Introduction

When conducting our research on the rights of the children in the Tindouf camps, we encountered the question whether parents are (legally) allowed to physically punish their children.

One of the universal human rights of every person, including every child, is to be protected from violence. But does light spanking by parents to ‘teach a child a lesson’ qualify as violence? And if not, where is the line to be drawn between physical punishment of the child that is allowed and violence against the child? Or is physical punishment by parents not considered violence at all?

Disciplining a child can be difficult and parents opt for different methods of disciplining their children. One of the oldest methods thereof is physical punishment, which nonetheless is becoming subject to increasing criticism. But what is the legal view on physical punishment of children?

While in most countries physical punishment (also referred to as corporal punishment) in certain settings is illegal, such as in school, care centres and detention, the number of countries prohibiting such punishment at home is significantly lower. As it would be impossible to analyse the law of all states in this blog, the question whether parents are allowed to lightly spank their children will be examined in light of international and regional children’s rights law.

1. International children’s rights law

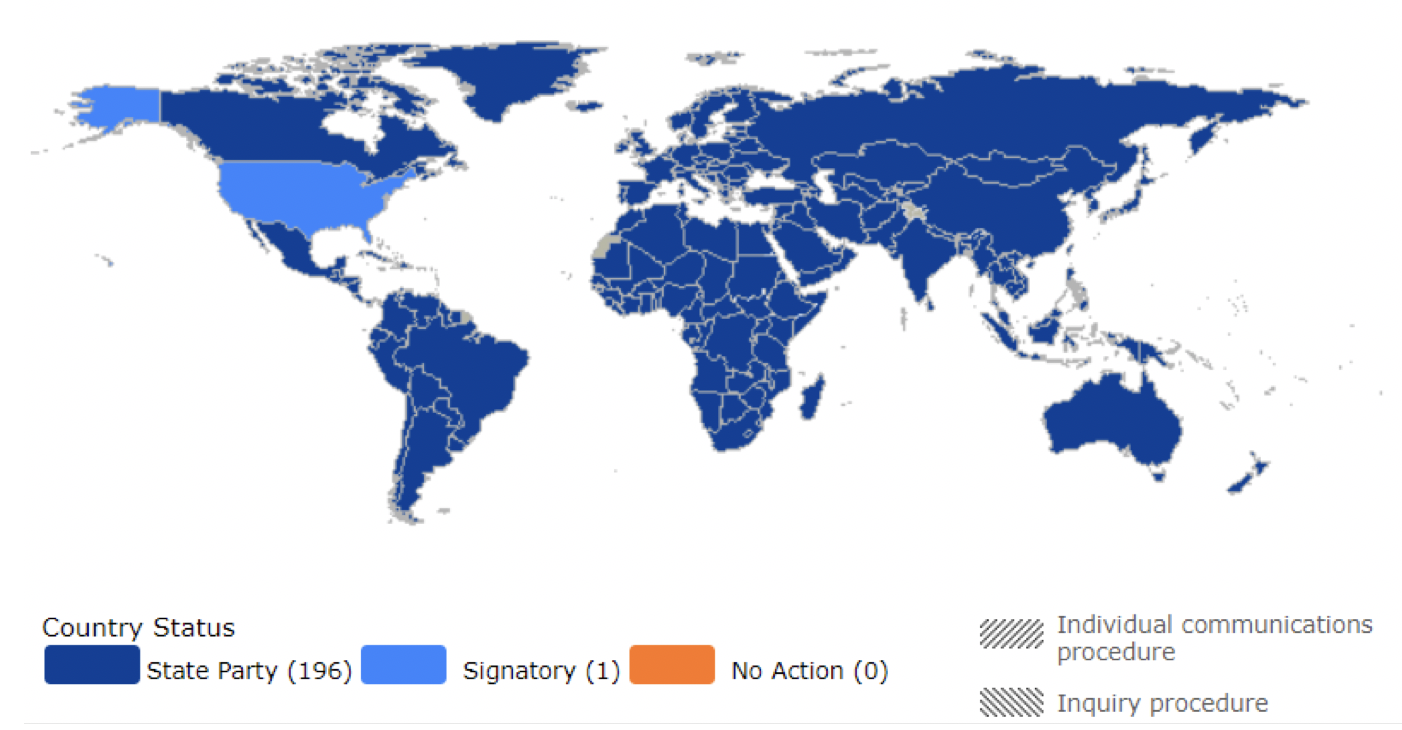

The most important international children’s right instrument is the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). All countries in the world except United States have signed and ratified this Convention.

According to the CRC, states need to:

- take measures to protect children from all forms of physical and mental violence (Article 19)

- take measures to abolish traditional practices that may harm the health of children (Article 24(3))

- ensure that disciplinary measures at school respect the child’s human dignity (Article 28(2))

- ensure that children are not subjected to torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (Article 37(a)).

State parties to the CRC

SOURCE: Human Rights Indicators Work. (n.d.). Ratification of 18 International Human Rights Treaties [Interactive map]. United Nations Human Rights.

