Moroccan controlled Western Sahara: freedom of expression

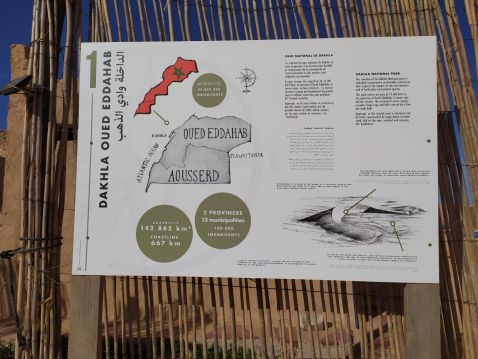

Since 1976, a large part of the Western Sahara has been under Moroccan control, who claim it as part of their national territory. This claim has been disputed under international law (see also this blog). Currently the territory is populated mostly by Moroccan and (indigenous) Sahrawi people. As part of our study on the development rights of children living in unrecognized states, we visited this area and studied the rights of children living here. Because we deemed this the most prominent children’s rights issue in the area, this case study focuses on the child’s right to freedom of expression. You can find the report presenting the results of this case study here. Below you find all the blogs and vlogs related to this case study.

16 November 2022 - By Marieke Hopman

I am very happy to hereby share that the International Journal of Human Rights has recently published an article that present some of the findings of the case study on the child’s right to freedom of expression in Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara (MCWS). You can find the article here.

Who limits free expression for children?

The article itself is a controversial piece, since it present findings that are in some respects different from what other researchers and NGOs have published on this topic. Our findings show that, contrary to the stories (“narratives”) presented by most research and activism around human rights in the Western Sahara, the child's right to freedom of expression is limited by different groups. It is limited not only by the Moroccan state, but also by other social orders such as the community, the family and the school. Children in MCWS are not allowed to speak freely about religion, sexuality, and the Western Sahara issue. This is true for both Moroccan and Sahrawi children living in MCWS.

Dominant narratives

Children in MCWS learn from an early age that they should not discuss certain topics, to avoid violent consequences by state authorities, teachers, community-, and/or family members. You might say that a policeman is installed in the child’s mind, making the child ask ‘can I say this?’, or even ‘can I think this?’. In particular regarding the Western Sahara issue, two dominant stories (narratives) have been established, which tell children what they are and are not allowed to say or even think, about the subject. These two dominant narratives are the narrative of the Moroccan nationalists on the one hand, and of the Sahrawi activists on the other. According to the Moroccan nationalists, the Western Sahara is Moroccan territory. According to the Sahrawi activists, Morocco is illegally occupying the Western Sahara, a territory that belongs to the indigenous Sahrawi people. Sahrawi activists claim that Morocco is actively trying to eradicate the Sahrawi identity, and that Moroccan authorities are prosecuting every Sahrawi who speaks up. According to Moroccan nationalists, all people in MCWS have completely freedom of expression. The Sahrawi people can do anything they like, except engaging in violent protest.

All children growing up in MCWS, both Moroccan and Sahrawi children, have to relate to these narratives. The Moroccan narrative is taught in schools, and children are not allowed to question it. The Sahrawi narrative is taught in the homes of Sahrawi activist families, and children may not be allowed to question this either.

We also found that research and human rights activism are (unintentionally) part of the problem, because they have a tendency to present one sided stories that are in line with one of the dominant narratives.

A third narrative

However, the research also presents a hopeful message: in MCWS we found a third narrative. This third narrative tells us that while historically Morocco may or may not have had a right to take control over the Western Sahara, the fact is that Morocco rules over MCWS and has done so for a long time. Moroccan and Sahrawi children mix in everyday life on a daily basis. They go to school together, they may be friends or neighbors. Although there is no complete freedom of expression in MCWS, there is space for Sahrawi culture in Moroccan society.

This story is not heard often, because it is the story of everyday people, who do not necessarily speak up. They are not activists and they do not want to risk being prosecuted for telling their story. But it does exist. And I am hopeful that this third narrative can increasingly create space for a conversation where children are free to discuss their questions, thoughts and ideas.

12 April 2022 - By Marieke Hopman & Emilia Klebanowski

We are happy to share that we have now submitted the UPR shadow report on the right to freedom of expression with the UN Human Rights Council. You can read the report here.

