Study along on children's rights

On this page you find some study material on the subject of children’s rights. The material includes study texts, an introduction to the topic and suggested discussion points. The material currently on this page is the content of a series of discussion meetings held with employees of Defence for Children the Netherlands between November 2015 – July 2016. Please note that some of this content is available only in Dutch. In the future we hope to share more children’s rights study material.

By Marieke Hopman - 12 July 2016

Introduction

In everyday legal work we generally take the state law and international law as the ultimate sources of law that guide our work on a daily basis. This position takes the conventional concept of “law” to mean “state law” or “international law”. However, this idea has been criticized by many great thinkers such as for example Eugen Ehrlich, Max Weber, Boaventura de Sousa Santos and Leopold Pospisil. They argue for an understanding of law that recognizes laws other than those rules issued by the state. Some even argue that the tendency to identify law with state law adheres to ‘the ideology of state centralism’,[1] and call for an ‘uncoupling of law from the state’.[2]

These researchers adhere to what has been called “legal pluralism”; the idea that it is possible to say that multiple legal orders coexist in the same social field, [3] that the state is not the only legal order, that there are other laws except state law.

If they are right, lawyers might have to look further than state or international law to understand the legal situation many people (and, notably, children) find themselves in. Ehrlich in this respect criticized legal practicioners, saying that ‘the jurist does not mean by law that which lives and is operative in human society as law, but, apart from a few branches of public law, exclusively that which is of importance as law in the judicial administration of justice’.[4] Instead, he proposed that the jurist has ‘to look not only at the law, but at the whole of legal life, whether it accords with the law, whether it runs contrary to the law or whether it fills the gaps of the law’.[5] In this way, legislators can legislate more effectively, because they will be better aware of the consequences of rules they install,[6] scientific research on law will become much more relevant[7] and jurists can use real life in the courtroom.[8]

Pospisil took Ehrlich’s idea and applied it to his own field research, firstly demonstrating how law among Kapauku Papuans, Nunamiut Eskimo and Tirolean peasants,

‘the decisions of the leaders of the various subgroups bore all the necessary criteria of law (in the same way that modern state law does): the decisions were made by leaders who were regarded as jural authorities by their followers […] these decisions were meant to be applied to all “identical” (similar) cases decided in the future […] they were provided with physical or psychological sanctions […] and they settled disputes between parties represented by living people’.[9]

He therefore claims categorially that ‘every functioning subgroup of a society has its own legal system which is necessarily different in some respects from those of the other subgroups’.[10] An individual is simultaneously a member of several subgroups, such as the household, the lineage, etc, and consequently the same individual may be subject to different and sometimes contradictory laws of different legal systems.[11]

However, this is not exclusively the case when it comes to more primitive or exceptional societies. Pospisil sees the same kind of legal systems operating in Western society; in the USA for example, ‘there exists, besides the federal or national legal system that is applied to the whole society (nation), the legal systems of its component states’.[12] But he goes even further and controversially argues that ‘even a small grouping such as the American family has a legal system administered by the husband, or wife, or both, as the case may be. Even there, in individual cases, the decisions and rules enforced by the family authorities may be contrary to the law of the state and might be deemed illegal’.[13] Other examples of legal subsystems are the criminal gang, the province, the village, the clan, gilds.[14]

[1] John Griffiths, 'What is legal pluralism?' (1986) 18 The journal of legal pluralism and unofficial law 1-55 3.

[2] Boaventura de Sousa Santos, Toward a New Legal Common Sense: law, globalization, and emancipation (second edn, Cambridge University Press 2002) 68, 85.

[3] Sally Engle Merry, 'Legal pluralism' (1988) 22 Law and society review 869-96.

[4] Eugen Ehrlich, Fundamental Principles of the Sociology of Law (Harvard Studies in Jurisprudence, Arno Press 1975): 9-10.

[5] Eugen Ehrlich, Manfred Rehbinder, Gesetz und Lebendes Recht: vermischte kleinere Schriften (Duncker & Humblot (1986): 232, 234.

[6] Ibid: 238-39.

[7] Ehrlich, 1975: 493, 1986: 237.

[8] Ehrlich, 1986: 237.

[9] Pospisil L, 'Legal levels and multiplicity of legal systems in human societies' (1967) 11 Journal of Conflict Resolution: 9.

[10] Ibid: 9.

[11] Ibid: 9. The term “legal system” is used interchangeably with “legal level”.

[12] Ibid: 13.

[13] Ibid: 13-15.

[14] Ibid: 13.