However, the CRC is a living instrument, meaning that its content should be interpreted and adapted to changes and developments in the society. And, while it does not explicitly prohibit physical punishment of children, the Committee on the Rights of the Child (whose role is to monitor the implementation of the Convention) stated in General Comment No. 8 that the Convention requires states to prohibit and eliminate all corporal punishment, including in the home. This means that any punishment in which physical force is used and intended to cause some degree of pain or discomfort, however light, is prohibited. While the General Comment is not legally binding, it is an authoritative soft law document clarifying the obligations of States under the CRC.

Moreover, other important human rights bodies, such as the Human Rights Committee, the Committee Against Torture, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, all made recommendations to states to prohibit all physical punishment of children, including that at home.

2. Regional international children’s rights law

2.1 African Charter on the Welfare of the Child

Similar to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACRWC), ratified by 49 African states, aims at protecting children from violence. But does this include physical punishment?

The Charter requires states to undertake measures

- to protect children from all forms of torture, inhuman or degrading treatment and abuse (Article 16),

- to ensure that school’s or parental discipline respects the child’s inherent dignity (Article 15),

- to ensure to the maximum extent possible, the survival, protection and development of the child (Article 5).

The Charter does not only impose obligations on the states, but also on parents, who have to ensure that domestic discipline is exercised with humanity, and that it respects the dignity of the child (Article 20).

The African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, which supervises the implementation of the ACRWC, in their statement on violence against children, held that physical punishment of children should be publicly condemned and eradicated. They also require states to adopt laws that prohibit all corporal punishment of children in all settings including the home, and for states to put in place implementation measures to achieve effective protection of children. According to the committee, custom, tradition, religion or culture cannot justify harmful cultural practices such as physical punishment.

