Every child has certain universal human rights that should always be protected, right? But who is supposed to grant them these rights and afterwards protect them? Normally, states are responsible for protecting the rights of children living in their territory (whether they are citizens or not). But what if a state delegates this responsibility to somebody else, or if a state is not recognised by the international community? An example of such a situation can be found in the Tindouf refugee camps in Algeria. The camps are governed by the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), but not every state accepts that this Republic is a proper country. This also means that it cannot become a member to international conventions, such as the ‘Convention on the Rights of the Child’. That is why when writing my bachelor thesis, I decided to look at this situation a bit more closely and explored the research question ‘Who is responsible for the international human rights of Sahrawi people living in the Tindouf refugee camps?’. In this post I will focus specifically on children’s rights.

Context – The Tindouf Refugee Camps

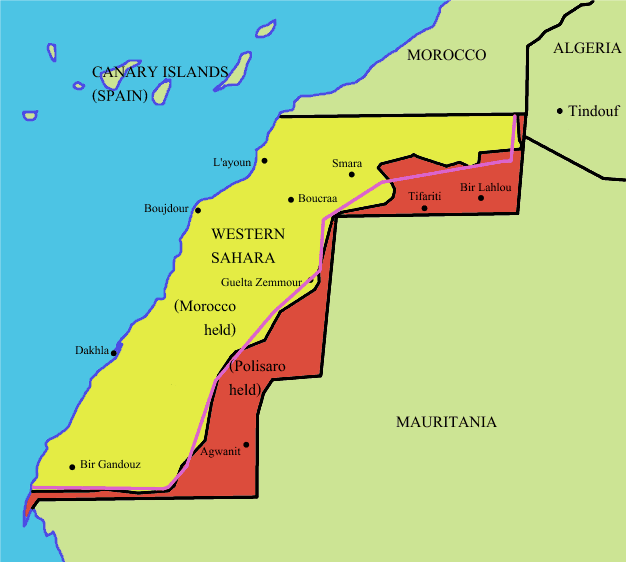

Of course there is a lot to I could say about the history of the Tindouf camps, but essentially what is relevant for this blog post is this: The people living in the Tindouf refugee camps are members of the ‘Sahrawi people’, a nomadic people from Western Sahara. When the territorial conflict about Western Sahara erupted into violence in 1976, they fled just across the border to the Tindouf area in Algeria. The United Nations refugee agency UNHCR has recognised that the Sahrawi people living in the Tindouf camps have the legal status of being refugees. The camps are controlled by Polisario, the liberation movement of the Sahrawi people, which is fighting for the Sahrawi’s claim to the territory of Western Sahara. In 1976, the Polisario proclaimed the SADR as an independent state, which is considered an unrecognised state. Although quite a few countries, as well as the African Union, recognize the SADR, not all countries do and therefore it is unable to sign most international treaties. Therefore, the camps are inhabited by a population of refugees that lives under what most of them consider their own government, but others consider to be an unrecognised entity, not bound to respect children’s rights.

The Issue – Non-State Actors and Why They Matter

Usually, when considering who is responsible for someone’s children’s rights, we turn to the state that is in control of the territory or the children in question. In the case of refugees, the international legal system sets out that the state which they are in must guarantee the refugees the same rights as its nationals.

This means that according to the existing framework Algeria, as the camps’ host state, is considered the primary actor in this scenario. It also has ratified various conventions, including the ‘Convention on the Rights of the Child’ (CRC) and the ‘1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees’. This means that Algeria has responsibilities such as treating nationals and refugees alike when it comes to access to elementary education and other public services. At first sight, the situation is therefore quite clear, Algeria is responsible for the international children’s rights of the Sahrawi children living on its territory, right? Yes, but…

