students are happy in the school and there is NO bullying, which is amazing seeing the selection of students and their backgrounds. I spoke to quite a few students - whose level of English was amazingly high - and they were very friendly, happy to show their work and explain what they were doing. They all said how much they liked the school.

On the downside: what happens to these students when the year is over? The school counselor spoke about how hard it is to find a subsequent placement for these children. The requirements for technical educational programs are sometimes linked to high school grades, which these students sometimes don't have. There is a shortage of work and so they cannot always start to work. However a teacher mentioned that about 75% of the students continue into further education.

By Marieke Hopman - 28 March 2016

- I have now started to plunge myself into the (academic) literature about social skills and group dynamics in education. If anyone wants to learn about it, I greatly recommend reading "Best Friends, Worst Enemies", a wonderful and very accessible book by dr. Michael Thompson (a child psychologist working in educational contexts on exactly this subject).

By Marieke Hopman - 17 March 2016

Gitseren heeft de commissie OCW gedebatteerd over thuisonderwijs. Momenteel is thuisonderwijs niet toegestaan, tenzij ouders ontheffing hebben van de leerplicht vanwege geloofsbezwaren met betrekking tot regulier onderwijs. Sterker nog: ouders die momenteel via deze weg ontheffing van leerplicht krijgen (leerplichtwet 5b), hoeven helemaal geen onderwijs te geven aan hun kinderen, er is geen enkele controle op wat er met deze kinderen gebeurt.

Je begrijpt waarom men hier verandering in wil brengen.

In de praktijk wordt er geschat dat er momenteel 617 kinderen thuis onderwezen worden in Nederland.

Het debat was heftig en zeer boeiend. Wat mij vooral interesseerde was dat het een discussie was over welke juridische norm de bovenhand zal voeren. Is het recht van educatie het recht van het kind, en moet die daarom meebepalen hoe zijn/haar onderwijs eruit ziet? Of is het kind het eigendom van de ouder, en mogen ouders daarom kiezen welke vorm van onderwijs kinderen krijgen (wellicht onder bepaalde voorwaarden met een onderwijsinspectie die thuisonderwijs controleert)? Of zijn kinderen van de staat en moeten ze daarom "gewoon" naar school?

Zo zei dhr. Bruins (CU), bijvoorbeeld dat er in de discussie twee grondrechten botsen: ‘het recht van het kind op onderwijs en de schoolplicht enerzijds, en het recht van ouders om primair te kiezen voor de opvoeding en het onderwijs dat hun kind krijgt’. Hij meent dat wanneer ouders op deugdelijke manier onderwijs geven thuis, dit niet onmogelijk moet worden gemaakt. van Meenen (D66) argumenteerde echter als volgt: 'recht op onderwijs, dat komt in mijn ogen het kind toe. Niet de ouder, niet wie dan ook, maar het kind'. Straus (VVD) sprak ook over twee rechten; de vrijheid van onderwijs, wat bestaat uit keuzevrijheid van ouders, en het recht van kinderen op goed onderwijs. Door thuisonderwijs af te schaffen zouden we vrijheid in onderwijs verliezen. Daarom wil zij thuisonderwijs toestaan, maar als uitzondering; de norm blijft dat kinderen naar school gaan. Hierbij gaf v. Dijk (SP) weer aan dat het formaliseren van thuisonderwijs wellicht een aanzuigende werking zal hebben.

Staatssecretaris Dekker lijkt in zijn beantwoording te zoeken naar een middenpositie in het debat; aan de ene kant zegt hij dat een kind het beste tot zijn recht komt in de sociale omgeving van de school, met onderwijzers die daar een opleiding voor hebben gevolgd. ‘In sommige situaties is schoolonderwijs echter niet mogelijk of wenselijk, volgens de ouders, en dan loopt het recht van kinderen op goed onderwijs gevaar. Daarom wil ik thuisonderwijs als een volwaardige vorm van onderwijs naast het schoolonderwijs wettelijk mogelijk maken, en dat zou dan mogelijk moeten zijn voor alle ouders en niet alleen voor ouders met levensbeschouwelijke bezwaren’. Hier zegt hij dus eigenlijk: schoolonderwijs is voor de kinderen het beste, maar soms zijn ouders het daarin niet met mij (overheid) eens, en als ze dan voor thuisonderwijs kiezen moeten we daar in ieder geval de kwaliteit van controleren.