The report was submitted in collaboration with: Adala UK , Global Human Rights Defence, terre des hommes Deutschland, terre des hommes schweiz and Western Sahara Campaign.

As you will see, in this report we list the ways in which the Kingdom of Morocco is protecting this right for its people, and in what ways this protection can be improved. We discuss both the legal protection of this right (are Moroccan laws written well so that this right is properly protected?), as well as the protection of this right in practice (do Moroccan authorities such as the police and the courts protect this right in practice?). In some cases there is adequate protection, but as you will read in the report, in many cases there is room for improvement. In some cases both the Moroccan law and the practice by authorities are actually violating international human rights law.

At the end of the report you will find a list of recommendations that we have drafted based on our research. These are recommendations to the Moroccan government, and we hope that other States who are part of the UN Human Rights Council will encourage Morocco to take up these recommendations.

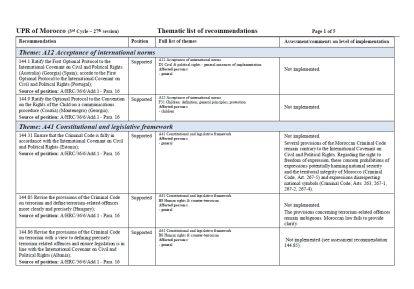

The report comes with two attachments: first, a list of suggested advance questions: this is a list of questions that other States might ask Morocco. Asking the state under review questions about the human rights situation is part of the UPR process, as explained in this blog. Second, an OCHCR Matrix with a list of recommendations made during the UPR session in 2017: this is an overview of all the recommendations that states made during the last UPR cycle. The overview includes these recommendations, the position of Morocco (whether they supported the recommendation or not), and lastly, whether they indeed implemented these recommendations. As you can see in the overview, unfortunately, none of the recommendations related to the right to freedom of expression were implemented.

29 March 2022 - By Marieke Hopman

It is always difficult to find reliable information on possible human rights violations in general, and in particular in areas under the control of authoritarian regimes. These areas often lack an open culture, where people feel free to speak their minds and share their thoughts with a researcher. Instead, maintaining control over information is an important task of the authoritarian regime. You may even go to jail for asking certain questions, or for giving certain answers.

As researchers, we are therefore faced with a dilemma when we want to study the rights of children who are living in such an area (see also this blog). In our case, we wanted to study the rights of children who live in the part of the Western Sahara that is under Moroccan control. To do so in the most objective way, we chose to use the method of “covert qualitative research” (aka undercover research). This means that you do research, you observe the subject of your research and you speak to people who can inform you about the topic, without telling anyone that you are a researcher. This is a very controversial method, because it means actively lying to people. Therefore, the method is not often used by researchers. When we started this case study, we couldn’t actually find any information on how to do this exactly. In this blog I will therefore discuss two matters:

- How to apply this method

- Whether it is ethically acceptable to use this method

For the academic journal article on which this blog is based, please click here.

How to do covert qualitative research

The first thing about covert qualitative research is that you don’t tell anyone (except your colleagues) what the true purpose is of your presence in a certain field. In our case, we travelled to Morocco and then further south to what Morocco considers its “southern provinces” (Western Sahara under Moroccan control). We travelled there as tourists and always acted as tourists.

Sampling

Choosing who to talk to (sampling) has to be aligned with the role chosen by the researcher. As tourists, it made sense for us to travel around in the area, to observe, and to speak to people in the streets on occasion. It also made sense for us to have conversations with many people in the tourism industry, such as travel guides, waiters and hotel receptionists. A problem that we encountered in our case, was that through this sampling method we included mostly men. We then tried to actively search for female research subjects, by trying to find public spaces where we might meet women. We registered for a manicure, cut our hair in a female-only hair salon, and went shopping. Unfortunately, this was only mildly successful since many women didn’t speak a language that we spoke.

Research conversations

If you don’t tell anyone you’re a researcher, it is very difficult to have conversations that provide you with useful information, but it is not impossible. This is what we learned:

- It is important to limit the number of questions you ask.

While it is normal as a tourist to be curious and interested, asking questions all the time can be suspicious or simply annoying, both resulting in you not getting too much information. We limited our questions to three categories: 1) fun questions; 2) questions on something the respondent was eager to talk about; and 3) questions relevant to the research topic (for us: children’s rights).

