Why measure?

Twice this millennium, world leaders have come together to pledge to erase global poverty and launch an agenda filled with measurable targets to monitor their progress. This is not so much special because of the pledge itself (world leaders tend to make all sorts of lofty pledges when they get together), but rather because they choose to monitor their progress. The Millennium Development Goals – and their successor the Sustainable Development Goals – break down the overall goals in several sub-goals, and attach multiple measurable targets to each of these. The SDG for education, for example, has as its target that by 2030 all boys and girls complete “free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education”, which is measured by the proportion of children in grades 2/3, at the end of primary, and at the end of lower secondary with at least a minimum proficiency in reading and mathematics. Having such goals allows us to track development progress, both over time and in comparison with other countries. It is bad press if you as an education minister manage to have fewer children in school than your predecessor, or in comparison with your (otherwise very comparable) neighbouring country. Having measurable goals thus increases accountability.

How to measure?

In my PhD research (A quantitative approach to the right to education: concept, measurement, and effects, 2021), I applied a similar reasoning to the human right to primary education. Compared to development goals, human rights have the added value of carrying greater moral weight, and of being legally enforceable obligations. Making human rights comparable should thus increase accountability even more! Measuring human rights is easier said than done, however. Do we check if the right is present in the law, or if the intended outcome of the right is achieved? And what about the process by which these outcomes are achieved? In the end I settled on measuring whether the right is present in the law, as codification is a sine qua non for rights protection.

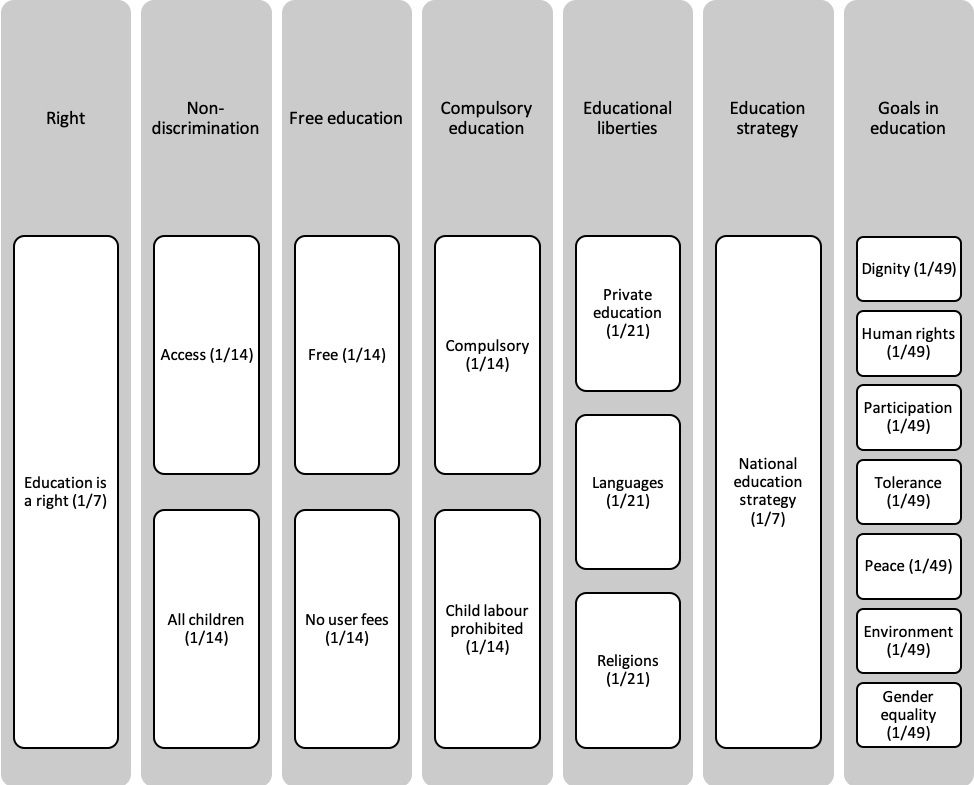

This choice is only the first of many in the measurement process. The next question is about what exactly is understood by the right to primary education. We opt for the minimum core obligations, a set of seven elements that set the minimum floor of what should be the right to education. Other notable dilemma’s include what to do with progressive realisation, how to handle potential violations of the right, as well as the countless small choices you need to make when capturing complex legal language in a limited set of numbers. In the end we designed a right to education index, in which the seven elements are divided into 18 indicators. This index allows us to score a country’s education legislation on a scale from zero to seven, with a higher score denoting a better legal protection of the right to education (see figure).

What did we find?

Using this index, we scored 45 countries in sub-Sahara Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean for a period of 29 years. The good news is that the legal protection of the right to primary education has increased substantially over that period, and did so for all its elements. In 1990, for example, only 28 (of the 45) countries mandated compulsory primary education, compared to 41 in 2018. Only two countries (Ethiopia and Equatorial Guinea) had a worse score in 2018 than they had in 1990. Exhibiting a positive trend is not the same as fulfilling the right to education, however. Only two countries (Honduras and Cameroon) managed to completely fulfil their legal obligations vis-à-vis the right to primary education, and only towards the end of the study period. This is a concerning outcome, given that we are measuring the minimum core obligations, that are considered to be the absolute minimum floor of rights-protection. Going below that essentially means that there is no right to speak of. Keep in mind that I only measured the legislative part of the right, and it is difficult to see how states can meaningfully protect these rights in practice if they cannot even manage to legislate their absolute minimum sufficiently.

This relationship between the right as law and the right as outcome was the final part of my dissertation. We empirically tested if changes in the legal status of the right had an effect on the percentage of children enrolled in primary education, as well as the percentage of children completing said education. We found a delayed effect, where both outcomes improved significantly about seven to nine years after the legal change. Governments committed to improving the right to education are thus in it for the long haul, with progress likely only becoming visible after their tenure is already over.

Reflection

When you take a helicopter view of the research, there is reason for optimism, but there is also reason for caution. It is positive that the legal protection has improved over the last thirty years, but it is worrying that almost no country has fully legislated the minimum core obligations. On the other hand, meaningful improvement in outcomes is possible as a result of (relatively) small changes in the legal framework. This does take long-term commitment, however. The dataset created by this research allows us to monitor the legal progress, and correlate it with right outcomes. It is thus a useful tool in the continuous effort to hold governments accountable for their promises to improve the wellbeing of their people.

Lastly, a word of warning. The process of measuring human rights required a myriad of choices. While all these choices were given careful consideration, it is not inconceivable that another team of researchers would have made other choices along the way. I thus highly recommend any users of the data to treat it as the starting point of a discussion about the right to education, rather than the end of it. Still interested? You can find the data here, or

https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal4

Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, 1999, General Comments 11 and 13.

Argentina, Barbados, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Cabo Verde, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Colombia, the Comoros, Costa Rica, Côte d’Ivoire, Cuba, Ecuador, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Guyana, Honduras, Jamaica, Kenya, Lesotho, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mexico, Mozambique, Namibia, Nicaragua, Niger, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, the Seychelles, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, São Tomé et Principé, South Africa, Togo, Trinidad and Tobago, Uruguay, and Zambia.

Alston, P. (1987). Out of the Abyss: The Challenges Confronting the New U.N. Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Human Rights Quarterly, 9, 332