Introduction

Fleeing from the conflict in Western Sahara in 1976, many indigenous Sahrawi nomads fled to the neighboring Algeria and settled near the Algerian town of Tindouf. Ever since, the refugee camps near Tinduf have been home to thousands of Sahrawi refugees and have been controlled by the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). While there is much to write about the history and life in the Tindouf camps, in this blog post, I will focus on the question on whether parents are allowed to lightly spank their children in the camps.

However, researching about children’s rights in ‘self-governing’ refugee centers, such as the Tindouf Refugee Camp, is not an easy task. These camps are governed by SADR, but it is neither recognized as a sovereign state nor can become a member to international conventions, such as the “Convention on the Rights of the Child” which prohibit any type of physical punishment of children. The answer of the question “what law is applicable and who is responsible in such areas in relation to the protection of children’s rights would not be straightforward. In this post, I will therefore look into different potentially applicable laws to find out whether parents are (legally) allowed to physically punish their children in the Tindouf refugee camps.

Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) law

Algeria, the host state of the Tindouf camp, delegated all responsibilities over the camps to the Polisario government. This means that in the camp, Sahrawi law is practiced. Leaving aside the issues that arise due to the lack of international recognition of SADR as a state and therefore the legality of its legislation, researching about children’s rights in the camp is accompanied with the difficulty of accessing the SADR legislation. While references to the Family Code, Civil Code and Criminal Code can be found, I was unable to access any of those sources and could base the legal analysis only on the Constitution.

Unsurprisingly, there is no provision in the constitution that prohibits physical punishment of children, especially not at home. However, some potentially relevant rules are:

- The family is the foundation of the society and should be based on religious, ethical and national values and on the historical heritage (Article7)

- The protection and promotion of the family values is the obligation of the parents, especially regarding the education of their children (Article 50)

- It is prohibited to violate anyone’s sense of morality or honour or to exert any kind of physical or moral violence against another or infringe their dignity (Article 28)

- Special protection is to be given to mothers, children, disabled persons and the elderly and the state has to set up institutions to that end and enact relevant laws (Article 39).

A map of the territory of Western Sahara and the Tindouf camps.

SOURCE: The Public Broadcast Service

At first sight, this could be understood to mean that physical punishment is not allowed, as it is prohibited to exert any kind of violence against another or infringe their dignity. Additionally, children are supposed to be under special protection. This reasoning would be in line with the international law. However, without being able to access the family or criminal codes, it is impossible to establish whether there is an explicit prohibition of physical punishment of children at home. Even if such a prohibition exists, the question remains whether such legislation is accessible to parents in the camps and if parents would be aware of such a prohibition.

International and regional law

As an unrecognized state, the SADR is not a party to international treaties such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child. It signed but did not ratify the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACRWC). Therefore, the statement of the African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, body responsible for supervising implementation of the ACRWC, which established that physical punishment is not allowed under ACRWC, has no legal effect in SADR. This means that under international and regional law, the SADR has no obligation to prohibit physical punishment at home.

Sharia law

Islam, as the predominant religion of the Sahrawi, plays an important role in the Tindouf camps. Moreover, according to the Sahrawi Constitution, Islam is the State religion and the main source of law (Article 2).

Sharia law (Islamic law) has multiple sources, namely the Holy Book (The Quran), the Sunnah (the traditions and practices of the Prophet Muhammad), Ijma' (opinions of Islamic scholars), and Qiyas (analogical reasoning based on principles deducted from the Qurʾān and the Sunnah). Due to the nature of these sources, the exact content is subject to interpretation. As a consequence of these different interpretations, there are divided views with respect to whether physical punishment of children at home is allowed.

Two main views are that (1) parents or guardians should refrain from physical punishment and use other disciplining methods instead, and (2) that physical punishment is allowed in certain instances. The second view is dominant and according to this interpretation of Sharia law, parents/guardians have to follow certain rules if they want to physically punish their child. I was able to identify following rules:

- The parent should use firstly other types of parenting methods, such as direction, kind warnings and advice.

- Children under the age of ten should not be beaten

- The punishment with beating should be appropriate to the misdeed

- The beating should not hurt the child either psychologically or physically

- Parents/guardians should beat only in a suitable setting, meaning not in front of other people.

- The child should not be beaten when the parent/guardian is angry. Both the parent and the child have to be aware that the beating is required for discipline, not for revenge or torture.

- The child should not be beaten in delicate places such as the face or private parts.

Nonetheless, not all rules are not always recognized with same importance and everywhere, and while some (such as the rule that parents have to use other means of upbringing first) are generally accepted, others are more disputed.

Algerian law

As Tindouf Refugee Camps are located within the Algerian borders, it is also important to consider Algerian law. Algeria ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and the African Charter on Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACRWC), both providing that physical punishment at home should be prohibited. According to Algerian Constitution, those conventions are superior to national law and can be invoked before national courts with superior authority to national legislation (Article 132 Algerian Constitution). This means that if national law is not in line with one of the conventions, the national court will set aside the national law and apply the Convention.

In 2015 the Algerian penal code was amended and some forms of domestic violence were prohibited. Some of those newly prohibited acts are:

- intentionally injuring or beating a minor under sixteen years,

- preventing the minor from food or care to the extent that the minor’s health is exposed to harm,

- or any other act of violence against a minor. (Article 296 Penal Code)

However, acts that cause ‘light harm’ and result from actions of parent’s methods of disciplining a child are not prohibited and are considered to be part of the parents' fulfilment of their responsibilities towards the child in raising it and correcting its behaviour. Therefore, actions such as light spanking, are allowed.