- Weave your questions into more casual conversation

One way to do this is to take a remark made by the respondent themself and turn this into the direction of the research topic. For example, in our experience, someone would ask ‘how do you like [name city]?’, to which we would answer with something we noticed, for example ‘I really like how everyone seems to love children! Is that right?’. A second way is to express something about your own life or experience and ask the respondent what this is like in their country. A third approach is to present an experience you have had in the country and to ask what it meant.

- When balancing between research questions and casual conversation: better to err on the side of caution

We found that if we pushed the conversation too much into the direction of the research, we ran the risk of making people feel uncomfortable or the situation getting tense. If you have to choose, better to leave the conversation lighthearted.

Data protection

In a situation where people did not choose to participate in a study, but their answers are still used as research data, the least you can do as a researcher is do your best to make sure that this information is stored safely and anonymously. For this purpose, we stored all our data in a secure cloud that could only be accessed through a particular type of VPN connection. Read more about how we did this in this paper.

Limitations of the data collected

The data you collect will most likely be very valuable, but limited. While the data is very objective (no one is trying to manipulate your research outcome since they don’t know that you are a researcher), it is also very limited. For example, you may not have access to locations you might like to study, or to certain types of respondents who are less present in the public space, and you are often not able to discuss your research subject directly. In our case, we also did online interviews with several respondents with whom we got in touch through social media after the field research.

Ethical dilemmas

As mentioned above, this method comes with a lot of ethical concerns. First and foremost, is it fair not to tell people that you are actually a researcher, and to use things that they say in confidence as research data, without telling them at all? In general: of course it is not. But I believe there are exceptions. In this case, I think this method was the best one to use because:

- The aim of the research was to contribute to the protection of children’s rights.

- We were very careful to make sure that all respondents would stay anonymous.

- There was no other, more transparent way to obtain the necessary data.

Under these conditions, I believe that this type of research method is warranted, and actually it is even a good thing if in this case people go and do this kind of research. The alternative is that no research is done at all on children’s rights in authoritarian zones. Before our study, there literally was no academic study on the children’s rights situation in this part of Western Sahara. And this is mostly due to the fact that Morocco actively prohibits this type of research.

Conclusion

To conclude, I believe that covert research methods can ethically speaking be used to study the children’s rights situation of children who live in authoritarian zones. Although there are obvious disadvantages to this method, if the alternative is to have no information at all about a children’s rights situation in a certain area, I think using this method and doing research is preferred over doing nothing. From an ethical perspective, in such cases, it may even be ethically required to do this kind of research, to make sure that certain violations of children’s rights do not go unnoticed. Therefore, if there are authoritarian zones where research on children’s rights violations is not possible other than through covert research, hopefully there will be researchers willing to travel there and studying the situation as undercover researchers.

To learn about the outcome of this case study on the child’s right to freedom of expression in Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara, see these blogs and vlogs, and this report.

2 December 2021 - By Emilia Klebanowski

When studying the right to freedom of expression in Western Sahara we found a lot of information which we would like to share with the United Nations Human Rights Council within their Universal Periodic Review (UPR) process. Morocco is up for review in May 2022. Below I will firstly, explain what the UPR process is, secondly, elaborate on why Moroccan law does not protect the right to freedom of expression completely and thirdly, talk about the practice by Moroccan authorities.

What is the UPR?

Every five years each member of the United Nations (UN) has to report to the UN Human Rights Council, which is the UN body responsible for the promotion and protection of human rights. States have to report on how they are doing in terms of human rights. Have they protected the rights of their people well in the past five years? What went well, what can be done better, and how are they planning to improve? This process is called the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) process. To check if the information provided by these states is complete and correct, the Human Rights Council asks civil society organizations to produce “shadow reports”, which are reports providing information on the human rights situation on the ground. So that is exactly what we did, together with our partner organizations.

Since this report is about the State (in this case Morocco), we can only report what Morocco does or does not do to protect the right to freedom of expression. So, what according to our report are the main issues?