Aan de andere kant zegt hij: ‘Aan wie komt het recht van onderwijs toe? Ik ga daar een heel eind mee met wat dhr. Van Meenen heeft gezegd, dat het recht op onderwijs een recht is wat kinderen toekomt. Als je kijkt naar het internationaal recht, staat het recht van onderwijs niet voor niets ook in het IVRK. Dat zijn rechten die kinderen hebben, los van hun ouders. En ik vind dat wij ook als overheid een taak hebben om niet alleen de vrijheid en de soevereiniteit van ouders te bewaken, maar dat wij ook de plicht naar kinderen hebben om ervoor te zorgen dat zij los van hun ouders goed onderwijs krijgen [...] het is niet zo dat het recht van ouders om de keuzes voor hun kinderen te maken altijdvoorgaat’. Het idee om kinderen actief te betrekken bij een keuze voor wel/niet thuisonderwijs vindt hij dan ook 'een sympathieke en interessante gedachte'.

Al met al lijkt het er op dat de staatssecretaris er nog niet uit is. Zoals dhr. Bisschop aangaf: het onderwerp is nog niet (voldoende) gerijpt.

Hier: Verslag Algemeen Overleg 16 maart 2016 vindt u een uitgebreid verslag van dit debat, de standpunten van alle partijen, de reactie van de staatssecretaris en de tweede termijn. De audiofile is helaas te groot om te uploaden, maar voor wie wil kan ik deze toesturen (geef dan even een reactie hieronder).

De leerplichtwet zal naar verwachting in 2017/2018 wijzigen.

By Marieke Hopman - 14 March 2016

Monday, March 15 2016

Drove about 350 km today to do research interviews at a quite different side of the country. But it was all worth it: I spoke to a mother and a child who have went through a lot of trouble trying to combine education with the special needs of the child.

Two really great things happened; first, the child who had told his mother he did not want to speak to me (his autism and medical condition sometimes get the better of conversation), decided to speak to me after all and we had a really great and long conversation about his right to education, a conversation that taught me a lot.

Second, I rent the car to get me to this faraway place from private owners through an online system...And I was late to return it. Instead of holding this against me, I just received a message from them that they will not charge me fully as a contribution to my research project...so cool!

Two great things that almost make me forget the feeling of sadness I so often have trouble getting rid of, after a day of listening to stories about unjustice, frustrations, clashes of ideas about "the best interest of the child", and the poor children who almost never get the better of this. You would not believe the children's rights violations occuring in this wealthy, western democratic very civilized country called "the Netherlands" (as, I suppose, in any country if you start doing research..).

By Marieke Hopman - 1 March 2016

Today I am researching the court cases over the past 15-20 years with regard to the child's right to education in the Netherlands. Most cases are very interesting and pose hard questions about who decides over children's education; the local government, the school, the parents, the state, children?

During this research I came across this highly interesting and heartbreaking case. It is a case of a young boy whose parents are deeply religious "Seventh Day Adventists". The boy has walked away from home several times, due to different conflicts with his parents. A most important point here is the fact that the boy is homeschooled by his parents, but he argues that the quality of this education is insufficient (he is only schooled 1,5h per day - which is normal in homeschooling).

When The boy walked away for the third time, he spent 11 days in a self-built improvised tent in a park until the police brought him to youth services. He lives in a young people's home now. At the time of the court case, the boy had been accepted at the local gymnasium (highest level of high school education in the Netherlands).

The great thing about this case is that, in contradiction to many other cases on the right to education, here the boy himself has been heard. We could even say that the position of the child was the central issue to the case. Personally, my heart broke when I read the boys' statement, where he stated that he wanted to go to a regular school, and in addition, that he disliked that his parents refused to hand over his personal stuff such as clothes, bank card and schoolbooks, and also that he 'feels really bad about that his parents have let his pets die'.

By Marieke Hopman - 26 February 2016

Momenteel ben ik bezig met het uitwerken van wat interviews die ik de afgelopen tijd gedaan heb. Hieronder een kort fragment uit een zeer leuk filosofisch gesprek over recht op educatie met D., een jongen van 11 jaar oud. D. vindt het stom dat je naar school moet, dat het verplicht is. We hadden hier een gesprek over:

MH: En wat betekent dan recht op onderwijs? Als ik zeg: kinderen hebben recht op onderwijs.

