Since the start of our project in 2019, four de facto states got involved in armed conflict. We argue that this shows that children living in de facto states deserve more attention from the international community (rather than less, as is currently the case).

A de facto state is a state fully function as any other state, with a population, government and a territory, yet they are not United Nations member states. Children living in de facto states fall outside the scope of international legal protection. Generally, governments of de facto states are not allowed to sign and/or ratify international legal conventions (with Palestine as the only exception), and international human rights law does not apply to de facto states. Children living in de facto states receive little (if any) attention in international bilateral and multilateral fora. Development aid cannot be channeled to most de facto states, or only with great difficulty. The rights of these children are often not protected in practice by non-governmental organisations and UN organisations, for whom working in these areas can be particularly challenging. Lastly, the situations of these children are generally under researched. Our project that studies the development rights of children living in de facto states, is the first project to do so.

All de facto states are subject to political conflict. This is part of the reason why they are de facto states: because there are other states that claim the same territory, and as a result of political and sometimes military actions, they cannot become UN member states. So while these de facto states fully function as states (with a population, government and a territory), they are not fully recognised as states, and the people living in de facto states suffer political and economic consequences of their countries’ disputed status. For example, some de facto states are under economic embargo, so that it is very difficult for people living in these areas to engage in international trade. Politically, they are under constant threat of annihilation, if the state who claims the territory chooses to reclaim the territory through military means. Such developments we have seen recently.

Since the start of this project in 2019, four de facto states who are part of our project became involved in an armed conflict. First, in 2020, the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) restarted their war against Morocco over the territory of the Western Sahara that is currently under Moroccan control. This happened after a 29 year ceasefire had been in place, yet the promised referendum for self-determination had still not materialised, and nothing had improved for the Sahrawi refugees in camps in Algeria. Second, in February 2023, armed conflict broke in the Los Anod region of Somaliland between the Somaliland state army and local Dhulbahante militias. Although the conflict is currently at low intensity fighting, children are still at grave risk. Third, also in 2023, after nine months of blockade of the main supply route, Azerbeijan attacked Nagorno-Karabakh, claiming the territory. In this case, the military power of Azerbeijan was overwhelming. All children living in Nagorno-Karabakh have moved to Armenia, and per 1 January 2024 Nagorno Karabakh seizes to exist. A few weeks later, Hamas attacked a group of Israeli near the Gaza border, and this started a war between Israel and Hamas which has only just begun. The attack by Hamas (and their holding of hostages, including children), provoked an extremely severe military reaction by Israel, who are heavily bombing Gaza and do not allow for humanitarian aid (including food, water, fuel and medical supplies) to be delivered to the area. UNICEF warns that “time is running out for children in Gaza”.