From early onwards, Algeria has delegated all responsibility over the camps to Polisario. They recognize the SADR as an independent state, and the Polisario as its government. This means that Algerian authorities are not present in the camps and do not, for example, provide education in the camps. It happens surprisingly often that people find themselves in a situation in which not a state, but another type of actor is making the calls when it comes to their children’s rights protection. This is also the case with the Sahrawi refugees in the Tindouf camps which is why considering Algeria alone as responsible is not very useful from the perspective of a child living in the camps. However, since not all countries recognise the SADR as a country, internationally it is usually seen as a ‘non-state actor’. This term is usually used for bodies that are not states but still relevant in the international legal community, such as international organisations like the United Nations, corporations or armed opposition groups. They cannot become a signatory to conventions like the CRC. Nevertheless, it is increasingly accepted that non-state actors should also be responsible for the rights of the people they are in control of. Legally speaking, the International Court of Justice has accepted this possibility, as long as the actor in question has ‘international legal personality’. Whether a non-state actor will fulfil this qualification, and which obligations it has if it does, depends on the actor’s purpose and function. This still sounds quite vague so to put it more concretely, here are some of the obligations that non-state actors could (or should) be bound by:

- Obligations arising out of exercising effective control over people or territories: An actor exercising government-like functions should be bound by children’s rights norms when what they do can affect the rights of the children under their control. For example, when a governing body is in control over water supply, they have to make sure that access to this water is equally accessible to all children.

- Self-imposed obligations: Many non-state actors actually voluntarily declare that they will adopt certain human and children’s rights standards. Arguably this can give rise to the actor being internationally obliged to respect these standards.

- Ius cogens norms: These are rules of international law that must be complied with at all times and cannot be derogated from, no matter by whom. The argument is that non-state actors with international legal personality should also have to follow the generally accepted rules within which they operate. Some of these rules are human rights norms, for example the prohibition of torture.

Human Rights Obligations for Polisario?

These obligations should also apply to Polisario (the Sahrawi governing body). Firstly, it has international legal personality based on its role of representing the Sahrawi people, as accepted by the UN, and secondly, it exercises actual control over the Tindouf camps and its inhabitants. This control is in many ways similar to the control a regular government usually has over a country (deciding who gets to enter, applying its own criminal and juvenile law, etc). Therefore, this almost complete control over the camps could be a reason to hold Polisario responsible for certain children’s rights obligations. This is supported by the fact that Polisario, or rather the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, the state that Polisario proclaimed, has ratified the ‘African Charter on Human and People’s Rights’, although not the ‘African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child’. It also has its own human rights catalogue included in its constitution, which contains the right to free education and the obligation to ensure protection for children. These ‘national’ or regional commitments to human rights can arguably also give rise to international obligations in the field of children’s rights.

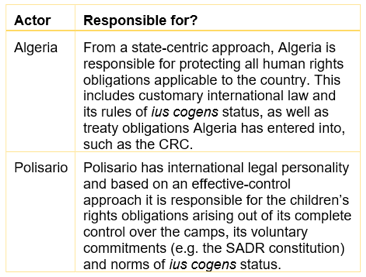

As you can see summarised in this chart, there is a lot of room for seeing Polisario responsible for certain rights of Sahrawi children, in addition to the obligations of Algeria.

Still, whether non-state actors can have children’s rights obligations remains disputed by some. Looking at the goals that international children’s rights law is supposed to achieve however, it seems like denying that Polisario can hold certain children’s rights obligations bypasses the reality of a child living in the camps and experiencing almost exclusively the governance of Polisario. Children’s rights are supposed (a) protect children and (b) apply to every child equally, independent of nationality. Consequently, if children’s rights are supposed to protect every child equally, they should also be granted to those living under the control of a non-state actor.

If you want to know more about the situation in the Tindouf camps, then follow our upcoming posts and vlogs from our field research trip!

You can read my complete thesis on this subject here.

A map of the territory of Western Sahara and the Tindouf camps.

SOURCE: Omar-Toons. (2011, 15 March). Western sahara map showing morocco and polisaro [Illustration]. Wikipedia.

Water tanks in the Tindouf camps.

In my original bachelor thesis, I also analysed the role of other actors present in the Tindouf camps. Anyone interested in reading the full version can find the complete paper here.