Why Moroccan law does not protect the right to freedom of expression completely

Under Moroccan law, everyone has a right to freely express themselves. Morocco has also consented to comply with major human rights treaties which safeguard the right to freedom of expression. This means that Morocco is under an obligation to protect the right to freedom of expression, and if it does not, it can be held accountable. This may sound great at first, so what exactly is the problem with Moroccan law? During our research we found that there are some parts of Moroccan law that actually restrict the right to freedom of expression. Some of these restrictions are in line with international human rights law, others, however, are illegal. Generally, Moroccan law does not allow:

- Undermining, insulting, or questioning the Moroccan King or royal family

- Expressions undermining Islamic religion

- Expressions potentially harming the national security and the territorial integrity of Morocco

- Expressions disrespecting national symbols, such as the Moroccan flag or hymn

- Expressions including false accusations or information

In this blog post I will focus on one of these restrictions, namely expressions undermining Islamic religion.

A prohibition on expressions that undermine Islamic religion

Why is it problematic that Moroccan law restricts expressions undermining or questioning Islam? Why is it contrary to international human rights law? The Human Rights Committee stated that prohibitions on expressions that disrespect a religion are incompatible with international human rights law. This means that if someone criticizes or questions Islamic religion, this should – in principle - be allowed by the State. However, there is an exception to this. If someone criticizes religion in a way that amounts to hate speech, then this is not allowed. The Cambridge Dictionary defines hate speech as “public speech that expresses hate or encourages violence towards a person or group based on something such as race, religion, sex, or sexual orientation”. The threshold for an expression to be considered “hate speech” is rather high, since limitation of speech must remain an exception. Ordinary expressions criticizing or undermining Islam do not reach that threshold.

Now some might argue that expressions that criticize Islamic religion interfere with someone else’s right to freedom of religion. According to UN experts, this is not the case. Two independent experts appointed by the Human Rights Council, the UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief and the UN Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, xenophobia and related intolerance, said that

“[Criticism] of religions may offend people and hurt their religious feelings, but it does not necessarily or at least directly result in a violation of their rights, including their right to freedom of religion. Freedom of religion primarily confers a right to act in accordance with one’s religion, but it does not bestow a right for believers to have their religion itself protected from all adverse comment.”

In sum, the scope of this prohibition in Moroccan law is too broad, since it prohibits any expression undermining Islamic religion. Looking at international human rights law only those expressions reaching the threshold of hate speech should be prohibited – and certainly not all expressions.

In case you are working with a CSO/NGO that is interested in co-submitting the UPR report on the right to freedom of expression in Morocco and Western Sahara, you can

12 Novemer 2021 - Florentina Pircher & Marieke Hopman, Wesside Stories

Doing research on children’s rights in the Moroccan-controlled area of Western Sahara is generally not allowed by the Moroccan authorities. Nevertheless, we visited this area as part of our study on the rights of children living in the Western Sahara. What was it like to do “undercover research”?

27 October 2021 - Florentina Pircher & Marieke Hopman, Wesside Stories

This introductory vlog provides an overview of our research project on the rights of children living in the Western Sahara, a territory claimed by both Morocco and the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic. Since very little is known about the situation of children in the Western Sahara, the subsequent vlogs will present the findings of this field research.

By Marieke Hopman - 24 August 2021

As you may have read, early June we presented a draft report of our study on the child’s right to freedom of expression in the area “West of the Berm”, or the part of the Western Sahara that is under Moroccan control. We invited everyone who was interested to give us feedback on the content of this report. In addition to the online presentation and sharing the report on social media, we also sent physical copies of the report to a large number of relevant actors in the area (ministries, schools, NGOs). We received a handful of comments from different actors, see also this blog. Based on these comments we made a few (small) changes to the text of the draft report, and we hereby present the final report. Of course, we still welcome any opportunity for discussion, so please

By Marieke Hopman - 17 June 2021

Today I received a phone call from a young person who lives in the area “West of the Berm”, which is the area of the Western Sahara that is under Moroccan control. This person had read our report and wanted to discuss the content. He said “I really like you research, but there are some things that you didn’t include”.

The caller wondered why we didn’t discuss the legal status of the area. Why didn’t we indicate that the territory is illegally occupied? We actually received this question a lot from the Sahrawi community. They wonder: Why don’t we mention that under international law, the authority of Morocco over this part of the Western Sahara is considered an occupation? Some may even be angry that we don’t mention this, because of their strong feelings regarding the injustice of the political situation. Their claim of the illegality of Moroccan authority over the area is mostly based on the advisory opinion on Western Sahara by the International Court of Justice (ICJ). The court found that while at the time of Spanish colonization there were ‘legal ties of allegiance between the Sultan of Morocco and some of the tribes living in the territory of Western Sahara’, these ties did not ‘establish any tie of territorial sovereignty between the territory of Western Sahara and the Kingdom of Morocco’ (§ 162). Morocco disagrees with this finding and feels that that the Western Sahara is legally and justly their territory since it used to be part of pre-colonial “larger Morocco”. See this Moroccan government website about the Western Sahara.