Resp: Dat ze onderwijs mogen krijgen.

MH: En heb jij dat?

Resp: Nou ik moet het, dus eigenlijk vind ik dat stom.

MH: Leg eens uit?

Resp: ik vind het stom dat ik dingen moet, want, ja de tafel dekken ik snap dat dat handig is. Dus als ze dat vragen dan doe ik het, maar als ze zeggen dat ik het moet, dan zeg ik: je bent niet de baas, ik ben geen slaafje. [...] Eigenlijk, ik krijg recht op onderwijs dus ik mag het, en als ik dan zeg nee ik wil het niet dan komen ze naar me toe en ze zeggen dat het moet. En dat is eigenlijk het stomme aan de regering en aan Mark Rutte en aan zo.

MH: Oké. Maar stel dat we dat niet zouden doen, en jij zegt ik wil niet meer naar school, ik ga niet meer. Als we dan zeggen oké blijf maar thuis...

Resp: Dan leren we niks, nou en? Het is toch ons leven? Het is niet hun probleem, ze bemoeien zich vooral met andermans problemen.

MH: Ja maar waarom ze dat doen, ze zeggen jij bent nog heel jong dus jij kunt nog niet goed begrijpen wat nodig is [...] Bijv leren taal en rekenen. [...] Stel nou dat jij altijd thuis blijft en nooit naar school gaat. Hoe leer je dan taal en rekenen? Of heb je dat niet nodig?

Resp: Ik vind taal heel stom. Want waarom moet je eigenlijk per se zonder spelfouten schrijven?

MH: Dat hoeft misschien niet, maar taal is natuurlijk ook wel, stel dat je nooit leert lezen. Lijkt me wel heel lastig in je leven.

Resp: Als mijn moeder of vader, 1 van de 2 of alletwee kunnen lezen, dan vraag ik aan hun of ze het me willen leren.

[...]

MH: Dan ga je dus wel leren, maar dan thuis in plaats van op school?

Resp: Ja.

MH: Dus recht op onderwijs is dan meer dat je mag leren.

Resp: Maar eigenlijk zeggen ze dan, als ik niet ga, dan zeggen ze dat het moet.

MH: Ja.

Resp: En dat vind ik dus stom.

MH: Ja kun je begrijpen dat ze dat doen eigenlijk om jou te beschermen?

Resp: Tegen wat?

MH: Tegen dat je niet opgroeit op een manier..dat je straks mee kunt doen in de maatschappij.

Resp: Wat is daar erg aan? Ik kan toch ook van vruchten leven? Die gewoon groeien, dan zal ik die gewoon plukken.

MH: Ja dat kan, maar..

Resp: Ze zeggen toch ook dat geld verplicht is? Nou geld is helemaal niet nodig als je gewoon en pompoen tegen een aubergine kunt ruilen.

MH: Ja maar de vraag is of je daar gelukkig van gaat worden.

Resp: Van geld? Geld maakt niet gelukkig.

MH: Nee niet van geld, bijvoorbeeld als je niet kan lezen en schrijven, of van als je bijv nooit op school bent geweest terwijl alle andere mensen om je heen wel naar school gaan [...] als er nou kinderen zijn met ouders, en die ouders willen die kinderen thuishouden. Die zeggen: jij mag niet naar school. Die kinderen wilen misschien heel graag naar school maar die ouders zeggen jij mag niet?

Resp: nou ouders zijn niet de baas , ja ze zijn de baas over kinderen maar de kinderen zijn zelf nog het grootste baas over zichzelf.

MH: Maar een kind wat heel jong is, klein is, als jouw moeder zegt jij mag niet naar school, hoe kom je dan op school? Dat is waar de regering ook tegen probeert te beschermen natuurlijk.

Resp: Nou, als ik nou in een familie zat die hartstikke stom was, net zoals Mathilda, hele stomme familie en ik had geen krachten, zou ik weglopen, zou ik aan mensen vragen of ze wisten of ik het kon eten of niet als ik bv met pepermunt aan kwam of met basilicum ofzo..en dan ga ik gewoon zo rondtrekken en het enige wat ik meeneem is een paar kleren en een beetje voedsel. Dat ik nog kan overleven.

MH: En waar ga je slapen?

[...]

MH: het punt is meer dat ik denk: nou maar je hebt toch ook een beetje bescherming nodig? Of niet? Is toch ook goed dat jij een beetje beschermd wordt?