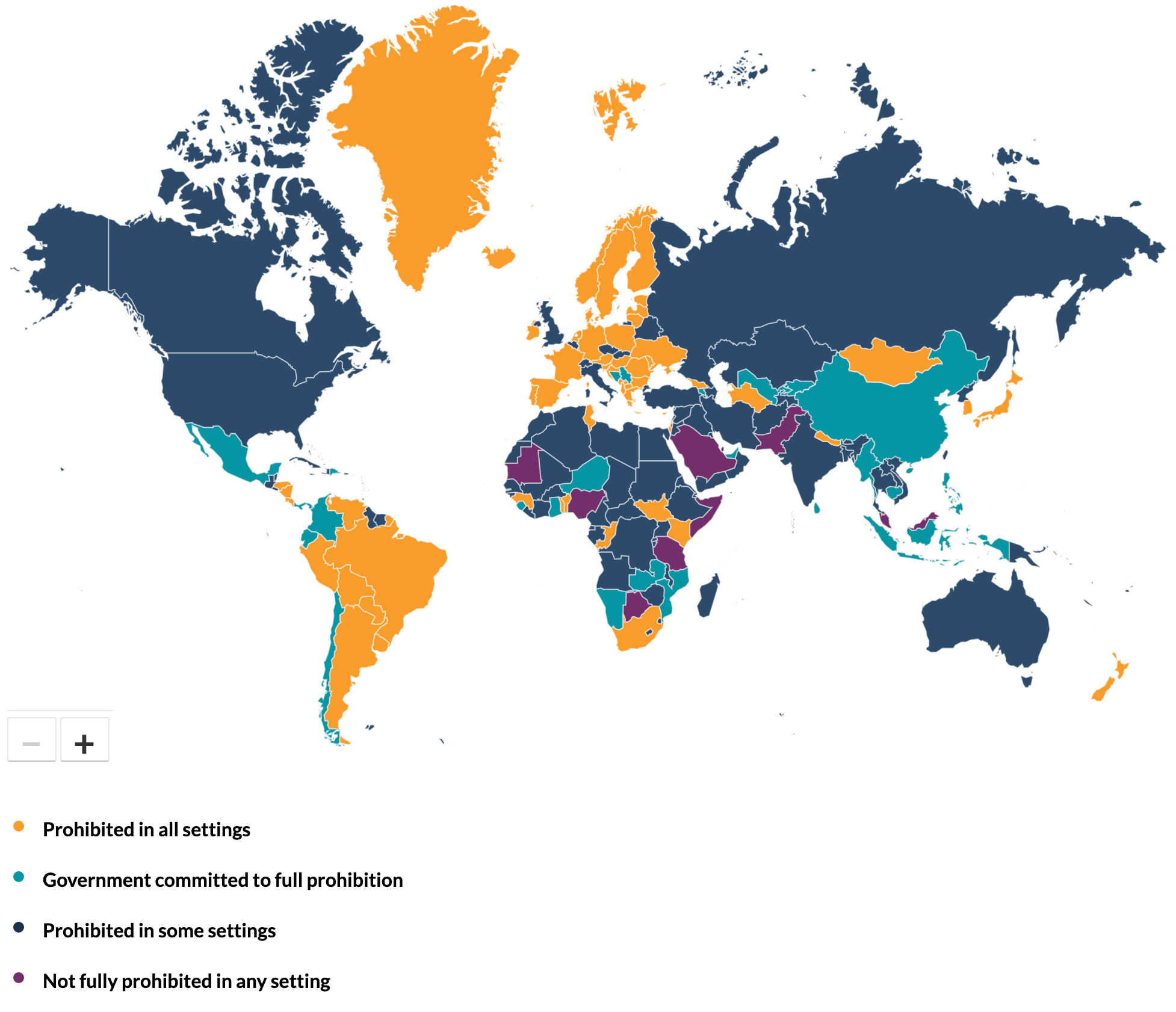

However, the implementation of such a prohibition varies across African countries, and while some have prohibited physical punishment of children in all settings including that at home (such as South Africa, Kenya, South Sudan and Tunisia) other countries have not fully prohibited physical punishment in any setting (such as Botswana, Tanzania, Mauritania and Nigeria).

Corporal punishment per country

SOURCE: End Corporal Punishment. (2021). Detailed report on corporal punishment per country [Interactive map]. End Corporal Punishment.

2.2 Europe

Unlike in Africa, in Europe there is no convention or charter specifically aimed at protecting children. This means that in European human rights law, there is no single provision that explicitly prohibits corporal punishment of children.

However, this does not mean that physical punishment of children at home is allowed. Why so? Children bear the same rights as adults under regional human right’s instruments; the European Convention on Human Rights and the European Social Charter are particularly relevant in this regard.

2.2.1. European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)

Physical punishment of children is not allowed under the ECHR, a convention that all European states are party to and that guarantees fundamental civil and political rights. This prohibition was developed through judgments in the legal cases of the European Court on Human Rights (ECtHR), which uses the ECHR. The Court first ruled on physical punishment in 1978, on a case concerning physical punishment at school: Tyrer v. the United Kingdom. In this case the Court ruled that such punishment is in breach of Article 3 of the ECHR which prohibits torture, inhuman and degrading treatment and punishment.

In 1998, the ECtHR for the first time addressed a case of physical punishment at home.

The case, A v. UK., was brought by a little boy who was hit with a cane by his stepfather. Initially, when the case was first discussed in national UK courts, the stepfather was under the defence of “reasonable chastisement”, and the national courts found that such physical punishment was allowed to discipline a ‘difficult child’. However, the ECtHR disagreed. They ruled that allowing for physical punishment at home was contrary to the prohibition on torture, inhuman and degrading treatment and punishment (Article 3 of the Convention), and concluded that this includes the prohibition of physical punishment of children in all instances.

However, a prohibition of physical punishment at home often encounters resistance in the society. Let’s take for example Sweden, which was the first country to prohibit physical punishment of children at home, already in 1977. The reaction to the ban was divided, and some parents believed that such ban interferes with their right to private and family life and freedom of religion. Some parents even brought the matter in front of the European Commission on Human Rights, the ECtHR predecessor. Nonetheless, the Commission found that such a ban neither interferes with the private and family life, nor freedom of religion, and held the case inadmissible. In such way, the Commission paved the way for other European states to implement a ban on physical punishment of children at home.

2.2.2 European Social Charter (ESC)

Physical punishment of children is also prohibited by the European Social Charter which guarantees fundamental social and economic rights and which applies to all European states.to which all European states are party to. Article 17 of the ESC requires states to protect children and young persons against negligence, violence or exploitation and encourage the full development of their personality and of their physical and mental capacities.

The Committee stated that states are required to create law that is sufficiently clear, binding and that specifies the prohibition of any form of violence against children, including physical punishment at home. (see this case).

2.3 Other regions

Outside of Africa and Europe there is no regional law prohibiting physical punishment.

While the Inter-American Court of Human Rights rejected the request by Inter-American commission on Human Rights to issue an advisory opinion on physical punishment of children, the Court did argue that “children have rights and are an object of protection”, that they have the same rights as all human beings, that the state must protect these rights in the private as well as the public sphere, and that this requires legislative as well as other measures.

While not binding, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights issued a Report on Corporal Punishment and Human Rights of Children and Adolescents recommending states to prohibit all physical punishment of children, including that at home.

In North America, physical punishment of children remains legal. However, in Latin America most countries have specific legislation prohibiting such punishment, at home including Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Costa Rica, Honduras, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela.

In Asia, there is no regional law concerned with physical punishment of children, and whether physical punishment of children at home is allowed, depends on the national law of different Asian countries.

3. Conclusion

Is it allowed to physically punish your child? Under international and, where applicable, regional children’s rights law, the answer would be no. Such punishment, regardless of how light or severe, is illegal according to the Convention on the Rights of the Child and regional instruments such as the African Charter on the Welfare of the Child or the European Convection on Human Rights. However, this legal prohibition on the international level is not always reflected in national laws. Sometimes it is even contradicted by national laws explicitly allowing for physical punishment of children. Therefore, in reality the legal situation remains different due to the discrepancies existing across different national laws.

If you are interested in what this means when talking about unrecognized states, look into our next blogpost where we will examine whether parents are allowed to use physical punishment as a way of disciplining their children in the Tindouf refugee camps.