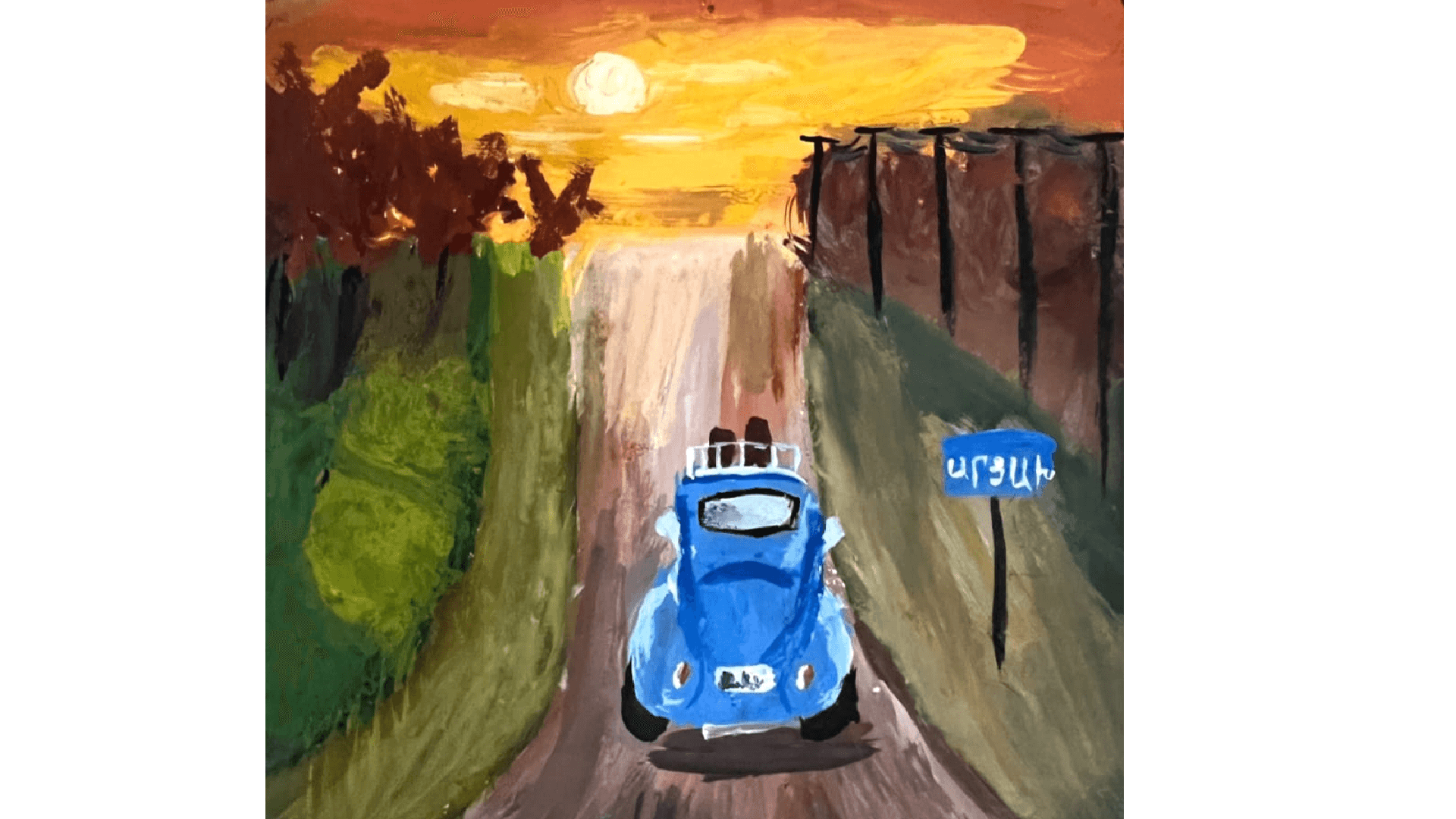

"We exist," by Ridwan (14), Somaliland.

Zooming out of the recent catastrophes, these developments show that children living in de facto states, no matter their ethnicity, nationality, religion or political affiliation, are subject to very vulnerable circumstances. Today and any day. As one child in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) told Marieke in 2017:

"It hurts when I am growing [up] because all dreams that you have are limited […] you can’t really evolve roots because something might come up, like a [political] solution that will change the whole game."

This is the situation in which children in de facto states live, in times of war and in times of peace. The recent events show that children living in de facto states deserve MORE attention from the international community, instead of less.

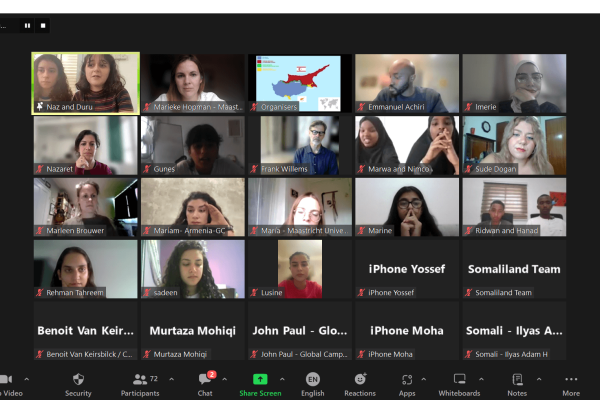

On 28 October 2023 16.00h CEST, children from different de facto states (Palestine, Nagorno-Karabakh, Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, Somaliland, Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus) will share their stories in a child-led online event titled “Children in de facto states: We want to share our stories!”. If you like to join, please sign up here.