One of the case studies in the research project on children’s rights in unrecognised States is the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), a State claiming the territory of Western Sahara, large parts of which are currently under control of Morocco. While the SADR government is mostly based in Algerian refugee camps, it also controls a strip of land of the Western Sahara territory. The SADR refers to this territory as ‘liberated territories’, which are separated from the Moroccan side of the Western Sahara by a huge sand wall and some remaining landmines, meaning that the only way to travel there is from the Algerian side. There is very little information about the children living there, so we decided that it was important for me to visit the area and try to get at least an impression of what life is like for children living in this remote area. However, doing research in such an area far into the desert involves many unforeseen challenges and turned into quite an adventure.

For starters, as a foreigner, you are not allowed by the SADR government to go on this trip unaccompanied. There are various security measures that you have to stick to, including being accompanied by military personnel at all times of the trip. This means that you have to (1) coordinate with the SADR authorities for which days they can arrange trips for foreigners to the ‘liberated territories’, (2) do the trip together with other foreigners wanting to visit the area, as there are limited security cars and staff members available, (3) have the driver and car that will be driving you authorized by the government. Just to get that done I had to go to the administrative centre of the camps three times, again requiring a driver and having him authorized to drive me.

Additionally, there was the cultural aspect of wanting to travel with our female translator so she could help with interpreting interviews with girls. I learned that in many Sahrawi families unmarried women cannot travel without a (male) family member for protection, especially for such a long trip. There was a lot of back and forth before we found someone who would agree to accompany her.

Of course, there were many other things that made the trip difficult or uncomfortable, such as there not being any internet and phone reception for me to contact Marieke and ask for advice, or simply the lack of sanitary facilities. The most challenging factor by far were the unreliable cars. Driving on such rough, largely uninhabited terrain makes you completely dependent on the car you are travelling with. Unfortunately, we did not only go through quite a collection of flat tires (perhaps unsurprisingly, seeing as there was no road), but after a 15-hour drive into the desert, the car in which our translators and I were travelling completely broke down. At least there was still space in the car of another organisation that was with us on the trip. At that point we only had one security car accompanying us left (the other one having broken down too), so the whole group had to move around together at all times, leaving me with little control over where we would go.

(2) With limited equipment and tools available in the desert, there was no way to get our car back to speed for driving us back.

This is definitely not ideal if you are trying to find children that you can interview anonymously in an extremely sparsely populated area. Everyone in the group of foreigners that we were with was from different organisations and had different locations that they wanted to head to. I had the strong feeling that my agenda was not being taken into account by the security staff planning our itinerary. There were times where I did not know whether we would be able to do any interviews at all, which I found quite stressful because I did not want to see all the money and time spent on this trip wasted. At this point, I decided to explain again very clearly what we were here to do and, in the end, two primary school visits were arranged, and we got to do several interviews with children there. I was very relieved, and very exhausted.

While all this was quite an adventure, I think it was important to get some insight into what the area looks like and what children living in the ‘liberated territories’ experience, although I wish that we could have done more. Still, I think that the fact that it was so difficult to get there and get interviews done just makes it even more important that we tried.

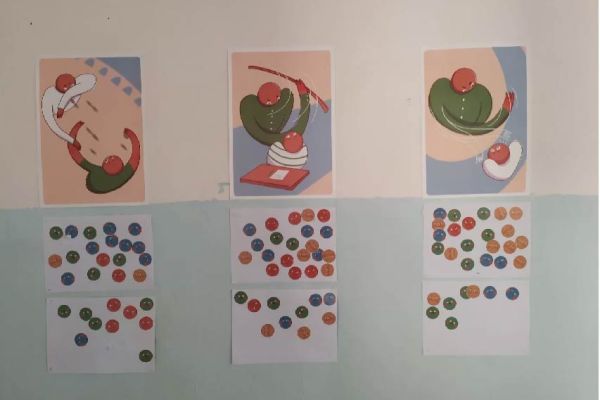

(3) Children playing after classes at a primary school in the liberated territories.

(4) Getting from the camps to the inhabited strips of land in the liberated territories is an approximately 15 hour drive, so this was my view for the biggest part of the trip.

(5) Stopping on our way for a lunch of camel meat.