By Marieke Hopman - 21 March 2016

Introductie

Carrie v.d. Kroon is in 2013 in Panama en Costa Rica geweest voor veldonderzoek onder de Ngäbe bevolking, een inheemse bevolkingsgroep van Panama. Haar onderzoek richt zich op het deel van de bevolking dat jaarlijks naar Costa Rica reist om daar op de plantages koffie te plukken.

In haar artikel focust v.d. Kroon op de ervaringen van de 52 kinderen waarmee zij sprak, van wie zij door middel van rechtsantropologische methodologie en interpretatie wil weten hoe het stond met hun rechtsbewustzijn (p. 218). De antwoorden die de kinderen geven legt zij naast informatie van volwassenen, opgedaan vanuit gesprekken met lokale professionals en literatuurstudie (p. 219).

Wat opvalt is dat er een grote discrepantie is tussen het internationale (kinder)rechtenkader, en de dagelijkse ervaringen van kinderen, inclusief de betekenis die zij hieraan geven. Aan de ene kant wordt in de literatuur een zeer negatief beeld geschetst van de situatie van deze mensen: ‘[d]e arbeidsmigranten van de Ngäbe-Buglé […] bevinden zich in de moeilijkste positie, daar zij “verreweg de meest uitgesloten en armste migranten zijn”’ (p.221). De kinderen zijn daarbij nog extra kwetsbaar. V.d. Kroon conludeert dan ook dat het hier dus gaat ‘om de meest gemarginaliseerde van de gemarginaliseerde groepen, die het minst zichtbaar zijn en het minst gehoord worden’ (p. 221). Aan de andere kant concludeert zij op basis van de gesprekken met kinderen: ‘de Ngäbe-kinderen zijn zonder uitzondering enthousiast wanneer zij denken aan Costa Rica’ (p. 219). Zij vinden het een mooi land, vinden het werk, de natuur en het huis waar ze wonen leuk (p. 219, 221-24).

Wat zegt dit over het rechtsbewustzijn van kinderen? Volgens v.d. Kroon zijn de kinderen zich ‘wel degelijk bewust van hoe dingen ‘horen’, wat wel en niet mag […] Zij spreken in termen van goed en kwaad […] regels en verantwoordelijkheden, zonder dit aan formeele rechten te koppelen’. Op basis van de bovengenoemde discrepantie geeft zij aan dat ‘op basis van de (negatieve) beelden van volwassenen omtrent kinderarbeid en abstracte, universeel geldende mensenrechtennormen die kinderen moeten 'beschermen', maatregelen genomen kunnen worden die volgens kinderen en adolescenten zelf niet noodzakelijk noch gewild zijn’ (p. 227).

In de afsluiting van het artikel lijkt ze echter toch een knieval te doen richting dit volwassenen mensenrechtenkader, wanneer zij schrijft dat het gat tussen de universele mensenrechtennormen en de realiteit in Centraal-Amerika kan worden gedicht ‘door het opstellen van uitvoeringsplannen, het toekennen van budget en dit specifiek te maken voor de doelgroep [etc.]’ (p. 231).

Discussiepunten

- Hoe kunnen we toegang krijgen tot het rechtsbewustzijn, en met name het “morele kompas” (p. 227) van kinderen? Is dat belangrijk?

- Welke rol speelt dit rechtsbewustzijn van kinderen in het vaststellen van (mensenrechten)beleid?

- Moeten we op basis van internationale kinderrechtenverdragen maatregelen doorvoeren, ook als dit tegen de wil van een bevolkingsgroep, inclusief de kinderen, ingaat?

- Hoe komen we dit tegen in ons eigen, dagelijkse werk?

- Gaat deze vorm van kinderarbeid in Costa Rica in tegen het IVRK? Zouden we bv kunnen zeggen tegen deze kinderen “jullie werk is een belangrijk deel van jullie educatie, jullie ontwikkeling naar volwassenheid”?

By Marieke Hopman - 16 February 2016

Introduction

Professor Ronen analysis the child’s right to identity (CRC art. 8). Central to his analysis is the possible tension between individual identity as resulting from a liberal individualistic ethos (p. 151) and an individual identity as resulting from an ethos of interdependence (p. 151). This is a possible tension which we encounter in the CRC art. 8; on the one hand, the child’s identity is assumed to be composed of individual aspects (such as a name), on the other hand emphasis is laid on interdependent aspects (such as family relations).

Another possible tension identified by Ronen in relation to art. 8 is the tension between the child’s need ‘to become’ and the child’s need ‘to be’ (p. 150). Ronen argues that ‘a children’s rights regime should ideally be responsive’ to both (p. 150). This means that that the child, as a child, is more than the property of the state or parents, and therefore we have to recognize the child ‘as an individual, whose authentic identity is worthy of respect’(p. 151-52). In addition, we have to recognize the cultural and specifically familial context that is meaningful to the child (p. 152-53), even if these contexts ‘may not conform to socially accepted values’, because it will ‘contribute to the moulding of an authentic self’ (p. 153).