As I explained to the caller, in our report, we made a conscious choice not to get into this political and legal discussion. We made this choice, because this is not our research subject. We are not trying to decide who is the legitimate authority over the Western Sahara. There are many others who have written on the subject (e.g.: Okere (1979), Maghraoui (2003), Zunes (2015). Rather, we are trying to understand what the situation is regarding the child’s right to freedom of expression in this area, and what can be done to improve the protection of this right, by all actors involved. We want children, parents, teachers, politicians, NGOs and local community members to hear our message. If we would discuss the legal and political conflict over the territory, even if briefly, this would immediately become the centre of attention for most of our readers. Everyone would start discussing this part of the study, and very few would still pay any attention to what (else) children are not free to discuss. This would certainly not help the children living in this area at all.

In spite of these arguments, the question of whether or not to discuss the legal/political situation regarding (il)legitimate authority over the Western Sahara has lead to much discussion, with actors from both sides as well as within our research team. Does trying to stay neutral on this conflict, to be able to address a children’s rights issue, mean “siding with the oppressor”, as one of my colleagues suggested? Personally, I don’t think so. This is first, because we don’t use the preferred term of either parties (“Occupied Western Sahara” would be preferred by the Sahrawi activists, “Moroccan Sahara” or “Moroccan Southern Provinces” would be preferred by Moroccan nationalists). Instead, we use the UN term “West of the Berm”. Second, we don’t take a position, but we are critical of children’s rights violations happening within the territory, by all actors. Lastly, I don’t see how it would be necessary to first discuss whether or not Morocco’s position in the Western Sahara is legal, before we can discuss the situation of the child’s right to freedom of expression.

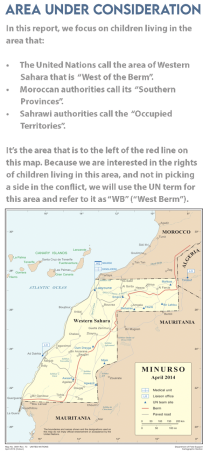

Report page where the area under research is discussed

SOURCE: UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations

Cartographic Section. (2014, April). UN map MINURSO-

deployment Western Sahara, April 2014 [Illustration].

Wayback Machine.

It doesn’t matter which side you agree with, because in any case, everyone should be free to voice their opinions.

Instead of siding with one of the conflicting parties, I choose to side with the children. The children who are not allowed to freely express their ideas.

In our study we found that children are not allowed to:

- Criticise or insult the Moroccan King and/or his family

- Discuss the Western Sahara, in particular the question of whether it is or isn’t Moroccan

- Question religion (Islam)

- Discuss sexuality outside of marriage and everything having to do with non-heterosexual preferences.

As you can read in our report (p. 10-15) different actors play a role in the limitation of this child’s right. The Moroccan state is an important, but not the only, actor limiting this right for children.

The other day I shared this thought with a Sahrawi contact: “I just hope everyone wants to read the report and forget about the conflict for a minute and think about what is best for children...”. He immediately replied: “It is very impossible for people here to forget about politics!”. I think he is right about that. And as I told him, I probably shouldn’t say “forget, but more like, for a minute not see that as the most important and only issue.”

I may be naïve to think that this is possible. I may be naïve to think that one day, all actors could create the space for children to freely discuss their thoughts. That children would be allowed to say so if they think the Moroccan King is a bad leader, or that they have homosexual feelings, or that they are not sure whether they believe in Allah. Or that they think Morocco should get out of the Western Sahara. I understand that with all these subjects there are many emotions, beliefs and experiences of injustices that make people particularly opposed to free discussion. Still, I think this is a right that children (and researchers!) should have. At least, when I explained all this to the young Sahrawi person who called me, he understood. And so there’s at least one person who has received our message.

By Marieke Hopman - 1 June 2021

We proudly present the draft report of our study on childrights to freedom of expression in area "West of the Berm" or Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara. Please read and tell us what you think via