It is always difficult to find reliable information on possible human rights violations in general, and in particular in areas under the control of authoritarian regimes. These areas often lack an open culture, where people feel free to speak their minds and share their thoughts with a researcher. Instead, maintaining control over information is an important task of the authoritarian regime. You may even go to jail for asking certain questions, or for giving certain answers.

As researchers, we are therefore faced with a dilemma when we want to study the rights of children who are living in such an area. In our case, we wanted to study the rights of children who live in the part of the Western Sahara that is under Moroccan control. To do so in the most objective way, we chose to use the method of “covert qualitative research” (aka undercover research). This means that you do research, you observe the subject of your research and you speak to people who can inform you about the topic, without telling anyone that you are a researcher. This is a very controversial method, because it means actively lying to people. Therefore, the method is not often used by researchers. When we started this case study, we couldn’t actually find any information on how to do this exactly. In this blog I will therefore discuss two matters:

- How to apply this method

- Whether it is ethically acceptable to use this method

For the academic journal article on which this blog is based, please click here.

How to do covert qualitative research

The first thing about covert qualitative research is that you don’t tell anyone (except your colleagues) what the true purpose is of your presence in a certain field. In our case, we travelled to Morocco and then further south to what Morocco considers its “southern provinces” (Western Sahara under Moroccan control). We travelled there as tourists and always acted as tourists.

Sampling

Choosing who to talk to (sampling) has to be aligned with the role chosen by the researcher. As tourists, it made sense for us to travel around in the area, to observe, and to speak to people in the streets on occasion. It also made sense for us to have conversations with many people in the tourism industry, such as travel guides, waiters and hotel receptionists. A problem that we encountered in our case, was that through this sampling method we included mostly men. We then tried to actively search for female research subjects, by trying to find public spaces where we might meet women. We registered for a manicure, cut our hair in a female-only hair salon, and went shopping. Unfortunately, this was only mildly successful since many women didn’t speak a language that we spoke.

Research conversations

If you don’t tell anyone you’re a researcher, it is very difficult to have conversations that provide you with useful information, but it is not impossible. This is what we learned:

- It is important to limit the number of questions you ask.

While it is normal as a tourist to be curious and interested, asking questions all the time can be suspicious or simply annoying, both resulting in you not getting too much information. We limited our questions to three categories: 1) fun questions; 2) questions on something the respondent was eager to talk about; and 3) questions relevant to the research topic (for us: children’s rights).

- Weave your questions into more casual conversation

One way to do this is to take a remark made by the respondent themself and turn this into the direction of the research topic. For example, in our experience, someone would ask ‘how do you like [name city]?’, to which we would answer with something we noticed, for example ‘I really like how everyone seems to love children! Is that right?’. A second way is to express something about your own life or experience and ask the respondent what this is like in their country. A third approach is to present an experience you have had in the country and to ask what it meant.

- When balancing between research questions and casual conversation: better to err on the side of caution

We found that if we pushed the conversation too much into the direction of the research, we ran the risk of making people feel uncomfortable or the situation getting tense. If you have to choose, better to leave the conversation lighthearted.

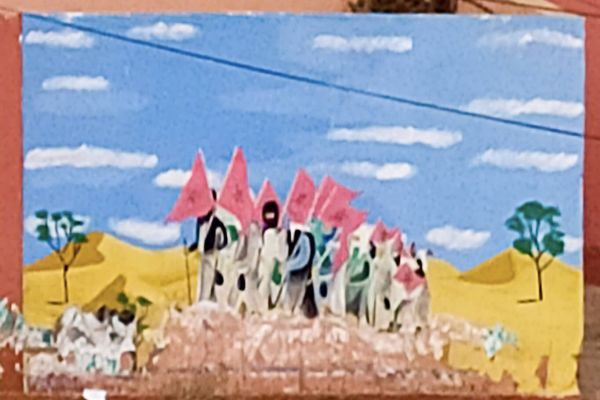

Info display on the province of Dakhla, a part of Morocco according to this information board

Data protection

In a situation where people did not choose to participate in a study, but their answers are still used as research data, the least you can do as a researcher is do your best to make sure that this information is stored safely and anonymously. For this purpose, we stored all our data in a secure cloud that could only be accessed through a particular type of VPN connection. Read more about how we did this in this paper.

Limitations of the data collected

The data you collect will most likely be very valuable, but limited. While the data is very objective (no one is trying to manipulate your research outcome since they don’t know that you are a researcher), it is also very limited. For example, you may not have access to locations you might like to study, or to certain types of respondents who are less present in the public space, and you are often not able to discuss your research subject directly. In our case, we also did online interviews with several respondents with whom we got in touch through social media after the field research.

Travelling around to observe the area

Ethical dilemmas

As mentioned above, this method comes with a lot of ethical concerns. First and foremost, is it fair not to tell people that you are actually a researcher, and to use things that they say in confidence as research data, without telling them at all? In general: of course it is not. But I believe there are exceptions. In this case, I think this method was the best one to use because:

- The aim of the research was to contribute to the protection of children’s rights.

- We were very careful to make sure that all respondents would stay anonymous.

- There was no other, more transparent way to obtain the necessary data.

Under these conditions, I believe that this type of research method is warranted, and actually it is even a good thing if in this case people go and do this kind of research. The alternative is that no research is done at all on children’s rights in authoritarian zones. Before our study, there literally was no academic study on the children’s rights situation in this part of Western Sahara. And this is mostly due to the fact that Morocco actively prohibits this type of research.

Conclusion

To conclude, I believe that covert research methods can ethically speaking be used to study the children’s rights situation of children who live in authoritarian zones. Although there are obvious disadvantages to this method, if the alternative is to have no information at all about a children’s rights situation in a certain area, I think using this method and doing research is preferred over doing nothing. From an ethical perspective, in such cases, it may even be ethically required to do this kind of research, to make sure that certain violations of children’s rights do not go unnoticed. Therefore, if there are authoritarian zones where research on children’s rights violations is not possible other than through covert research, hopefully there will be researchers willing to travel there and studying the situation as undercover researchers.

To learn about the outcome of this case study on the child’s right to freedom of expression in Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara, see this report.

Tourism activity near Dakhla: visit white sand dune