Resp: als ik later zelf mocht bepalen wat ik zou doen, zou ik denk ik met vriendinnen, ik moet later op kamers, dan zou ik gewoon met vriendinnen, we worden dan gewoon huisgenoten ik zou daar dan gewoon super leuk mee samenwonen. [...] als we met z’n vieren op stap zouden gaan, dan zou ik het denk ik gewoon, ja fijn vinden.

MH: Ja? En dan hoef je niet echt te leren lezen, schrijven en rekenen?

Resp: Nee. Maar kijk, wat makkelijk is, als de ene nou gewoon een taalvak leert, en de andere het rekenvak en de andere weer geschiedenis en de andere weer dansen, dan hoeven we maar één ding te leren op school, dan leren we dat uitgebreider en dan kunnen we daarna samen tijd doorbrengen terwijl we leren want dan kunnen we van elkaar leren.

MH: O ja. Maar dan is het weer hetzelfde als school want daar leer je toch ook van elkaar?

Resp: Nou vooral van de juffen en meesters.

MH: Ja maar die hebben het dus eerder geleerd van iemand anders.

Resp: Maar wie heeft dan de taal uitgevonden?

MH: Ja, dat ontstaat een beetje hè. Er komen ook steeds nieuwe woorden bij.

Resp: En wie is er ooit begonnen met leraar zijn? Wie is de allereerste leraar?

MH: Wat denk jij? [...] ik denk dat je al heel snel leraar bent als je een beetje ouder bent..bijv, als je een kind en een volwassene hebt, en zeker als we, zelfs bij dieren moet toch ook de moeder leren aan het kind hoe je bijv moet jagen.

Resp: of vlooien van elkaar afhalen.

MH: bijvorbeeld. Alles moet je eigenlijk leren, als je nieuw komt op de wereld dan kun je nog helemaal niks. Toch? Kijk maar naar een baby.

Resp: Een baby kan ademhalen,

MH: Ja dat hoeft je niet te leren

Resp: knipperen met z’n ogen, kijken, ruiken, zien

MH: Dat is waar. Maar als je een baby alleen in het bos zou laten...denk niet dat ie dat redt

Resp: met wilde dieren, dat overleeft ‘ie niet.

MH: Maar hoe gaat ‘ie eten ook? Baby’s kunnen in het begin nog niet kruipen hè.

Resp: ja...

Ik weet nog steeds niet goed wat ik moet met het "je kunt toch van vruchten leven"-argument. Ik heb dit vaker van kinderen gehoord, maar het lijkt me toch niet helemaal realistisch. Hoe moeten we dit duiden? Wat moeten we hiermee? Mocht iemand een idee hebben, kun je hieronder reageren (graag!).

By Marieke Hopman - 9 February 2016

Dear all,

By now I have interviewed about 20 people on the right to education in the Netherlands, of whom about 50% children. Some of these people had positive experiences with education, some negative. What seems to be a big factor in how children experience their education is the amount of enforcement involved.

How do you remember your education? Was/is it something you do because you MUST or something you do because you WANT TO?

Today I met a 10 year old boy who had even more trouble than most children with the obligatory character of education. He simply felt greatly unhappy with teachers telling him what to do ("today you finish paragraph 5.1 of maths and you read 10 pages", etc). Philosopher Michel Foucault compared a school to a military institution. According to Foucault, schools are focused on teaching discipline, like a military academy. Students are taught discipline like soldiers. You can see this by how even the physical side is forced; you have to sit/stand/walk/stand in line when the teacher tells you to, the timetable is strict.

Any student should who has a problem with authority will not make it to the diploma.

However, the boy I met today now does not study much at all. He is at home most of the time, and his parents are trying to give him space for him to find out what he wants and to start studying it. They believe that with time, something will interest him and he will find the motivation to study, because it is interesting to him. After all, you can learn how to read and write and calculate not only from studybooks. Imagine for example that you find a great interest in stars, you will want to study stars by reading about them, maybe take notes, explain them to others, calculate their positions.

The idea sounds great and wouldn't it be great if school was just much more FUN? Or can it not be all fun? Does the right to education involve a duty to study?

By Marieke Hopman - 14 December 2015

Bij deze de eerste video over het veldonderzoek in Nederland: hoe werkt dit precies, wat voor gesprekken ga ik voeren, op welke manier en met wie?