I am very happy to hereby share that the International Journal of Human Rights has recently published an article that present some of the findings of the case study on the child’s right to freedom of expression in Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara (MCWS). You can find the article here.

Who limits free expression for children?

The article itself is a controversial piece, since it present findings that are in some respects different from what other researchers and NGOs have published on this topic. Our findings show that, contrary to the stories (“narratives”) presented by most research and activism around human rights in the Western Sahara, the child's right to freedom of expression is limited by different groups. It is limited not only by the Moroccan state, but also by other social orders such as the community, the family and the school. Children in MCWS are not allowed to speak freely about religion, sexuality, and the Western Sahara issue. This is true for both Moroccan and Sahrawi children living in MCWS.

Dominant narratives

Children in MCWS learn from an early age that they should not discuss certain topics, to avoid violent consequences by state authorities, teachers, community-, and/or family members. You might say that a policeman is installed in the child’s mind, making the child ask ‘can I say this?’, or even ‘can I think this?’. In particular regarding the Western Sahara issue, two dominant stories (narratives) have been established, which tell children what they are and are not allowed to say or even think, about the subject. These two dominant narratives are the narrative of the Moroccan nationalists on the one hand, and of the Sahrawi activists on the other. According to the Moroccan nationalists, the Western Sahara is Moroccan territory. According to the Sahrawi activists, Morocco is illegally occupying the Western Sahara, a territory that belongs to the indigenous Sahrawi people. Sahrawi activists claim that Morocco is actively trying to eradicate the Sahrawi identity, and that Moroccan authorities are prosecuting every Sahrawi who speaks up. According to Moroccan nationalists, all people in MCWS have completely freedom of expression. The Sahrawi people can do anything they like, except engaging in violent protest.

All children growing up in MCWS, both Moroccan and Sahrawi children, have to relate to these narratives. The Moroccan narrative is taught in schools, and children are not allowed to question it. The Sahrawi narrative is taught in the homes of Sahrawi activist families, and children may not be allowed to question this either.

We also found that research and human rights activism are (unintentionally) part of the problem, because they have a tendency to present one sided stories that are in line with one of the dominant narratives.

A third narrative

However, the research also presents a hopeful message: in MCWS we found a third narrative. This third narrative tells us that while historically Morocco may or may not have had a right to take control over the Western Sahara, the fact is that Morocco rules over MCWS and has done so for a long time. Moroccan and Sahrawi children mix in everyday life on a daily basis. They go to school together, they may be friends or neighbors. Although there is no complete freedom of expression in MCWS, there is space for Sahrawi culture in Moroccan society.

This story is not heard often, because it is the story of everyday people, who do not necessarily speak up. They are not activists and they do not want to risk being prosecuted for telling their story. But it does exist. And I am hopeful that this third narrative can increasingly create space for a conversation where children are free to discuss their questions, thoughts and ideas.

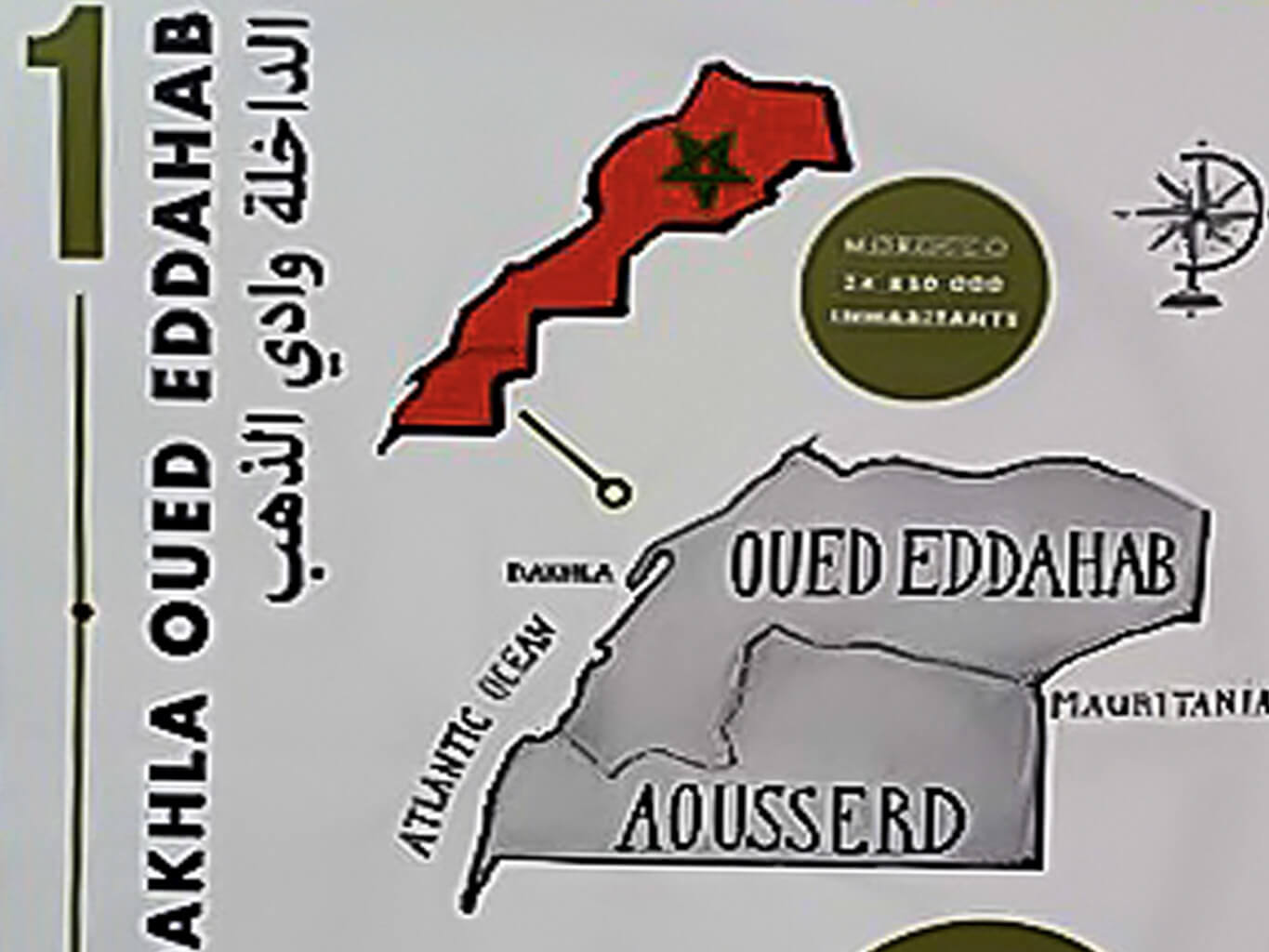

Moroccan nationalist narrative in MCWS: A tourist information board outside of Dakhla, giving information about Morocco's Southern provinces (MCWS). Notice how the map indicates ‘Mauritania’, but not the eastern area of WS controlled by the SADR government-in-exile.