But what constitutes light harm? Where is the line to be drawn between physical punishment allowed to discipline the child and violence? The answer is: it depends. Several factors such as the age and maturity of the child as well as other surrounding circumstances have to be taken into account. Allowing acts of light harm gives courts and social care institutions flexibility to examine each case on its own merit. However, such a rule leaves a discrepancy between international law that Algeria is bound by, namely the CRC and the ACRWC, and national legislation.

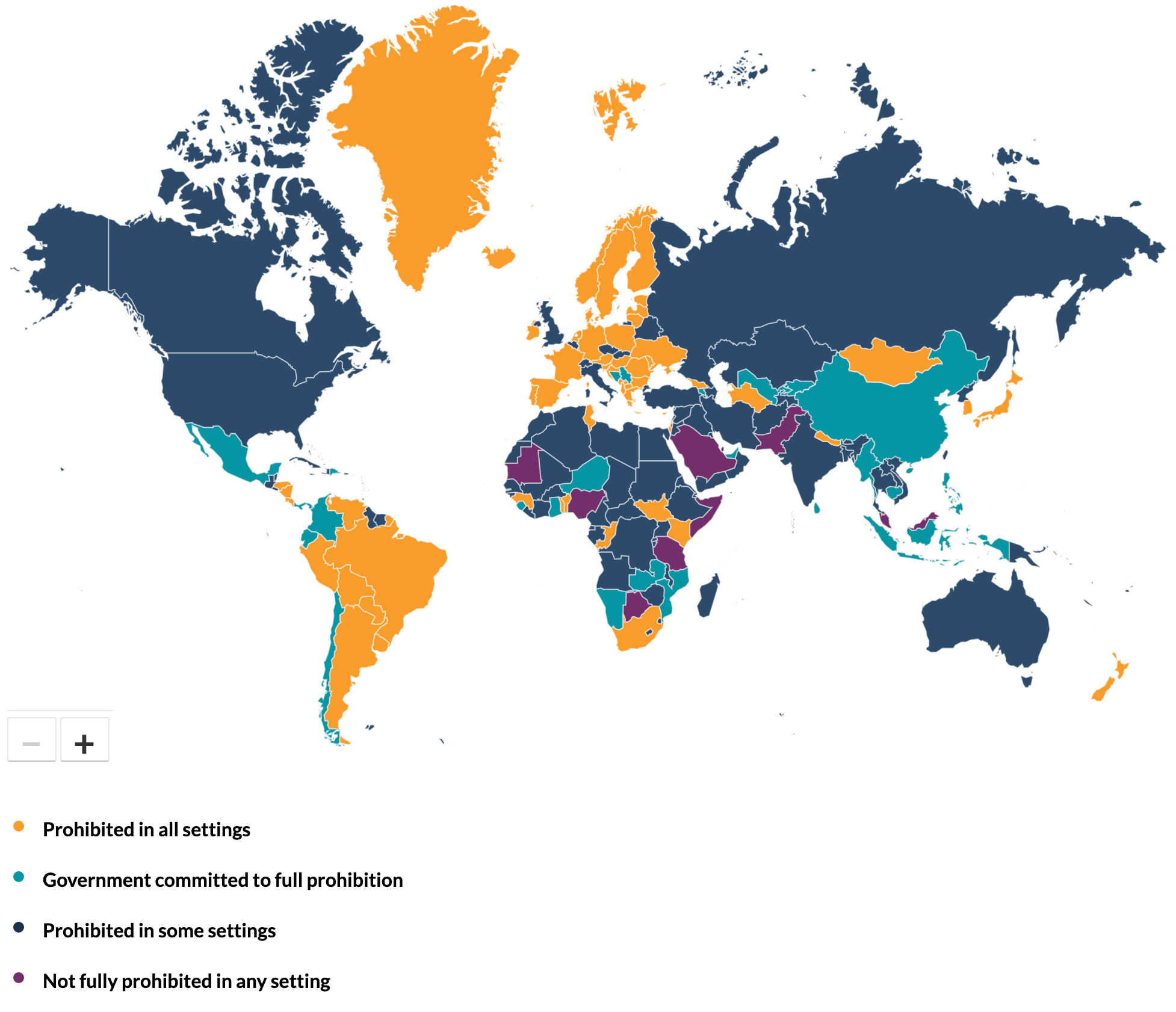

Corporal punishment per country

SOURCE: End Corporal Punishment. (2021). Detailed report on corporal punishment per country [Interactive map]. End Corporal Punishment.

Conclusion

Are parents legally allowed to physically punish their children in the Tindouf camp? While in situations where parents inflict serious harm by using physical punishment it is easy to establish that such punishment is considered violence against the child and is prohibited, when talking about acts such as light spanking the answer is ‘it depends’.

It is conditioned upon which law you think is most relevant. If you consider SADR law relevant, such punishment is allowed. However, given the important role Sharia law play, both in the Sahrawi population in the camp and under SADR law, it would seem that physical punishment is allowed only if certain rules are respected. On the other hand, if you believe Algerian law is applicable, physical punishment would seem to be allowed as long as it only causes light harm. However, as Algeria is bound by both CRC and ACRWC that prohibit any type of physical punishment, and as such international conventions have ‘priority’ over national law, it could also be understood that no physical punishment is allowed.