I would like to start this blogpost with a quick thought experiment. First, I want you to imagine the most difficult emotional experience you endured as a child. Then ask yourself: What helped you to cope? What made you feel worse? The answers to these questions are known in psychology respectively as protective and risk factors. Such factors play an important role in determining how we process and recover from traumatic events.

According to Save the Children, around 449 million children – or one in six children – worldwide lived in a conflict zone in 2021. Targeted interventions utilising research findings on protective and risk factors for psychological harm due to experiences of political violence can play a vital role in helping these children who, from Yemen to Ukraine, are at risk of being traumatised by growing up in a conflict zone. In autumn 2022, I participated in a team from Maastricht University that conducted field research concerning the rights of Israeli children living in the West Bank. This research found that these children are particularly at risk for being exposed to political violence. This got me thinking about what can be done to reduce the psychological impact of this conflict on the children living there. As such, this blog post reviews the academic literature on risk and protective factors to see what the effects of exposure to political violence might be for children living in the West Bank, and how these research findings could be used to minimise the psychological harm it can cause.

In the first part of this blogpost, I summarise the key research findings from this field. In the second part, I briefly consider impactful policies that can be developed from these findings.

Psychological consequences of political violence

Young people are particularly at risk for negative psychological outcomes if they experience political violence. This is because children and adolescents are still developing their ability to regulate their emotions, forming a sense of independence, and establishing their relationship patterns. However, not all young people are equally affected. On the one hand, research shows that experiencing political violence increases a person’s risk of being diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, depression and anxiety and can lead to behavioural, psychosocial, and emotional problems for children. On the other hand, some children experience mild or no psychological consequences at all. To explain these differences, researchers have looked for factors in young people’s backgrounds, demographics and social environments that may be acting to either increase the risk of or protect them from psychological harms.

Research on risk and protective factors

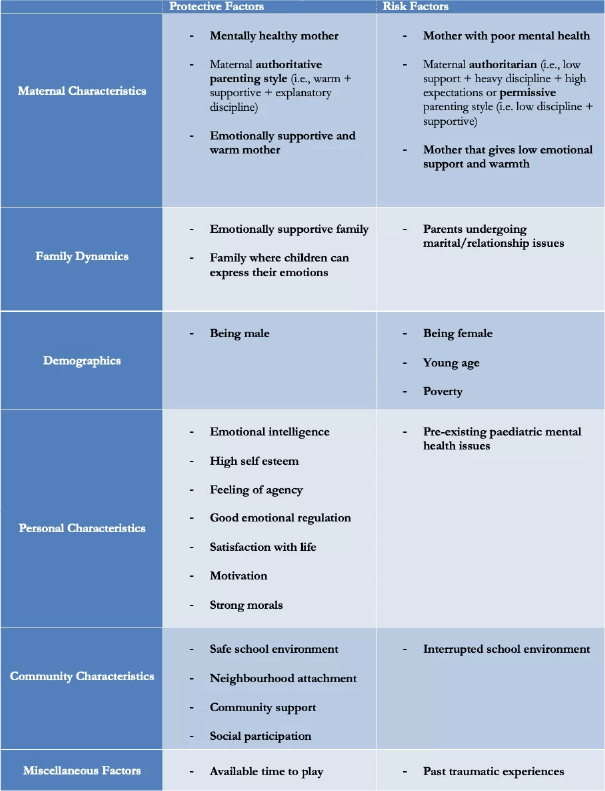

In this table, I list the key factors identified by researchers as either protecting or exacerbating psychological harms to young people who have experienced political violence. The studies and literature reviews cited below examined various age ranges of 0-18-years old living in areas exposed to chronic, intermittent and one-off incidents of political violence, such as: Ashkelon (Israel), Southern Israel, Palestinian refugee camps in West Bank and Gaza, Palestine and Israel, Lebanon, New York (post 9/11) and Iran, Northern Uganda, Rwanda, Kosovo, Georgia, Columbia and Nigeria.

How to use this information?

The risk and protective factors displayed above show that there are many factors in a child’s life that can increase or decrease the likelihood of negative or positive psychological outcomes, following exposure to political violence. As such, it is important to develop holistic interventions that target multiple areas of a child’s life and, moreover, the wider community, including the parents and extended family.

Identification of risk and protective factors can also help policymakers and childcare specialists (e.g., doctors and therapists) identify children who are most at-risk of suffering from psychological trauma and therefore in most need of support. For example, because prior trauma is a risk factor for negative psychological impact, children in areas of chronic political violence – who suffer repeat exposure to such events – are likely to be at higher risk.

However, in practical terms, some risk and protective factors may be easier to target than others. For example, while explanatory style of parenting is considered a protective factor it may be time-consuming and difficult to change parenting styles in places of chronic political violence. Thus, policymakers will have to make decisions based on research findings, but also pragmatically based on where, and to whom, the interventions will be delivered.

Protecting children in the West Bank from psychological harm

What do these research findings mean for children living in the West Bank? Firstly, children living in the West Bank should be considered at high-risk because the conflict there is among the most entrenched in the world. This means they are likely to experience repeated exposure to political violence, which increases the chances of negative psychological outcomes. Secondly, because these children are at high-risk, the best type of intervention to deliver would be a holistic one that targets several of the factors shown by research to increase young people’s resilience to traumatic experiences. Areas that interventions could target include creating a supportive familial and communal environment. However, implementing interventions in areas of ongoing political violence, like West Bank, is challenging. As such, the case study of West Bank underscores a major challenge faced by clinicians, researchers, and policymakers: those in most need of support to increase their resilience are often the most difficult to reach.

A playground in an Israeli settlement in West Bank. Time to play is a protective factor for children who experience political violence. Photo by Maastricht University researcher