Finally, Prof. Ronen argues for taking up the child’s perspective in protecting the child’s identity; ‘the definition of the right to identity should enable the decisionmaker to understand that the little the child sees as their identity, should, in principle, be protected’ (p. 155-56).

Possible points of discussion

- How do we balance the child’s need ‘to be’ and it’s need ‘to become’ in relation to identity?

- Is Ronen right when he argues that ‘legal recognition of an individualized identity does not imply endorsement of a traditional liberal individualist ethos’, because ‘it is founded on an alternative ethos of interdependence’ (p. 151)?

- How do we in our work regard/disregard the child’s ties to ‘communities, families and adults meaningful to the child’, because we see them as ‘deviant, morally impaired or simply less than full human’ (p. 152)? Should we, als children’s lawyers, ‘positively protect those elements that contribute to the moulding of an authentic self’ (p. 153) and ‘reject the notion of a ‘normal’ identity’ (p. 156)?

- (How) should we encourage the child’s participation in defining who they are (p. 153)?

- Do we have to beware not to act out our ‘fantasies of saving children’, as they ‘may turn out to be painful for the children involved if they are not heard and understood as human being possessing a unique identity’ (p. 155)?

By Marieke Hopman - 5 January 2016

Introduction

In her chapter, van Walsum presents a historical analysis of Dutch family law and migration law, starting with the the post-war period in 1945 and the policies related to decolonization. One of her questions is whether we draw parallels between racist and genderdized policies of the past to current practices.

Another important observation the author posits links the exclusion/inclusion proces to individual norms and values. According to van Walsum, after the traditional emphasis on the nuclear family with the “male breadwinner citizen” as head of the family (p. 60), in more modern times we put a normative emphasis on the individual, self-sufficient citizen (p. 62). In fact, we posit the self-sufficiency of the individual as a condition for granting citizenship (p. 66).

So, with the decline of the emphasis on the nuclear family and changing family constructions, what is the position of the child in all this? According to the author, current Dutch migration policy is in the first place focussed on protecting the modern national (wester, liberal) norms of individual responsibility, equality and freedom (and capitalism). This “new citizenship” (p. 68) constitutes the main reason for acceptance or exclusion in the Netherlands. This can explain, for example, why children who grow up in a foreign country are excluded from Dutch citizenship even if the parents are Dutch citizens through naturalization (p. 66).

Discussion

- What is the status of the child in the migration process, in relation to the Dutch state and the family? Are children seen as family-members or as private individuals? (van Walsem p 69: ‘The family is being broken down into its component parts and family members are being treated as separate, equal and independent’).

- How does the position of the child relate to the normative ideal of the self-sufficient citizen, who takes up individual responsibility etc?

-> I found this point particularly interesting in relation to our last discussion on the text of O’Connell Davidsson. As van Walsum writes, through social policies, individual self-sufficiency is enforced and there is an emphasis on individual responsibility (p. 62). However, it is often argued that children cannot take on this responsibility and often they do not even have the right to work, making them financially dependent on their parents (especially because there are no welfare benefits for <18). While at the same time older children are apparently assumed to be (almost) fully ethically formed, as they are perceived to be an integration risk due to their foreign upbringing. So here both the adolescent who runs away from home and tries to make a living (eg through prostitution, one of the few options available in that case) and the foreign child whose parents are Dutch citizens seem to find themselves in a similar legal incoherent limbo?

- And how does this relate to the position of children who are raised and educated in the Netherlands, thereby forming an integration risk to other countries, but who do not get citizen status? And what about their relations to their families?

- What is the link between immigration law, family law and integration policies (p 67)?

- What is the role of the normative framework of the nation in determining the exclusion/inclusion policy? Does it affect current Dutch nationals too? (should it?) (p.68)

By Marieke Hopman - 16 December 2015

Text: O’Connell Davidson, J. (2005) Children in the Global Sex Trade. Pages 25-36, 39-42.

Introduction

Julia O’Connell Davidson is a professor known for her work on human trafficking, human slavery, sexual abuse and children’s rights. The research for her 2005 book on children in the global sex trade was in fact paid for in great part by ECPAT International. However, at the same time she expresses herself as very critical of all NGO campaigns that are depicting commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) as “innocence destroyed” (p.2). In the book she aims to ‘deconstruct the presumed boundary between adults and children in the sex trade’ (p. 3).

Following Jenks, she argues that the extreme emotional reactions following child sexual abuse have ‘intense political significance’, because ‘they work to hierarchize our political order (p. 7). The adult disgust over these practices affirmes the inferiority of children (p. 7), we need children to be unlike us, because ‘children are the ‘gift’ that couples can give to each other in order to secure their own relationship as well as to establish social links with each other’s kin’ (p. 18-19). Finally, the whole of emotions, reactions and significance leads to “big business” for anyone willing to work on child (sexual) abuse (p. 8).

We will zoom in on O’Connell Davidson’s analysis of the understanding of childhood as it has been present in history and different cultures, which she couples to the understanding of social categories “women”, “prostitutes”, “slaves”, and presenting a sharp analysis of ECPAT International discourse..

Possible points of discussion

- How do we and our partners use the image of the ‘child sexual slave’ as ‘a particularly potent symbol of undeserved suffering’ for fund-raising and lobbying (p. 25-26, 31-33, 41-42)? What are the effects of this policy? Do we choose this consciously?

- How does the discourse have effect on us, on our thinking, acting, work, etc?

- How is prostitution understood/treated in different times (p. 27-28)?

- Is there a crucial difference between adult prostitution and child prostitution, and if so, what is it? (p. 29-30, 34-36, 41).

- Is the despising of child prostitution relative to historic times (“after the enlightenment”) and cultural values (focus on Asia, Western values?) (p. 31)?

By Marieke Hopman - 8 December 2015

Last study group we focused on the how we can evaluate the role of child participation. When children get the possibility to participate, in research or in other contexts (school, NGO work, family), ethical questions arise such as who can consent to participate (child or adult or both)? How can adults listen to children? Can adults be open to children's agenda's? Who analyzes, presents and owns the results?

Thomas & O'Kane wrote The Ethics of Participatory Research with Children in 1998, which discusses these questions in relation to their research on decision making in the world of children who were looked after by local authorities. The authors argue that underlying the ethical issues, is the perspective one takes on children and childhood (p. 338).

Here you can find the document that introduces the study hour on ethics and child participation.

By Marieke Hopman - 17 November 2015

In childhood research and children's rights research, as with people who work directly with children in different capacities, "child participation" is a hot topic. The idea is that we should not (always) decide over children, as adults, but we should decide over children's lives with children. Children have the right to participate according to several UNCRC articles, such as art. 12.

One of the questions relating to this development is the question how we can evaluate child participation. How can we tell when a child program or research is sufficiently participative?

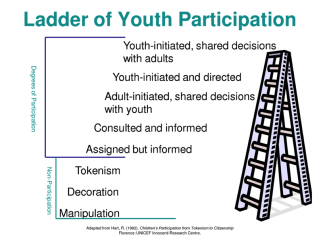

Roger A. Hart developed a "participation ladder" in a 1992 UNICEF report, which is still often used to measure and evaluate the level of child participation to certain projects.

Then, in 2008, he wrote another paper titled "Stepping back from 'The Ladder': Reflections on a Model of Participatory Work with Children". In this paper, he more or less distances himself from the way the ladder of participation is being used by many children's rights organizations, arguing that his 1992 article 'was simply meant to stimulate a dialogue on a theme that needed to be addressed critically. But many people have chosen to use the ladder as a comprehensive tool for measuring their work with children rather than as a jumping-off point for their own reflections' (p. 19). He points to the dangers of glorifying participation without critical reflection, as for example ‘a child may not want at all times to be the one who initiates a project’ (p. 24).

Questions to be discussed during tomorrow's study hour with Defence for Children colleagues include:

1. Can we have a ladder-model of child participation? Is more participation better than less?

2. Is the idea of child participation culturally determined (as Hart claims on p. 26-28)?

3. How can we evaluate child participation?

Here you can find the document that introduces tomorrow's study hour.

By Marieke Hopman - 4 November 2015

As of today I am organizing a two-weekly study hour with children’s rights specialists, discussing recent academic works on children’s rights. On this blog I will share the texts and preparation of the study hour, so that anyone who is willing can study along.

Today we had our first meeting and it was most inspiring! We discussed Jenks’ Childhood, chapter 4. Jenks wonders why in recent decades child abuse seems to have greatly risen. He argues that child abuse is a phenomenon of all times, and that what has changed is our attitude towards childhood.

For Defence for Children jurists, one of the interesting questions was how our view of childhood influences our work. Do we work for the protection or empowerment of children? Are children’s rights controlling/protecting or empowering? Is Jenks right when he argues that in the child, we preserve the lost meta-narrative of society (a story of love and innocence)?

Here you can find the text that we read and my introduction, including discussion questions (last document in Dutch). So anyone who’s interested can join our studies at home :-)!